Drawing Inspiration: Desmond King and His Brother Devon Form a Powerful Bond Through Art

Desmond King II reveled in the energy of the raucous crowd. His Chargers trailing by eight early in the fourth quarter at Heinz Field, the second-year cornerback helped get the ball back by making the tackle on a pivotal third-and-forever. Moments later, he was backpedaling to field a Steelers punt at his own 27-yard line. Sidestepping the first would-be tackler, he darted up the left numbers, zipped past two outstretched defenders and then cut diagonally toward daylight.

King’s 73-yard touchdown was a galvanizing play in a 33–30, early December win that helped establish Los Angeles as one of the NFL’s best teams. In the stands high above the end zone where King scored, his mom, Yvette Powell, nearly lost her voice screaming. And back in Southern California, King’s younger brother, Devon, watched the moment play out on Sunday Night Football in a way that only he could see: inspiration for another work of art.

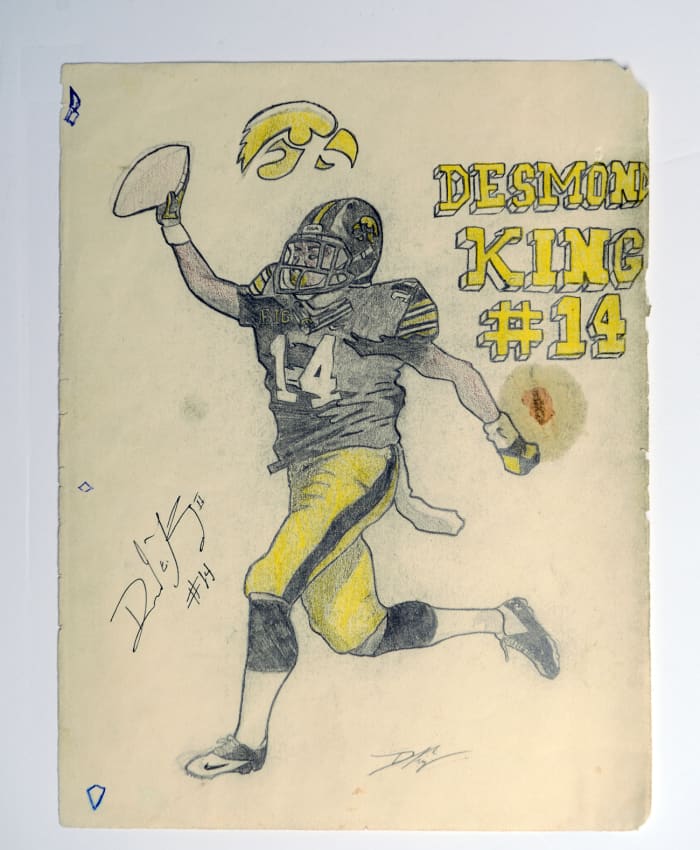

Since Desmond was a freshman at Iowa, Devon has filled sketchpads and three-ring binders with illustrations of his brother’s football career. Over time, the drawings have displayed leaps in artistic talent, with cartoonish depictions evolving into intricate lifelike portraits. Flipping through the pages on a recent Tuesday evening, Devon stopped on one of his favorites: Desmond’s first big moment with the Hawkeyes. It shows King holding the ball triumphantly above his head after recovering a Northwestern fumble and captures the finer details of his Iowa uniform: the creases in his jersey, the Nike sweatbands around his wrists, the white towel tucked into the back of his waistband.

“I thought it was cool seeing somebody draw me,” says Desmond, who hasn’t always been able to catch people’s eyes out on the field.

At East English Village Prep in Detroit, King set a state record with 29 career interceptions, but he felt his dream of playing defensive back for a Power 5 school slip away when a Michigan State coach told him he’d be better off as a running back in the MAC. King was committed to Ball State until Phil Parker, the defensive coordinator at Iowa, visited East English a week before signing day on a tip from a high school coach in the area. “Everybody doubted him, but he had great instincts,” Parker says. “That’s hard to coach.”

