Remember The Ringleader

“Raus, raus! Alles lassen liggen!”

On a snowy Sunday in January, 76 years ago, a Nazi freight locomotive emptied 659 Dutch Jews—240 men and boys, 419 women and girls—onto Auschwitz’s train platform following a 36-hour trek east from the Dutch city of Westerbork. The SS guards shouted again: “Out, out! Leave everything behind!”

Leon Greenman, slim and 32 back then, would decades later recall noticing the corners of suitcases jutting from hard-packed snow drifts near the tracks. He wondered: Why did those people leave their belongings? Here were the cases, but where were the people? Surely, he figured, he would be invited back later to retrieve the hastily-packed bags that he and his wife had brought.

“Männer zur linken! Frauen nach rechts!” (Men to the left! Women to the right!)

Among those shuffling off the train that day with Greenman was Eddy Hamel, who not long ago had been one of the best soccer players in the world. Now 40, Hamel didn’t stand out much from the other Auschwitz arrivals. His fit build was hidden by an overcoat dirtied on a frigid train ride with no food, water or toilets.

Born in New York City in 1902, Hamel had moved to the Netherlands as a baby, with his Dutch-born parents, and considered himself more Dutchman than Yank. During World War II, many Jews who could prove American or English citizenship were sent by the Germans to one of the less severe Nazi camps, where they might be traded for German POWs. When Hamel had been arrested in Amsterdam three months before arriving at Auschwitz he’d told his captors about his American roots. He was unable, though, to prove this claim to U.S. protection, and so there he stood, at the gate of the most murderous concentration camp of them all, separated by armed soldiers from his wife, Johanna, and their twin 4-year-old sons, Paul and Robert.

Survivors and historians tell us that the prisoners who arrived at Auschwitz before 1944 didn’t know what awaited them—didn’t know about the thousands of murders that took place there every week. They’d been told they were being sent to work. Greenman got a glimpse of reality fast. A woman, he recalled, ran across the platform toward her husband, but halfway there was clubbed to the ground and kicked in the stomach.

Out of these 659 souls, 19 women and 50 men—Hamel and Greenman included—were selected for a work assignment. They were led away, past gardens intended to make them believe everything would be fine, while the 590 others, including Hamel’s and Greenman’s families, were shepherded elsewhere.

Auschwitz was not one place but a complex of sprawling camps where between 1940 and ’45 death was secretly administered by bullet, poisonous injection, medical experiment, beating, overwork and malnutrition. The vast majority of the 1.1 million to 1.5 million people estimated to have been murdered at Auschwitz, however, were executed by poisonous gas spread through holes in the ceilings of what prisoners believed to be shower rooms.

Eddy Hamel, former star winger for Ajax, the finest football club in Holland, knew none of this. The world didn’t know this. The rare prisoners who caught sight of these truths tried to tell the others. They pointed toward the smoke and the smell, but most inmates simply didn’t believe the Germans were gassing people by the thousands and turning the corpses to powder.

“To believe such a thing,” said one Auschwitz survivor, “you had to cease being human.”

The fact that Eddy Hamel was born on Manhattan’s Upper East Side—in his parents’ apartment at 503 E. 83rd St.—meant little until his life depended on it. And even then, it couldn’t save him. Not without proof.

Moses and Eva Hamel had moved to New York from Holland the year before Eddy was born. A diamond polisher by trade, Moses must have found work hard to come by in the town known as New Amsterdam before the invading Brits renamed it in 1664. Six months after Eddy arrived, the Hamels returned to Old Amsterdam for good.

Another native New Yorker, Jim McGough, sat explaining all of this in the corner of a restaurant in Pleasant Hill, Calif., recently. A fit, 54-year-old tech executive, McGough got his first taste of European soccer when he traveled to Amsterdam and visited a Dutch friend in the early 1990s. The Ajax match he caught during that trip was a life-changer. Upon returning to the States, McGough created a website (a strange new endeavor at the time) called ajax-usa.com, which attracted a worldwide following of soccerheads. Hamel became a particular fascination of McGough’s, and over the past 15 years he has made it his mission to learn as much as he can about the Hamel story, which the sands of time had slowly concealed, grain by grain, until an 87-year-old Auschwitz survivor unearthed it in 1998.

