Mexico’s Superheroes: How Lucha Libre Came to Grip the United States

When the Young Bucks wrestled Pentagón and Fénix in a thrilling “Escalera De La Muerte” match on AEW’s “All Out” pay-per-view in August, the encounter was less a match and more an exclamation point on a revolution, the result of lucha libre’s impact in the United States.

The match’s most unforgettable moment occurred when masked luchador Pentagón, standing atop a ladder, flipped over Jackson, who was perched one rung below, and used his forward momentum to help Jackson backflip into position for a powerbomb. That move, known as a Canadian Destroyer, ended with a violent crash onto a table.

On first glance, it looked as though Jackson snapped his neck in half, but it was all part of the show as he was well-protected by Pentagón. There was psychology deeply embedded into the move, displaying all four wrestlers’ burning desire to win as they repeatedly risked their livelihoods to lay their hands on the titles.

“Come on, I am Penta,” said a smiling Pentagón. “Cero Miedo. There was never any doubt, never.”

The match stands in rarified air as one of the top matches so far in 2019, and stood out for its use of the lucha libre style of professional wrestling, a style of wrestling that is inherently fast-moving, colorful, and with a defined identity from its origin in Mexico. Lucha libre’s roots in Mexico date back to the middle of the 19th century, and its grip on the culture continued to grow stronger in the 1930s and ’40s. The style is replete with high-flying aerial maneuvers and colorful masks that help distinguish the wrestlers.

“When I first saw lucha, I was around 23 years old,” says Cuban-American luchador Konnan, who mastered the lucha libre style and was one of the most popular wrestlers in Mexico before a stretch in WCW where he trailed the likes of only Hulk Hogan, Kevin Nash, Sting, and Scott Hall as the most over star in WCW. “I remember seeing some lucha libre when I was a little kid, but it wasn’t real lucha libre—it was more like bringing Mexican wrestlers to the United States. But when I first really saw lucha libre, I was in the military and stationed in San Diego.

“I thought I was hallucinating, I thought I’d licked an Arizona toad. It was nothing like I’d ever seen. People were flying, they were wearing masks, the fans were rabid, and there was a lot of blood.”

Although lucha libre was perfected in Mexico, its roots have spread all over the United States, with every major promotion in the country injecting that transcendent style into their weekly shows and pay-per-views.

“In our early years, we started out learning the art of lucha libre, so we knew that pairing us with luchadores is always going to be good,” said the Young Bucks’ Matt Jackson, who also booked a six-man, lucha libre match to main event the groundbreaking “All In” show a year ago. “Lucha libre style is so easily digestible because it’s crisp and quick.”

Mexican lucha promotions are also making inroads in the United States. Led by its president, Dorian Roldán, the Mexico-based Lucha Libre AAA Worldwide promotion ran a show in the Hulu Theater of the famed Madison Square Garden on Sunday, the first day of Hispanic Heritage Month. Another show in Los Angeles is slated for October.

“In Mexico, we don’t have superheroes,” said Roldán. “We don’t have nothing like that—we have lucha libre and luchadores are the Mexican Marvel. Lucha libre is Marvel in Mexico. There are good guys and bad guys in this universe with storylines that all happen in the ring.”

AAA’s New York show featured some of the most exquisite lucha in the world, including Pentagón, Fénix, Taya Valkyrie, and the second match ever for masked luchador Cain Velasquez, who is a former UFC Heavyweight champ and, you may recall, knocked out WWE’s Brock Lesnar in the Octagon.

“Lucha connects to my childhood,” said Velasquez. “Every time I pictured myself doing this, especially recently, it was with the mask and through lucha. That’s the influence of the culture and tradition on me, and that’s why I’m doing it this way.”

Women have also mastered the lucha style, none better than Taya Valkyrie, now a three-time AAA Reina de Reinas (“Queen of Queens”) champion after defeating Tessa Blanchard for the title in New York. She has spent the past seven years perfecting the craft of lucha, beginning her training in 2012 under the legendary Silver King on the fourth floor of a boxing gym in Mexico City.