After an injury opened the door for playing time as true freshman, King was starting for the Hawkeyes and making impact plays like that fumble recovery against Northwestern. Just two years later he won the Jim Thorpe Award as the best defensive back in college football, with eight interceptions. But NFL teams still thought him too small (he’s 5’10”) and too slow (he ran a 4.5 40 at his Pro Day), and he fell to the Chargers in the fifth round of the 2017 draft.

Yet those instincts have made him a valuable asset on special teams and defense. He has three interceptions this season, including a pick-six of Russell Wilson, and he has thrived in the slot even against tight ends such as the Chiefs’ Travis Kelce, who had an eight-inch height advantage in Week 15 but was held to 61 receiving yards and no TDs. “Tell him he can’t do something, and he’ll go do it,” L.A. coach Anthony Lynn says. “He finds a way.”

For all his success, King doesn’t even think of himself as the most accomplished person in his family. He bestows that title on his 19-year-old brother with whom he shares a condo. “His story, and how he hasn’t let anything stop him from doing what he loves to do,” King says. “That motivates me.”

Long before Devon was a freshman at the Orange County campus of the Art Institute of California, with dreams of one day working for an animation studio, he stopped talking and doctors weren’t sure why.

At first they thought the 2-year-old had ADHD and prescribed him medicine, but Powell, a mom of four boys who worked as a medical assistant for a cardiology clinic and as a home healthcare aide, pushed for more information. When he was four, Devon was diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, a condition that affects brain development and creates challenges with communication, social skills and behavior. Devon was on the high-functioning end, but Powell remembers doctors telling her his future would likely be community college or a trade school. “I wanted him to go to college,” she says, “because I didn’t want him to think he was different from anyone else.”

During Devon’s nonverbal years, his family noticed his unusual ability to communicate through drawing. If he wanted to eat McDonald’s chicken nuggets, he’d sketch out the golden arches or the highway exit number they’d need to take to drive there. When Devon was nearly five he came home from school and showed Powell a flipbook he’d made, illustrating twins in his class getting into a tussle on the playground. “Mama, did you see this?” he asked, reducing Powell to tears upon hearing her son’s first words in more than two years. Still, it wasn’t always easy for him to have conversations. “The toughest part for him was feeling isolated,” Desmond says. “Not being able to communicate, I couldn’t imagine what that would be like.”

One of Devon’s early drawings of his brother, when Desmond was an Iowa Hawkeye.

Kohjiro Kinno for The MMQB/Sports Illustrated

Devon’s elementary school in west Detroit had limited resources, so Powell always sent him to school with art supplies, telling his teachers that drawing kept him calm and focused. “If he had a pencil and paper, he didn’t care about anything else,” Powell says. “And that’s still how it is. You have to pry his pencils away. He loves drawing, just like Desmond loves football.”

The two have always been close. The East English coaching staff created jobs for Devon, asking him to be a ball boy or hold the down markers, so he could be near his brother. Devon is a perfectionist, a trait associated with autism, so if he didn’t get a top grade in school he would retreat into his bedroom closet and shut the door. Desmond would go in and coax him out to play Super Smash Bros. on their GameCube.

In September 2012, the boys’ family received unthinkable news: Armon Golson, Desmond and Devon’s older brother, had been shot and killed in Detroit. He was 21. Desmond had taken up football because his two older brothers had, and just three days after Armon’s death, he insisted on playing in a game against Southeastern High. He ran for three touchdowns in the 39–0 win.

“Desmond made promises to his brother before he passed that he would stay on track for football and school,” Powell says. “After he lost him, it made Desmond take Devon under his wing. He wanted to keep Devon, like Armon kept him.”