McGough has traveled several times to the Netherlands in pursuit of anyone who still remembers Hamel’s name, and he’s dug up dozens of aging documents, like the guest columns Hamel wrote for the clubs he coached after his playing days. In one of those, from 1933, Hamel recalled that “the first real soccer match I saw as a young rascal was played on the dirt field of A.F.C.” That would be the lower-tier Amsterdamsche Football Club, which Hamel later joined, becoming a fixture on its top team as a teenager.

It was McGough, along with Dutch journalist Menno Pot, who translated the 2003 book Ajax, the Dutch, the War (by Simon Kuper), including a story about a teenage Hamel mischievously kicking balls at the windows of the Ajax facility. This misbehavior was curtailed when a groundsman got his mitts on the young A.F.C. player and plunged Hamel into a nearby stream.

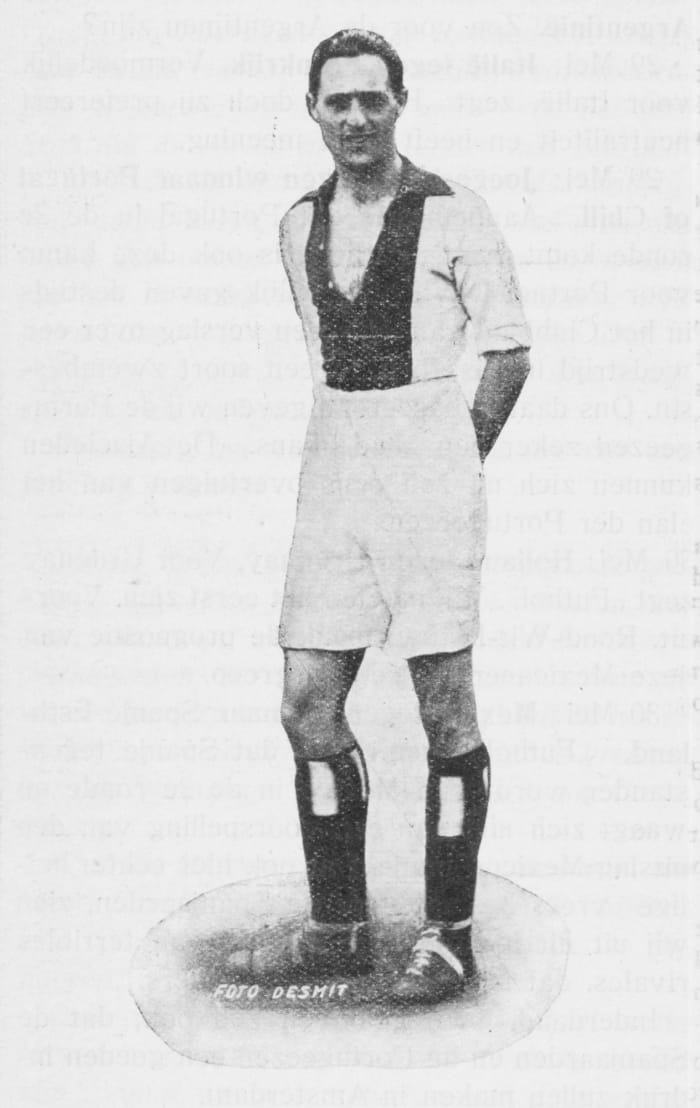

Soon enough that groundsman would be a colleague, for in 1922 Hamel, 21, joined what Kuper calls the Netherlands’ “biggest football club and probably the country’s most popular institution after the royal family.” The first American-born player to compete in a top-flight European league, according to the National Soccer Hall of Fame, Hamel played 125 games at right forward for Ajax over the next nine years, the locals heralding him as Belhamel, or The Ringleader. He was known for his speed, his dribbles down the right flank and for the crossing passes that helped fill the goals at Het Houten Stadion, the Wooden Stadium. Those grounds in Amsterdam held only 11,000 people, but on certain Sundays the throng swelled to 20,000, with fans’ toes covering the sidelines. Hamel himself had a legion of supporters who switched sides at halftime to better witness his offensive exploits.

