The Shutdown Corner Stare-Down

Sheldon Richardson arrived in Minnesota for his first and only season as a Viking last March, and as there is for any free agent signee, there was plenty to get used to. But more than anything, Richardson struggled to get used to one particular teammate, and one particular habit.

During practices, Xavier Rhodes, the Vikings’ All-Pro cornerback, kept standing right in front of him between plays. Rhodes would get as close as possible to the offensive huddle, practically straddling the football and he stared directly at the receiver he’d be guarding on the upcoming play. But in doing so, he blocked Richardson’s view. Bro, what are you doing here? Richardson shouted at the first practice. Move!

Fellow defensive tackle Linval Joseph laughed. “Relax, that’s just his thing,” he told Richardson.

Few teams in the league ask their best cornerback to travel with the opponent’s best receiver. Only two—Rhodes and New England’s Stephon Gilmore—followed an opponent’s top receiver in 10 or more games last season, per Pro Football Focus. Though the mentality of the shutdown corner still lives in the form of that practice that annoyed Richardson a year ago.

It’s a psychological ploy that’s nearly impossible to see on the game broadcast, but it has been passed down from shutdown corners of the past. The 6’ 1”, 215-pound Rhodes looks particularly menacing when he stands over the ball and glares into the opponent’s huddle. “It helps me get mentally focused and mentally ready,” Rhodes says. “Once I am in the front of that line, I am letting the receiver know, I’m on you. I want you to see me first before you see anybody else. I’m also telling myself, wherever this guy goes, I’m on this guy.”

Raiders great Lester Hayes has a phrase for that mindset, “Locked and loaded on a fire mission.”

Former Jets star corner Darrelle Revis picked up the stare-down after hearing stories of Hayes. When told about Rhodes’s technique, Cardinals shutdown corner Patrick Peterson laughs and says, “He got that from me!”

It was a guess by Peterson—he and Rhodes train together but have never discussed the stare-down technique. But Peterson is right.

Rhodes remembers his a-ha moment. It was the middle of the 2015 season, his third year in the league. Rhodes loves watching Peterson, the eight-time Pro Bowler; he will always watch the Cardinals game first if Arizona is included in the film study of his upcoming opponent. “I saw him in the front of the D-line and he was moving and shaking around and I was like, Oh, that is tight! Woo, I gotta steal that!” Rhodes says. “It really got to me. I understood the message, I understood what he was trying to say, to let the receiver know it's going to be a long day for you. I decided I'm gonna take that because once [my receiver] is in the huddle, I want him to see me. Nobody else, I want him to see me.”

Rhodes hasn’t looked back since. The following season, he made his first Pro Bowl, and then was named to another Pro Bowl and a first-team All Pro in 2017.

“When a team realizes you are a man-to-man corner and you are a guy that travels, they are going to try to do certain things to get you out of the game,” Peterson says. “They’ll try to get you tired, lull you to sleep, so by you doing that [stare-down], it shows the guy upstairs who is watching you that I am locked in every single play. No matter what you try to throw at me, I'm ready for it.”

Per PFF, Peterson shadowed his opponent’s top receiver in seven games this season, a decrease from previous seasons because of a defensive scheme change under a new coaching staff. Like Rhodes, Peterson also can’t take full credit for this between-plays strategic warfare. His inspiration was Hall of Fame cornerback Deion Sanders.

Sanders, now an NFL Network analyst, says he stood over the ball and waited for his receiver because he wanted to set the tone early in the game. Sanders won his first ring in the 1994 season, when his 49ers defeated the Charters in Super Bowl XXIX. On the first play of that game, he lined up over the ball and waited for his receiver. “I’m not going to tell you the receiver because I am not going to embarrass him, [we checked, it was Shawn Jefferson], but they break the huddle and he knows that he got me,” Sanders says. “I said to him, ‘It’s your birthday, and I’m your gift.’ And right then he goes, ‘Dang, I’m not the main guy, the other guy [Tony Martin] is.’ I said, ‘You got me, baby.’ So he knew right there what it was going to be, from the first play of the game.”

What do the men on the other end of the stare-down think of it? Bears receiver Allen Robinson, who Rhodes traveled with during a game last November, noticed him standing in front of the defensive line, and compared the tactic to his experience playing Revis earlier in his career.

