Gary Plummer Gets His Mind Right

In early May, Gary Plummer, the former Chargers and 49ers linebacker, drove to see a neurologist in Carlsbad, Calif., to learn just how badly football had screwed up his brain.

Sitting in the office, the 58-year-old steeled himself. A year earlier he had taken the first part of the NFL’s Baseline Assessment Program (BAP) neuropsychological exam. For six hours he answered questions and clicked through problems and puzzles on a computer: letter-number sequencing, matrix reasoning, geography. Some questions reminded him of the SAT. If a train leaves Boston at 10 a.m. . . . Intermittently the doctor would ask him to repeat back a series of nouns—say, hammer, red, Wednesday and policeman. Once, Plummer would have breezed through such an exam. As he was quick to tell people, he got into Cal on academic merit, not because of football. He read dozens of books a year, rotating among classics, nonfiction and mysteries. He had long taken pride in subverting the stereotype of the dumb jock.

But 15 seasons of pro football had taken a toll. In the decade after his retirement, in 1998, Plummer began to notice changes. The headaches that plagued him as a player didn’t abate but instead worsened, lasting hours and sometimes days. “Like a spike being driven behind my right ear,” he says. Loud noises agitated him. So did bright lights. Eventually, he became anxious and depressed. He rarely slept more than an hour or two at a time. He couldn’t concentrate long enough to read, so he began listening to audiobooks. He relied on his wife, Corey, to remember details and manage his schedule.

When, in 2014, he finally saw a clinical psychologist for an assessment of his mental health, Plummer struggled to answer basic questions. “I felt like a f------ moron,” he says. ”The longer the test went on, the stupider I felt.” Afterward the psychologist told Plummer he suffered from major neurocognitive disorder due to repetitive traumatic brain injury. “The early stages of dementia,” says Plummer.

Theoretically, his condition should have worsened in the years since, making his story depressingly similar to so many other former players’. And yet, entering the neurologist’s office this May, Plummer felt cautiously optimistic. Confident, even. He believed his efforts were about to pay off.

Increasingly, research links head trauma to Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, in addition to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a degenerative brain disease in which a protein called tau slowly kills off brain cells. Still, much of the science about head trauma remains frustratingly murky; CTE, for instance, can’t be diagnosed in the living. Even the definitions of “concussion” and “cognitive impairment” change every couple of years. One fact seems exceedingly clear, though: The more hits you take to the head, the more dangerous it is.

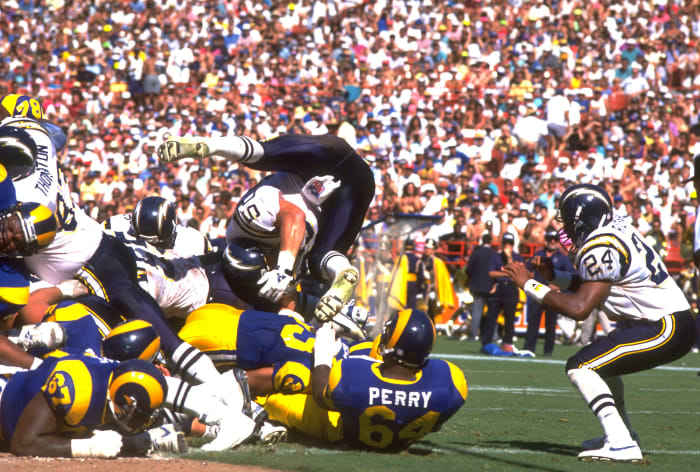

Plummer estimates he suffered between 2,000 and 4,000 concussions, if you include the least severe, or Grade One. He knows some will scoff at this number but suggests they do the math, factoring in not only the hundreds of games he played but all the full-contact practices, scrimmages and preseason tussles. From an early age, Plummer—undersized, unexceptional by most physical measures—repeatedly beat the odds. An all-state guard at Mission San Jose High in Fremont, Calif., he received no Division I offers. George Seifert, then a Stanford assistant, was interested until he saw Plummer in person and deemed him “too small to play Pac-10 football.” So Plummer went to community college in Ohlone, Calif., and, two years later, walked on at Berkeley as a 6'2", 220-pound nosetackle. Undrafted by the NFL, he played three seasons with the Oakland Invaders of the USFL. When the league folded, he got a tryout with the Chargers in 1986. By midseason he was their starting linebacker. BEST PLAYER NOBODY EVER REALLY WANTED, read the headline of an L.A. Times profile.