“My entire life I’ve had challenges put in front of me, and I pride myself on changing the way people think about something,” said Valkyrie. “I’m a blonde, Canadian girl that went to Mexico, but I was motivated to show that lucha libre is multicultural and can break borders across countries.

“Lucha is an art form of passion, and there’s so much more than just wearing a mask and doing a crazy flip to the outside. Lucha is that fighting spirit, pushing the limits of your physical ability while creating emotion, and being true to the tradition of the art form. That’s what makes me a luchador, not dropping a 630 senton. Being at the Garden on Sunday was a testament to that and shows we are worthy of this attention.”

Long a part of the cultural fabric in Mexico, lucha’s popularity has continued to grow in the United States over the past two-and-a-half decades. Like most revolutionary concepts in the business of professional wrestling, it should hardly be surprising that the rise of lucha libre in the United States has one man’s fingerprints all over it.

That one man is Paul Heyman, the John Lennon of the U.S. lucha invasion.

“Paul Heyman is brilliant, I can’t say that enough,” said Konnan, who is the godfather of lucha in the U.S. “And he was brilliant when it came to luchadores and lucha libre.”

Konnan dates the birth of lucha libre in the US to 1993 when Heyman—Paul E. Dangerously on TV and just Paul E. to his friends—was in Manila. Across from him was Charles Ashenoff, known to the wrestling world as Konnan.

Heyman’s mind was percolating with ideas for a soon-to-be extreme, industry-defining promotion.

“Paul E. had just taken over in ECW, and he was like, ‘Hey man, Eddie Guerrero and Love Machine, they’re tearing it up,’” said Konnan. “He wanted to bring them to ECW.”

Heyman was in the process of putting together a concept that would eventually be labeled “extreme” and forever redefine the wrestling world. His mind drifted in the conversation with Konnan, with visions of a progressive, never-before-seen tag team to be a centerpiece of his new promotion. The team he had in mind was Love Machine (Art Barr) and Eddie Guerrero, who captured Heyman’s imagination, attention, and wallet with their work together in Mexico as Los Gringos Locos.

Heyman planned to bring in Barr and Guerrero to challenge Public Enemy, the standard bearer for tag team wrestling in ECW, but Barr passed away before it could happen. He was only 28.

“After Art died, Paul said to me, ‘I keep hearing about Rey Mysterio,’” Konnan recalled. “Everybody back then had been saying, and I mean everybody was saying this—Rey was too small. But Paul never brought up Rey’s size.

“So Paul says, ‘I keep hearing about Rey Mysterio and Psicosis. What can you tell me about them?’

“I told Paul, with all due respect to the rest of your roster, they’re going to tear s--- up and people are going to love them.”

Konnan proved prescient. A 20-year-old Mysterio and 23-year-old Psicosis made their famed ECW debut against one another at the “Gangstas Paradise” show in September 1995. They showed how lucha libre was inherently fast-moving, colorful, and carried authenticity with an already defined identity from Mexico.

The psychology and selling in their match made sense, and Mysterio’s springboard plancha into the second row of the crowd was a sight to behold. Suddenly, lucha libre had more genuine respect and appreciation than ever before in the U.S. The style fit culturally into a society where everything was becoming faster, with nonstop movement and motion.

From that point forward, lucha libre would begin to play a role in WCW, WWE, and independent promotions all throughout the United States—but, as Mysterio explained, the process took time.

“My size was an issue when I first crossed the border and started performing,” said the 5'4" Mysterio. “There was no size differential in ECW. Their fans were very open-minded. As long as you performed well in that ring, they didn’t care if you were short, had one leg, or one arm. If you could perform, they were going to applaud and want you to come back.

“WCW was different. The slang was, ‘WCW is where the big boys play.’ I was never confused with a big boy.”

Mysterio’s WCW debut took place in June 1996 against Dean Malenko at the Great American Bash pay-per-view.

“I thought it was going to be a dark match, but this was live on pay-per-view,” said Mysterio. “Malenko was someone I’d never wrestled before, I’d never even met him. No pressure, right?

“The company didn’t know if I could deliver or not, and they were counting on what they’d seen on tapes and word of mouth—my entrance into WCW was thanks to Konnan.”

Mysterio and Malenko, aptly nicknamed “The Man of 1,000 Holds,” were nothing short of spectacular.

