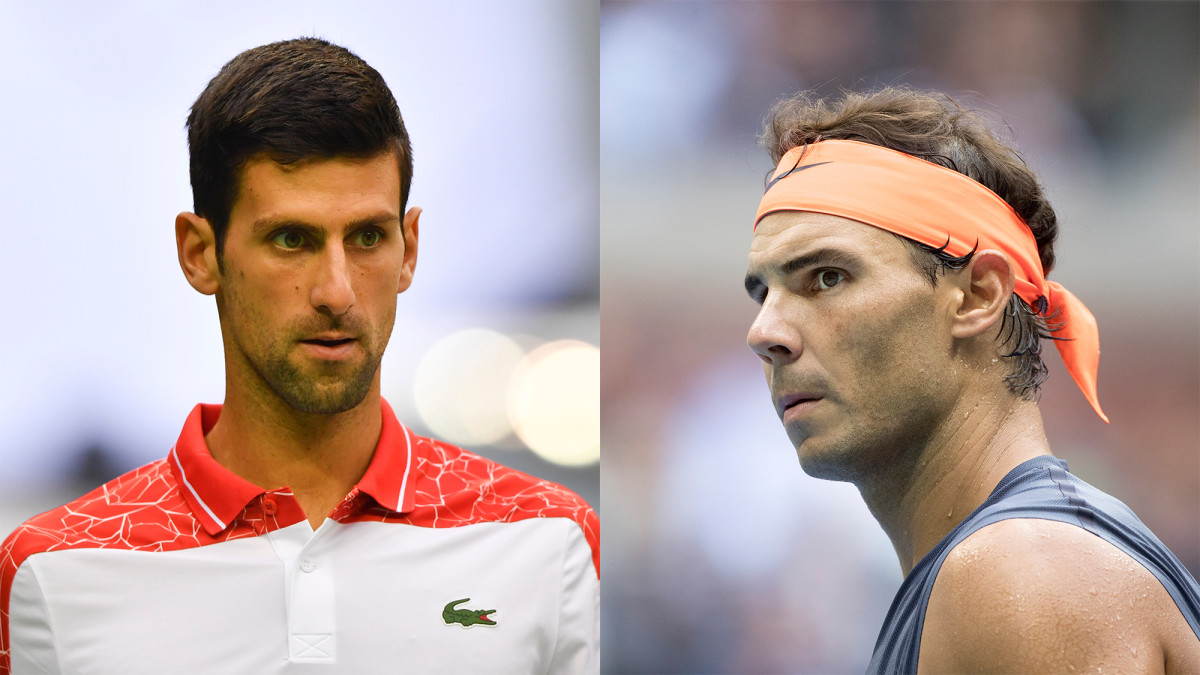

Djokovic, Nadal Should Reconsider Exhibition in Saudi Arabia After Jamal Khashoggi's Killing

One day after the alleged murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi first came to light, Saudi Arabia's sports minister announced a tennis exhibition in Jeddah on Dec. 22 between Novak Djokovic and Rafael Nadal. The uncanny timing was perhaps coincidental. But the connection between the two events—the killing of a dissident journalist and a planned exhibition between the ATP’s top two players—can not be ignored.

Here’s what we know about the basics facts of Khashoggi’s death, which the Saudi government finally acknowledged on Friday: On Oct. 2, Khashoggi entered the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. He was killed inside the building by Saudi officials, who claim he accidentally died after a fistfight. But American intelligence has rejected the credibility of that explanation, and the Turkish government says it has audio indicating Khashoggi—a Saudi national living in self-imposed exile in Virginia—was tortured and dismembered in the consulate within minutes of his arrival.

So how does Khashoggi’s killing relate to a tennis match? It’s all about the image Saudi Arabia wants to project to the rest of the world. In late 2016, as Karim Zidan chronicled for Deadspin earlier this year, the government created a Sports Development Fund urging “an infusion of capital to build new facilities, contributions to the privatization of sports clubs, and efforts to attract and promote international sports events”—hence December’s tennis match. Additionally, staging major sporting events also builds Saudi Arabia’s international stature and helps obscure human rights violations.

It’s part of a broader modernization effort known as Vision 2030, a plan conceived by Mohammed bin Salman, known colloquially as MBS, the 33-year-old crown prince of Saudi Arabia and the kingdom’s de facto leader. Despite the fact that bin Salman consolidated power by detaining scores of Saudi princes and businessmen on spotty corruption charges—some detainees were reportedly tortured—he was lauded last year by the Thomas Friedmans of the world for his purported agenda of reform, which entails transforming the country socially and economically. But with the clarity of hindsight, the initial heralding of MBS appears increasingly naive, especially since Khashoggi’s death. Bin Salman is tied to multiple suspects in the alleged murder.

Khashoggi’s death ignited a genuine political crisis for Saudi Arabia by spotlighting the regime’s brutality. But the Saudi government’s investment in athletics—from tennis to WWE to soccer—is a strategic endeavor aimed at cultivating a more palatable external face. And the participation of Djokovic and Nadal in a Saudi-funded event is a public relations coup for a repressive government finally facing some scrutiny over its poor human rights record, which encompasses far more than the Khashoggi ordeal.

Most notably, in Yemen, Saudi Arabia's intervention in a civil war has worsened what United Nations officials call “the worst man-made humanitarian crisis of our time.” A Saudi-led coalition, using American weapons, has repeatedly targeted civilians with airstrikes, killing thousands. And within Saudi Arabia, even after modest reforms, women are treated as second-class citizens. Freedom House rates Saudi Arabia as one of the least-free countries in the world.

Yes, plenty of countries governed by autocratic or authoritarian regimes host tennis events. But in this case, the government is directly sponsoring the exhibition. The match—the King Salman Tennis Championship—is quite literally named after the country’s monarch.

While Djokovic and Nadal might prefer to cash their (surely generous) participation checks and avoid the political fray, they have an opportunity to use their platform for good. They could pull out of the exhibition, just as several companies and chief executives recently withdrew from an upcoming Saudi-hosted business conference in response to Khashoggi’s death. They could also offer their support—financial, vocal or otherwise—for basic human rights, as Amnesty International suggests.

“It’s not for us to say which countries should and shouldn’t be hosting sporting competitions, but it’s also clear that countries like Saudi Arabia are well aware of the potential for sport to subtly ‘rebrand’ a country,” Amnesty International’s Allan Hogarth told the Sunday Times. “It’s up to Nadal and Djokovic where they play their lucrative exhibition matches, but if they go to Jeddah we’d like to see them using their profiles to raise human rights issues. Tweeting support for Saudi Arabia’s brave human rights defenders would be a start.”

So far, at least, Djokovic and Nadal have remained quiet. But as Khashoggi himself demonstrated, even posthumously, silence shouldn’t be an option.