Undrafted by the NFL out of Cal, Plummer played three years in the USFL, then 12 more with the the Chargers and Niners.

Peter Read Miller for Sports Illustrated

Plummer had grown up lower-middle class. He recalls watching his father, a policeman, descend into agoraphobia. He was determined to live a different life, to turn fear to his advantage. So he used it as fuel in the NFL, believing every game would be his last. He spent nights in his $70,000 home gym, the one with squat racks and hip sleds, running 18 mph on a custom-built treadmill until he threw up. A nutrition science major at Cal, he tracked every bite of food in a computer program, calibrating vitamins and complex carbs. On the field, he played on the brink of madness, trying to win every drill and intimidate every opponent, always willing to “grab a handful of nutsack” at the bottom of the pile if it meant gaining an edge. When a trainer called him over after a collision, raising a hand to ask how many fingers Plummer saw, he would ignore the dizziness or nausea or tingling in his arm. “This many,” he’d bark back, raising a middle digit. There was no time to worry about the consequences. Besides, wasn’t that what the helmet was for—to protect you?

When the first reports detailing the dangers of concussions appeared in the 1990s, Plummer scoffed at them, just as league officials did. (“Concussions are part of the profession, an occupational risk,” Elliot Pellman, Jets team doctor and later league-appointed chair of the NFL’s Mild Traumatic Brain Injury committee, told Sports Illustrated in 1994.) Same for the seminar that Plummer’s agent, Leigh Steinberg, persuaded him to attend. “It was very progressive of Leigh, but of course I didn’t know it at the time,” says Plummer. “As linebackers we were like, ‘This isn’t for us. This is for those p------ on the other side of the ball.’ ”

In retrospect, Plummer is embarrassed by how he acted: “I begrudgingly sat in the meeting, and it was a panel of about eight people that were experts from around the country. They were neuroscientists, academics and surgeons. I’ll never forget when the guy gave the definition of concussions. I’d never heard of a Grade One or Grade Two concussion. A concussion is when you get knocked out, dude, end of story.” Then the doctors told the players that seeing stars counted as a concussion, and that if you experience the sensation you need to think about sitting out a week. “I literally jumped out of my chair and said, ‘As a middle linebacker, if I didn’t have five to 10 of those a game, I didn’t play that week,’ ” Plummer recalls. “I was flabbergasted that he was suggesting that me, a tough guy, would sit out. Are you kidding me?”

Plummer launched himself like a ‘fleshbomb’ into tackles and estimates he had 2,000 to 4,000 concussions while playing. Whatever the count, he shook them off, as was the practice in his day.

Stephen Dunn/Getty Images

Instead, Plummer told the media that “pain is acceptable to me.” He took pride in playing with two six-inch pins in his thumb, on having a knee scoped on a Tuesday and lining up on Sunday. Game days, he took Toradol, a potent anti-inflammatory that temporarily masked the pain. The rest of the week, he ingested Percodan and Indocin until they gave him ulcers, at which point he ramped up to Prednisone, a steroid that can trigger fits of aggressive behavior. During those years Plummer wasn’t always the best husband, or father to his four kids—he realizes that now—but he never slacked as a football player. And back then, that’s what seemed to matter the most.

In the end Plummer played in 243 professional games (48 under Seifert in San Francisco, the ultimate vindication) and earned a Super Bowl ring in the 1994 season. He underwent 15 surgeries during his career, and says he knew better than to take the 49ers’ offer of $200,000 rather than continuing health coverage. Left hip replacement followed, then eight more post-career operations. He had always assumed his body would break down; that was price of playing. What he didn’t expect—what none of his teammates foresaw—was the other toll. Bodies can be repaired; brains can’t.

In retrospect, Plummer’s descent was so gradual he barely noticed it at first. Always a great quote, he got a job as a 49ers radio analyst in 1998. Obsessive about staying in shape, he biked 10,000 miles a year, lifted and played backyard hoops with his two sons. Step by step, though, his world began to fray. In 2005 he and his first wife endured a rough divorce. He experienced bouts of anger and depression. Chronic sleep deprivation. Dark thoughts. Who would miss me if I weren’t here? Would anyone give a s---? In 2011 he married Corey Stein, who works in human resources and was a Chargers cheerleader. Having seen football’s brutality up close, she worried about her husband, and remembers waking up in the middle of the night, finding him gone from bed, at which point, sweating, she feared the worst. The next morning she would beg him to see a therapist.