Complemented by the commentary of lucha expert Mike Tenay, a new form of pro wrestling poetry was being written on the WCW canvas. The match included the traditional aspect of working on a body part, as Malenko constantly attacked the left arm, shoulder, and elbow of Mysterio. Viewers were captivated by the upside-down surfboard (“La Tapatia”), listening as Tenay explained the origins of the move in Mexico. The match was brought to new heights when Mysterio hit a springboard somersault off the top rope and crashed onto Malenko outside the ring. This took place only after “The Man of 1,000 Holds” had worked unrelentingly on the mat to hyperextend Mysterio’s elbow, and the psychology behind making people wait—and wait and wait—for the aerial assault was perfectly executed.

Finally, Malenko powerbombed Mysterio and got the pin by using his feet on the middle ropes for the extra leverage required to hold down the relentless luchador.

“I went out there and connected with Dean Malenko,” said Mysterio. “And something new and exciting just began that night.”

The way in which lucha libre, with its fabric sewn so deeply into Mexican culture, has become so popular in America is striking, especially when considering WWE has played only a minor role in its growth. The world’s largest wrestling promotion has largely steered clear of the styles, and struggled to produce authentic lucha libre when it has attempted to.

“There’s a reason for that,” explained Konnan. “The establishment didn’t understand it and they didn’t grow up on it. When I got to WWE and was doing the Max Moon character, Vince McMahon never said, ‘What can we do for the Latino demographic? Can we get lucha here?’ He just wanted to get the Max Moon robot, which was a pretty cool concept, off the ground. Lucha wasn’t accepted by the establishment, but the fans have always loved it.”

WWE’s primary ’90s competitor, WCW, embraced the stateside growth of the lucha style, though. It produced the When Worlds Collide show that brought lucha stars to pay-per-view in 1994, but despite the enormous popularity evidenced by the crowd at the show in Los Angeles, the lucha scene in the U.S. did not change until Heyman brought the style to ECW a year later. That formula was then copied on a substantially larger platform by WCW president Eric Bischoff with the debut of Monday Nitro in 1995.

“My original goal when we launched Nitro was to make it more international, so lucha libre was a big part of that goal,” said Bischoff, who is now WWE’s Executive Vice President overseeing SmackDown Live. “I knew at the time it was a different style of wrestling, and wrestling fans are interested in seeing a variety and a diverse presentation of the product.”

Konnan signed with WCW in 1996 and, with behind-the-scenes help from “The Taskmaster” Kevin Sullivan, brought along a number of luchadores with him.

Bischoff bolstered his cruiserweight division on Nitro with the likes of Mysterio, Psicosis, Juventud Guerrera, Eddie Guerrero, Chris Benoit, and Dean Malenko.

“We had such a great group,” said Kevin Nash, who starred on-screen in WCW and served as a big advocate off-camera for lucha. “Malenko, Eddie, Benoit, Jericho, and Rey Mysterio were in that group. I mean the guys who opened the show were arguably five-to-ten Hall of Famers.”

WCW broadcasts did not always treat the luchadores with the same legitimacy as more established stars, but the promotion did provide an opportunity to significantly raise the profile of lucha libre, especially during the first hour of Nitro, renowned among fans for matches featuring luchadores.

The decision to include luchadores on WCW programming, Bischoff explained, was to embed a much different feel into the product than the WWE’s presentation, which, at the time, was often more cartoon than competition.

“A lot of the lucha characters are very colorful, the action is outstanding, and that’s why we exposed lucha on the national stage in WCW,” said Bischoff. “Others had promoted lucha in the United States, certainly in California, and Paul E. Dangerously in ECW, but those were smaller platforms.

“I jumped on that bandwagon, and giving lucha a national platform and exposing it to a mass audience was instrumental in the beginning of exposing lucha.”

The evolution of lucha libre mirrors the growth of pro wrestling in the US, as both remain pillars of a continual evolution.

“Wrestling is popular all over the world, and I’m happy to see that lucha libre is even more popular now in the US,” said Bischoff. “I’m not surprised by that, I’m encouraged. It is another layer of entertainment and culture that wrestling fans can enjoy.”