Twenty-odd years ago Kuper tracked down an elderly Ajax supporter, Hans Reiss, who described a “tall boy, black hair combed back. Not a product of the Jewish Quarter. He was what you might call an idol. Eddy Hamel, I can still see him before me. Quick, and he had a very good cross. Something like David Beckham now.”

Except that Beckham scored goals, and goals weren’t Hamel’s thing. He scored just eight in his career. His appeal, instead, was in his playmaking and his manner.

“Gé van Dijk, an Ajax star in the 1940s and ’50s, used to go and watch Hamel with his friends, when [van Dijk] was still a junior player himself,” journalist Arthur de Boer wrote in 2000, on the occasion of the club’s centennial. “‘[Hamel] was a wonderful footballer,’ [Van Dijk said]. ‘An icon. And what I liked the most about him: He was always such a gentleman. He never kicked opponents or things like that. He was my role model. I never kicked anyone myself. I wanted to be like Eddy Hamel.’”

For more than a century Ajax has had a strong Jewish identity, not because of Hamel, the first Jew to play for them (and one of only five in the team’s history), but because of the Wooden Stadium’s proximity to Jodenbuurt—Amsterdam’s Jewish Quarter. In Hamel’s day, and even before, lower-middle-class Jews formed the bulk of Ajax’s fanbase. That association still lingers today. At the team’s Champions League match against Real Madrid on Wednesday, Ajax supporters who aren’t the slightest bit Jewish will file into Johan Cruyff Arena waving flags and bearing tattoos that depict the Star of David, chanting the Dutch word for “Jews”: YO-den! YO-den! It’s a tradition that has withstood the hissing sounds made by opposing fans (to mimic the gas chambers) and that has defied pleas from Ajax’s front office to leave the Jewish paraphernalia at home, so as not to provoke trouble.

Hamel’s Jewish heritage is irrelevant to his soccer career, other than the retroactive sense of foreboding it provides today, for his playing days ran concurrent with Adolf Hitler’s rise to power. Hamel scored a career-best five goals in the 1926–27 season (and over the years helped guide de Godenzonen to four division titles) while Hitler, chairman of the fledgling Nazi party, was seizing upon Germans’ rising frustrations by promising economic renewal and revenge against the religious group he held responsible for the country’s downturn.

In August ’29, Hamel married Johanna in an Amsterdam synagogue; a year later he assisted on Ajax’s first goal in a 6-0 win over Koninklijke HFC ... and then wrecked his knee. He never again played for the storied club’s A squad.

For all of his successes on the field, Hamel received no money—European clubs back then were truly clubs; players wouldn’t be paid until the 1950s—so he returned to his day job as a clerk at a grain wholesaler. In ’32 he began coaching two lower-level clubs: one in the fishing village of Volendam, just outside Amsterdam; the other further north, in Alkmaar. In ’33 Adolf Hitler ascended to chancellor of Germany and opened his first concentration camp, in Dachau; five years later, Johanna Hamel gave birth to Paul and Robert. Hamel was coaching three teams by this point and being compensated for it, however modestly. Volendam sometimes paid him in fish.

“I have this wonderful invented image of him,” says McGough, the one-man Hamel museum, who has retraced the steps Hamel took after getting off work at the grain shop and riding various trains to the three scattered clubs he oversaw. “It’s night, and he’s riding home, holding a basket of eels, or herring, stinking up the whole train.

“Clearly he was a good coach. Alkmaar won the league title when he was there. He coached de Kennemers [also near Amsterdam] to a championship and got them promoted. Volendam, which had never won anything, won three league titles in the 10 years he was there. The old timers in Volendam still talk about Eddy Hamel as ‘the guy who changed everything for us.’”