But each time, Gary waved her off. There was nothing to worry about, he’d say. This stuff was just a phase. It would pass.

And then, says Corey, “Everything changed.”

Plummer was at home on the morning of May 2, 2012, riding a recumbent bike and watching TV, when the news report flashed on the screen: Chargers legend Junior Seau had been found dead in his home of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the chest.

Plummer and Seau had met at San Diego’s training camp in 1990. The two quickly became workout partners, the veteran linebacker mentoring the rookie. Each had a prodigious work ethic, and they delighted in lighting up opposing running backs, in being the baddest dudes on the field. Seau came over for dinners at Plummer’s house—“Junebug,” his family called him—and the pair volunteered at a local charity, the Bates Street Community Resource Center. Gregarious, handsome and successful, Seau was the kind of guy who had hundreds of best friends. To most, his seemed a charmed life. “Mr. San Diego,” as Plummer puts it. But after retiring in January 2010, Seau began his own descent: a domestic violence accusation, heavy drinking and gambling, a car crash that some thought to be a suicide attempt. Plummer spent less time with his friend; when he did, Seau was surrounded by unfamiliar faces. Says Plummer, “It was like he was a different person.”

Now, as Plummer sat on the bike, tears rolling down his cheeks, he thought back to the last time he had seen Seau, at a charity golf event a couple of weeks earlier. Though smiling and slapping everyone on the back as usual, Seau seemed off. Vacant. Plummer pulled him aside.

“You good, man?” he recalls asking.

“Yeah, I’m good. I’m good,” Seau said, smiling.

“No, dude, what I’m asking you is, are you good?”

Seau had wrapped a thick arm around his friend, looked him in the eye, and assured him he was. Plummer had bought it.

And now this. Plummer felt a stir of emotions: guilt, fear, despair, anger. Within minutes of the news breaking, old friends and teammates began to call. As a player, Plummer had been the guy who had your back, who gave it to you straight. “An awesome teammate,” says Ken Norton Jr., the former San Francisco linebacker. “He made everyone around him better.” Now, these men looked to Plummer for consolation, for perspective. “Bro, is this going to happen to us?” asked Steve Young, the ex-Niners quarterback. Plummer tried to explain away the tragedy. Junior had so much else going on. The suicide wasn’t about football. And, at the time, this seemed plausible; it wasn’t until nine months later that doctors would discover Seau suffered from advanced CTE, causing parts of his brain to waste away and triggering a potential range of symptoms, from aggression to emotional instability to memory loss.

The reporters called next. As always, Plummer was candid. He cried on air and, in an era when it was rare, spoke about the prevalence of depression among former players, acknowledging Seau’s struggles and his own. When Corey returned from work she found her husband still on the phone, pacing, doing one interview after another: San Francisco, San Diego, Boston. She knew the questions would never stop, and that Gary would keep answering them. She worried that he was ignoring the warning signs in his own life, that his path was too similar to Seau’s. Eventually, she walked over and yanked the phone out of his hand. No more interviews today, she said. Then, carrying two beers, she led him to their backyard to sit in silence.

The next morning she booked him a same-day therapist appointment; not to be assessed, but just to talk. “You’re going,” she told him. “I just can’t have you be next.”

This time he didn’t fight it.

It was hard at first. In 2012, public awareness about the danger of concussions remained relatively limited. It would be another year until League of Denial came out (a book in which Plummer appears, recounting the meeting with Steinberg), and three more until the movie Concussion.

Like many former players at the time, Plummer felt “almost guilty about complaining.” They were wealthy athletes. Who were they to whine? “I can’t tell you how many phone calls I got from relatives and friends asking the same thing after Junior died: ‘What the f---? That guy had the world by the balls. What did he kill himself for?’ ” Plummer says. “I knew exactly what Junior was thinking: ‘I don’t want to hurt anyone. I just don’t want this foreign brain. This isn’t me.’ ”

Music, from Mozart to new age, offers stress relief for Plummer, one of his many tools for settling his mind.

John W. McDonough for The MMQB/Sports Illustrated

Plummer understood he needed to do something, but what? He continued therapy, if reluctantly. He tried yoga after hearing it eased anxiety. But squatting alongside fit women who effortlessly bent their bodies, he felt embarrassed and clumsy. Meditation proved equally frustrating. He couldn’t still his thoughts for five seconds, let alone a minute. “I don’t know who all of it was more for at that point,” he says. “Getting Corey off my back or because I knew what was good for me.”