Some also see the growth of lucha as a natural occurrence for an entertaining product. Jim Ross, who is the voice of wrestling and currently working as a senior advisor for AEW, believes it was only a matter of time before lucha’s reach extended deeper into the US.

“Lucha libre is part of the fabric of the wrestling culture, so I’m not surprised it’s growing in the United States,” said Ross. “It’s been around for a long, long time—AAA started in 1992 and CMLL, another promotion in Mexico, started in 1933, and that’s even before WWE—so it was only a matter of time before it became more popular in the States.”

While it could be argued that lucha libre is not intertwined with American culture, Ross views the topic from a different perspective.

“There is a huge Latino audience in wrestling, some of whom have lucha libre as part of their heritage with grandparents who remember the great wrestling star El Santo being a movie star in Mexico,” said Ross. “And here’s the thing, you need to credit the talent. The luchadores are amazing. I remember how extraordinary I thought it was to see Rey Mysterio for the first time, or Chavo Guerrero’s moonsault, then came Eddie. Nowadays, you can be blown away by the Young Bucks or Pentagón or Fénix.”

Leave it to Konnan to find the connective tissue between lucha libre, the United States, and hip-hop.

“Lucha libre reminds me a lot of hip-hop,” said Konnan. “When I was growing up in Miami, hip-hop was mostly performed by blacks and Latinos. It was basically a hood thing that came from the South Bronx. Miami, as you can imagine, had a s---load of New Yorkers down there for the winter, so we were very influenced by New York.

“Now fast forward to today. The best-selling rapper is a white guy. Hip-hop is now a global phenomenon that’s taken over the pop charts. And the same thing has happened with lucha.

“When lucha started, everyone was Mexican. Now fast-forward 25 years, and you have it in every nationality. It’s in England, Japan, Germany, with different cultures and different races. Just like hip-hop started black and Latino, lucha libre started Mexican, but they both exploded and became a phenomenon everyone could embrace.”

South African luchador Angélico (standing) and his American tag team partner Jack Evans.