After Desmond went away to Iowa City he would go home whenever he could, but the nearly eight-hour drive to Detroit was difficult to balance with a full course load and a busy football schedule. Devon would watch his brother play on TV, and when he saw him make that fumble recovery against Northwestern, he told his mom he wanted to make a drawing for him. Desmond hung it in his dorm room for his friends and teammates to enjoy. “I was inspired when people were seeing what I was doing,” Devon says.

Devon then began drawing even more—his brother’s teammates, coach Kirk Ferentz, Desmond’s fellow Thorpe Award finalists. Jackie Hargreaves liked Devon’s work so much that she commissioned him to draw two more illustrations of her son, Vernon, then a cornerback at Florida. She insisted on paying him, becoming Devon’s first customer.

Desmond could have left for the NFL after his junior season, but he fulfilled the promise he made to his mom and older brother and finished his degrees in African-American studies and broadcast journalism. But he wasn’t going back to school alone. He and his brother made a pitch to their mom: What if Devon spent his senior year in Iowa? City High was just up the road from King’s off-campus apartment, where he lived with two other students, including Charles Boyd, a close high school friend. Plus, the move would help prepare Devon for campus life. Powell was reluctant, but says, “Devon benefited more being with Desmond.”

While Powell went to Iowa for extended stays, Desmond was often the one signing permission slips and helping Devon with homework. Devon passed the ACT, making college possible. The week after Desmond was drafted, he escorted Devon to his senior prom. Devon rolled up like no student ever had: in a white sequined suit, with his big brother and three buddies from Detroit dressed like the agents from Men In Black.

Devon, with mom Yvette, Desmond (back row right) and the rest of the prom crew.

Courtesy Yvette Powell

“Devon was so proud of Desmond, but I think Desmond was more proud of Devon,” says Parker, the DC at Iowa. “You could see it in his face, that he thought what Devon was doing was more important than any of his accomplishments.”

When the Chargers picked King, he wanted to make sure it was also an opportunity for his brother. Devon lived at home in Detroit during Desmond’s rookie year, but he moved to Southern California in February, bringing his pencils and sketchpads. King is covering his tuition at the Art Institute. “Putting him in school,” he says, “was something very important to me. He saw what my mom went through with my older brother and it wasn’t positive. I took it upon myself to show him the right way, to keep his mind focused and stay on the right things.”

While King spends long hours at the Chargers’ facility, Devon takes Ubers to and from campus, where he completed four courses this semester. For the final project in his Acting & Movement for Animators class, Devon had to produce a short film. Desmond starred in it, re-creating a scene from the movie Friday. (It got an A.) The school’s Orange County campus is closing this month, so Devon plans to continue his media arts degree at UC-Irvine in the spring. He’s considering living on his own—the campus is just a short drive from his brother’s condo, and Desmond is helping him get his license—but they’ll still end up doing everything together.

The Chargers’ defensive backs call themselves the Jack Boyz, a nod to jacking, or stealing, the football. Devon—“one of the Jack Boy brothers,” says cornerback Michael Davis—joins them for bowling nights out, and he drew all of their faces in one of his most recent illustrations. You can easily spot Pro Bowl cornerback Casey Hayward grinning near the top, next to bearded safety Jahleel Addae. Rookie Derwin James, the team’s first-round pick, is unmistakable in the bottom row, second from right. After one of the Chargers’ 11 wins this season, Devon showed it to his brother’s teammates outside the StubHub Center. “It was fire,” James says. “He drew my hair right and everything.”

A few weeks ago, King wore Devon’s artwork on the field, during the NFL’s “My Cause, My Cleats” initiative. Devon says the design took him only about 10 minutes—cell-shaped letters spelling out Sickle-Cell Awareness in honor of Boyd, their Iowa roommate, who suffers from the blood disorder. King wore another one of Devon’s designs last year, for autism awareness.

“His is a similar story to mine, but his is much tougher,” King says. “I was going out there to represent him, too.”

Question? Comment? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com.