Rhodes traveled with Green Bay’s top receiver, Davante Adams, in both games against the Packers in 2018. Adams is well aware of Rhodes’s practice, but says it has no psychological effect on him. “Most guys are in the back and waiting and then they go, but he likes to stay in the front, that's his thing,” Adams says. “I'm not looking at him because it doesn't matter who is following me, I am just going to get lined up. I'm sure [intimidation] could be what he's doing, but I'm not really paying attention to it. Hopefully that's not what he's trying to do because it doesn't affect me that way.”

So while receivers notice the cornerbacks stalking them in between plays, they downplay the impact it has.

“You can't psych a man out on a Sunday, Hayes says, “that is very difficult.”

Even if it is just a one-way psychological benefit, Revis loved this part of the game, the plays between the plays. “Standing over top of the ball, you gaze with a laser like Superman into somebody else’s eyes for intimidation,” Revis says. “I’ve looked in Tom Brady’s eyes, Randy Moss’s eyes, Terrell Owens. It's all competition, they might stare back at you.”

Revis learned the tactic from Dennis Thurman, who was his defensive backs coach with the Jets. Revis was already a Pro Bowler before Thurman arrived, but after observing him for a few weeks at practice, Thurman saw this tactic as a way Revis could improve his game, and he used Hayes as an example. “What I wanted to impress upon him was how Lester [Hayes] came out of the huddle and how he got as close to that receiver as possible,” says Thurman. “It becomes frustrating to a receiver if you are tracking him in that way and he's not having success. He can't get away from you, and what could be more frustrating than someone standing right there waiting for you to break the huddle. You’re sitting there going, I mean, will you leave alone?”

Thurman saw the frustration boil over firsthand in some great receivers, like a certain Panthers receiver the Jets faced in 2009 [Thurman won’t say who, but it’s not hard to guess—“If he read it, he’d know it was about him,” Thurman says]. The receiver caught up with Thurman walking off the field at halftime at the old Meadowlands. “He said, ‘Man, would you get Revis off me? Just get him off me, man!’ I said boy, I'll get him off you after the game, but we got another half to play.’”

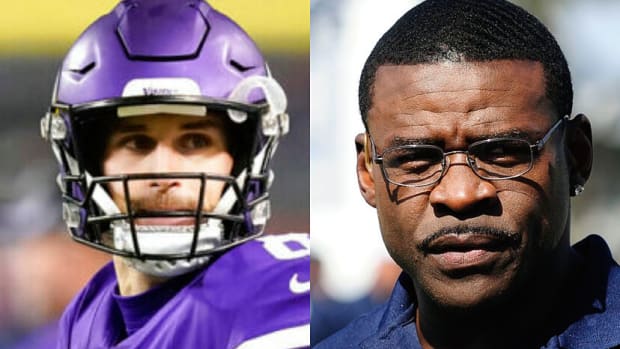

Linval Joseph says he can only remember one time when Rhodes—his teammate for five seasons—was actually in his way. In goal line situations Joseph needs to get set up quick. Facing Washington two seasons ago, Rhodes got tangled up in the defensive line on third-and-goal. The linemen had their hands on the ground ready for the snap, while Rhodes was stuck in between Joseph and defensive tackle Tom Johnson, scrambling behind the 320-pound defensive tackle to get out before the snap. Then-Washington quarterback Kirk Cousins scored on the play with a one-yard sneak. “It was goal line and they came to the ball real quick and he is stuck in the traffic,” Joseph says. “I didn’t say anything because they scored, so I just let it go.”

After Vikings games, Rhodes’s friends and family in attendance often ask him why he stands up front. They assume he just does it for the looks. “A lot of people tell me it looks cool, honestly,” he says. “You in front of the D-line and everybody behind you.”

After a few practices of Rhodes standing in front of him, Richardson begrudgingly accepted the fact that this is one territorial battle he can’t win. “Yeah,” he sighs. “Xay complained enough to the point where he gets to get in front of the ball.”

During his time with the Jets, Revis’s teammates on the defensive line frequently teased him about invading their space. “I would tell the defensive line, just move out my way,” says Revis. “They'd be like, Here come Reeves, here come the island. You want to play D-tackle?”

As a rookie on a veteran Cardinals defense, Peterson also took some heat for his tendency to stand over the ball. Arizona linebacker Paris Lenon, then 33 years old, did not appreciate the 21-year-old Peterson turning his back to him. “‘What is your young motherf------ a--- doing up here in my huddle?’ Peterson remembers Leonard shouting at him. ‘This is my huddle!’

“I was like, man, I am worried about my receiver,” Peterson says. “I don't even have to hear the call. I know exactly what I got.”

• Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.