James Musselwhite/All Elite Wrestling

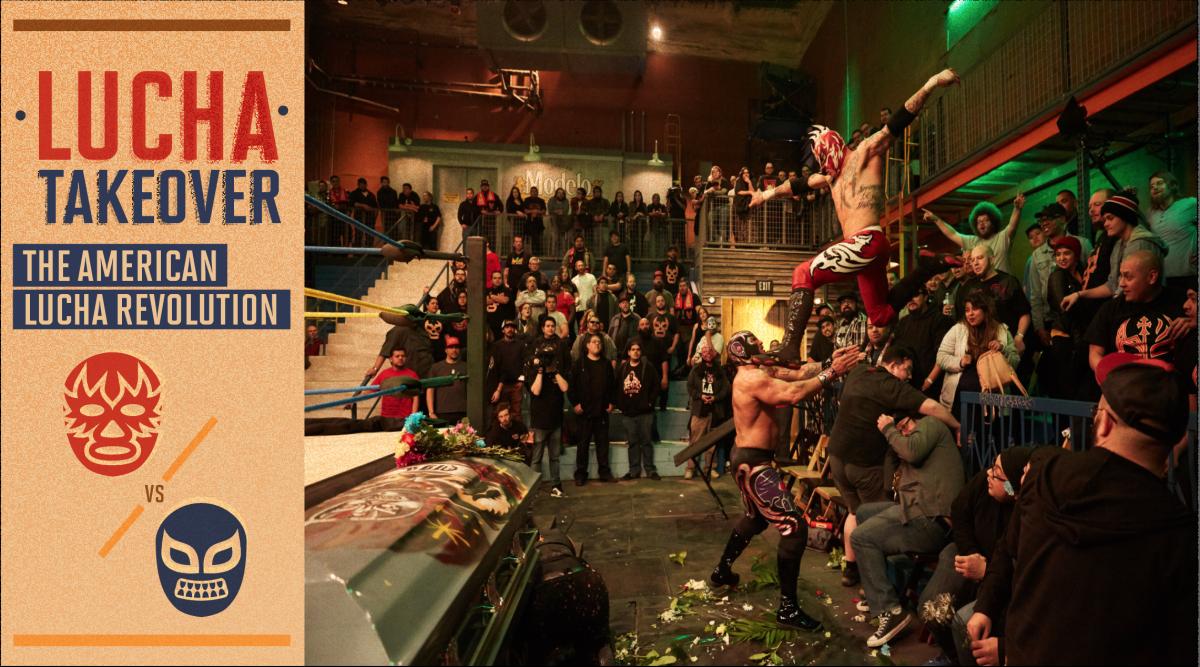

New companies continue to find ways to introduce lucha-style wrestling to American audiences. The Lucha Underground TV series that premiered in October 2014 on the El Rey Network was the first American television show that used lucha as more of a main course than an appetizer. More than just wrestlers wearing masks, it had a mythology, was episodic, and played to the strengths of characters with vibrant personalities and looks. The series, which heavily featured supernatural elements and science fiction, found a wider audience when it began streaming on Netflix in 2017 and brought top-tier luchadores like Pentagón and Fénix wider acclaim.

El Hijo de Fantasma, a luchador who lost his mask at AAA’s TripleMania show last summer, starred on Lucha Undergroundas King Cuerno. He believes lucha has reached a new level of popularity because of what was accomplished through Lucha Underground.

“The main reason why lucha is very popular is due to the work of what I like to call the ‘Lucha Originals’ from Lucha Underground,” he said. “That’s myself, Pentagón, Fénix, Drago, Mil Muertes, and Sexy Star. Since then, people have continued to like and do what we started on Lucha Underground.”

Though not historically its strongest attribute, WWE’s role in promoting lucha libre is also important. The company’s most popular luchador, Mysterio, who remains incredible in the ring even at age 44, returned to WWE in 2018 and now works in tandem with Heyman again on Raw. Last week, he wrestled a fantastic match against fellow masked luchador Gran Metalik.

The company also employs lucha standouts Andrade and Ricochet, who performed under a mask on Lucha Underground as Prince Puma. El Hijo de Fantasma recently signed a developmental contract with WWE to work at the company’s Performance Center in Florida.

“There is still a lot to be done,” said El Hijo de Fantasma. “We captured the attention of the American audience, but we still have to educate them on some aspects of lucha libre, like the meaning of the mask, Mexican wrestling psychology, and the tradition and the culture of lucha libre in Mexico.”

The meaning of the mask is of tremendous importance in lucha libre. It doesn’t just identify the performer, it is their identity. The real name of the person behind the mask is usually not public knowledge. Vince McMahon, better than anyone in the US, brilliantly marketed Mysterio’s mask to his fan base.

“The genius of Vince was putting the mask back on Rey after he lost it in WCW and he made millions off his mask,” said Konnan. “Even though Vince has never really been able to promote lucha libre correctly, he did promote Rey the right way.”

Creative, flashy, and colorful, lucha has added another element of substance and entertainment to the pro wrestling scene in America. As for where lucha libre goes next, there remains plenty of opportunity.

“Lucha libre is so popular in the United States, that’s why I’m speaking English,” explained Fénix, who burst on the scene in the U.S. with his 2015 casket match against Mil Muertes on Lucha Underground. “When I was 13, 14, I never thought I’d learn to speak English. To be involved in so many shows in America, and make me so much bigger, and it makes me work harder every day.”

Promotions throughout the US are incorporating and embedding lucha libre into its product in ways that wrestling fans in the states have never before seen.

The style is now an indispensable part of the wrestling scene. Wrestling, as evidenced by AEW, showed that the business is in the hands of the fans. Promotions are listening to fans in ways previously unimaginable. Fans are no longer beholden to the establishment.

And with the voice of the fans stronger than ever, lucha libre will continue to widen its reach in America.

“People used to think lucha was just a bunch of flippy s---,” said Konnan. “But what it’s done is open everyone’s eyes. Lucha brings a really festive atmosphere. And it’s amazing, this really cool way of wrestling from Mexico has now made it in the United States—and best of all, the people love it.”

Justin Barrasso can be reached at JBarrasso@gmail.com. Follow him on Twitter @JustinBarrasso.