World War II began on Sept. 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland. Eight months later, Germany took the Netherlands—but the atmosphere in Amsterdam had grown tense before that. Despite its robust Jewish populace, a vein of anti-Semitism ran through the city of 800,000, as it had through all of Europe since the Middle Ages. Among the many restrictions placed by the Nazis on Amsterdam’s Jews was their banishment from sporting clubs. Hamel was no longer allowed to coach. Soon the Jewish Quarter—the soil from which Ajax’s following had sprouted—would become a ghetto, sealed in barbed wire.

Hamel, his wife and their sons were living across town at the time, in a second-floor flat at 145 Rijnstraat, not far from where 13-year-old Anne Frank and her family lived. In apparent defiance of the Nazis’ rules, Hamel continued to play for his old club’s alumni team, Lucky Ajax, during the German occupation.

On Oct. 27, 1942, Hamel was stopped by two officers from the Jewish Affairs division of the Amsterdam Police Department, which had turned compliant with the Nazis. The arrest report, written in German, states that Hamel told his captors he was born in New York. He gave “coach” as his profession. As for the reason for his arrest: He’d been caught in public sich ohne judenstern—without his Jewish star.

“Why wasn’t he wearing a star?” McGough wonders. “Also, did someone tip off the Nazis? There are some fascinating mysteries in this.”

After Johanna and Paul and Robert were rounded up, the Hamels were taken to a beautiful edifice downtown, the Hollandsche Schouwburg Theater, which had been turned into a detention center, and then to Westerbork, a Nazi transit camp 100 miles northeast of Amsterdam.

“Westerbork was designed to project calmness,” says McGough. “The Germans wanted to keep prisoners pacified until they went to die.”

Westerbork had a cabaret theater, a good hospital, an orchestra and, McGough adds, “organized soccer. The prisoners played two pickup games every Sunday, at noon and 3 p.m.” During the three months Hamel was there, “it’s hard to imagine he didn’t at least kick the ball around.”

Westerbork is where Hamel met Leon Greenman, a London-born bookseller who’d been arrested in Rotterdam. Decades later, Greenman would write in his memoir, An Englishman in Auschwitz, of his desperate quest to prove he was a British subject. The necessary documents arrived in Westerbork in late January of 1943—but they were too late. Greenman, his wife and their 2-year-old son were already on an Auschwitz-bound train.

“We had been told that we were being sent to Poland to work for the Germans,” Greenman wrote of his family’s journey. “We thought that we would ... be allowed to visit one another at weekends.”

Greenman kept his memories of Hamel to himself for more than 50 years, until 1998, when he mentioned to a fellow Auschwitz survivor that he’d met an Ajax player named Eddy Hamel inside the infamous death camp. The man responded: “You should tell Ajax about that.” And so Greenman did, in a letter that concluded, “Apologies that these facts were not forthcoming, not everybody is interested in what once was. Yet I hope to have done something good out of respect for Eddy Hamel and your mighty football club.”

Greenman is our best window into Hamel’s experience at Auschwitz, for not only did the Germans burn bodies and scatter ashes, they also destroyed many records of the genocide after the war turned against them in 1944. From Greenman’s book, published in 2001, we know that he and Hamel had not eaten in three days when they arrived at Auschwitz. Their first meal was “some kind of herb soup with black-coloured leaves.” In the weeks that followed they subsisted on the occasional scrap of bread or raw potato, in portions that were reduced daily. Water was their greatest nutritional deficit.

In a barrack filled with 1,000 men, Greenman and Hamel shared a wooden bunk—the highest of three, with no mattress. (Intended for one man, each of these three levels instead held eight.) That February and March in 1943, with an average temperature hovering around 30, “Eddy and I often rubbed our backs against each other,” Greenman wrote. “His body was very warm, you see. And we were very cold.” Speaking Dutch, “mingled with the odd word of English,” Hamel told Greenman he was an American citizen, and Greenman explained his London roots. They agreed not to talk about the women and children who had accompanied them on the train. “We saw the smoking chimneys, heard the tales about the crematoria,” Greenman wrote, “but we convinced ourselves that they were just factories.”

The men performed hard labor in the snow, in accordance with the wrought-iron sign that arched over Auschwitz’s entrance: ARBEIT MACHT FREI, or WORK SETS YOU FREE—yet another bit of propaganda. Three months passed. An Austrian prisoner reluctantly tattooed 98288 on Greenman’s left forearm. The Nazis probably gave Hamel, the man behind Greenman alphabetically, number 98289.

“Our conditions were turning some of us into different people,” Greenman wrote. “Not all of us—some remained almost the same as when they arrived. Eddie [sic] Hamel was always a gentlemen [sic].”

Kuper recounts the ways in which Hamel may have been unlucky in landing at Auschwitz. If he’d shown a passport or some other proof of his American roots, might he have been sent elsewhere? If he’d been more widely-known, as today’s players are, or scored more goals or played for Ajax more recently, would someone have recognized him and supported his story about being born in New York? Or would a degree of fame have been inconsequential? In Who Betrayed the Jews? Agnes Grunwald-Spier writes of “more than 30 Jewish Olympic medalists [who] were exterminated without a thought when the Nazi juggernaut ploughed on with the Final Solution.”

Three months after arriving, Hamel and the other men in his barracks were led to a room and ordered to strip naked. As they stepped forward one by one and were directed to either the left or right, it became clear what was happening. The healthy would be allowed to keep working. The unfit would not. According to Greenman: “[Eddy] said to me, ‘Leon, what is going to happen to me? I have an abscess in my mouth.’ I took a look. It looked swollen indeed.

“I never saw him again. It took a few months before I realized that they really did gas people.”

The Germans logged April 30, 1943, as Eddy Hamel’s date of death, but it’s not a reliable record, historians say, because the SS often waited until the last day of each month to close accounts and record who had expired. When Hamel died, probably by gas, he almost certainly did not know that his wife and sons (along with Greenman’s family) had been exterminated within hours of their train’s arrival, months earlier. According to the surviving logs, on the day Hamel reached Auschwitz two other trains, carrying 5,284 more Jews, arrived from what is now Belarus. Of that number, 4,510—including 1,207 children—were sent directly to the buildings whose signage declared, in German, BATHROOM and DISINFECTION ROOM. Inside were fake showerheads. Sometimes the SS even handed out soap and towels.

The sheer volume of the killing at Auschwitz still terrifies, 74 years after Soviet troops liberated the camp on Jan. 27—now recognized as Holocaust Remembrance Day—of 1945. Asked what modern society misunderstands about the Holocaust, Grunwald-Spier quips, “How long have you got?” A 2018 survey showed that 31% of Americans (including 41% of millennials) believe that no more than two million Jews were killed in the Holocaust. The real number, going off decades of rigorous research, is around six million.

This is why the recollections of survivors like Greenman, who died in 2008 at age 97, are so valuable. This is why Jim McGough interviewed Greenman in his London home, in ’03, and why he has since scraped the continent’s aging archives for any mention of Hamel: “So that we don’t forget.”

This need to remember the unspeakable is why last fall James Caporusso, the head of Ajax’s American office, whose grandfather and uncle died in camps, carried a vase of flowers and a modern, Lycra-blend Ajax jersey to 503 E. 83rd St. in Manhattan. He placed them on the stoop outside Eddy Hamel’s birthplace and stood looking at the building’s original 100-year-old brick for a long while.

This is why the name HAMEL is etched on the commemorative wall in the Hollandsche Schouwburg Theater in Amsterdam. Not just to remember Eddy, Johanna, Paul and Robert—but also Eddy’s parents and his sister Estella, executed at the Sobibor camp in 1943; and his sister Hendrika, killed at Auschwitz four months before Eddy arrived; and his youngest sister, Celina, whose fate remains unknown.

“If God could get me out of the camps,” Greenman wrote in his book, “I promised that I would tell the outside world what I had seen inside.”

When Greenman, 50 years later, wrote to Ajax about his bunkmate, the club sent him its most recent media guide and a sheaf of black-and-white photos of their first Jewish player, the fleet-footed right-outside. The Ringleader.

Greenman wrote back: “I instantly looked at Eddy Hamel’s picture, the face I can’t forget, the man of calm friendliness and body warmth.

“Eddy had a good circulation and was truly warm.”