His efforts were scattershot. He googled “brain help” and “getting over anxiety.” He downloaded the Babbel app after reading that learning a language can help create new synaptic connections, only to give up after a few weeks. He bought a guitar that plugged into his computer, hoping to learn to play, but found his fingers—broken and dislocated so many times—fumbled at the task.

The previous year, while doing radio work for the Pac-12 network, he’d blanked out on the air—for three to seven seconds, he’s told. Now, at Corey’s urging, he stopped working to focus on his health. Fortunately he had the financial resources to do so. Forever fearing his next season would be his last, Plummer had spent his NFL summers working in landscaping and construction with his brother, eventually learning enough to buy apartment buildings and condos and oversee their renovations. (As a player he earned about $7.5 million over his career.)

Meanwhile, a class-action lawsuit against the NFL, filed by former players and family members, was proceeding. The sides settled in 2013, with the league providing $765 million to retired players shown to be suffering cognitive or neural impairment. (In April 2016 the amount was revised to $1 billion.) As the news spread, Plummer spoke to dozens of former teammates. Many felt deceived by a league that promoted violence without worrying about the repercussions. Others were confused by the settlement’s bewildering red tape, which could be navigated with the help of 300 FAQs. What are we supposed to do? Who are we supposed to call?

In December 2014, at the urging of his lawyer, John Lorentz, Plummer saw a clinical psychologist for a preemptive assessment and received that first, chilling diagnosis: major neurocognitive disorder. Plummer was scared but also relieved; he wasn’t imagining things.

He began having the inevitable discussions with Corey. What happens when this progresses? Was she prepared to care for him? She had already gone part-time at her job in order to be around more. Plummer had increasing anxiety around social situations, plans and travel. Corey took to doing his packing and managing his schedule, only telling him about an event in the days just before and only making commitments that could be broken.

At the same time Plummer built up his regimen. He stuck with the yoga, encouraged when his headache disappeared for a few minutes during savasana, the final resting pose. He listened to The Art of Happiness by the Dalai Lama and tried to embrace the concepts it espouses, including that happiness is determined by one’s state of mind, not external factors. He tailored his diet and workout schedule for brain health. After Young told him about music therapy, and how it provided stress relief, Plummer read up on it, learning how soldiers with PTSD had found succor through classical music. He listened to Mozart, Bach and the Swiss harpist Andreas Vollenweider, eventually installing Sonos speakers throughout his property. At the urging of his therapist, he says he tried to “stop competing at everything and work on just being”—but damn, was that hard. “It’s not like a light switch,” Plummer says. “I’d been a tough guy for 38 years. When you’re done playing, you don’t suddenly go back to who you were when you were seven.”

Most of all, though, Plummer gardened. After the divorce, he had taken it up out of spite, to prove he could do a better job than his ex-wife. Now he tried to enjoy the process, tending to his sprawling backyard for four or more hours a day, weeding, planting and hand-watering the blossoms of nasturtium and bougainvillea, the clumps of brilliant pencil cacti, and towers of vegetables. He felt that it helped, marginally at least. The way Plummer figured it, if he tried 20 tactics and each one helped just a little bit, well, that might add up to something larger, right?

It’s 10 a.m. on a late April day, and Plummer is wearing a floppy sun hat and watering the flowers in the front yard of his two-story house in Scripps Ranch, an upscale community of winding roads and eucalyptus groves about a half-hour drive north of San Diego. Even though it’s 72º, Plummer’s white athletic shirt is soaked with sweat. His dog, Teddy, an 11-year-old Shiba Inu, sticks close.

Plummer heads into his house, gait strong despite all the procedures. Though missing his familiar mullet and mustache, he still looks like a football player: fit, top-heavy torso, thick neck, telltale scars visible below his shorts.

Over the course of two days, Plummer shows me the life he now leads. Here, next to his bed, is the essential oil vaporizer, redolent of lavender, which helps him sleep. (Plummer is a big proponent of essential oils.) Here, in his upstairs steam shower, the 10 pennies he moves and stacks as he does his midnight exercises—dips, squats, step-ups, side bends, 15-pound curls, shrugs, one-leg balancing—aiming for 1,000 reps in 120º heat as his waterproof stereo plays new-age music (which he has also embraced along with classical). Here’s the vape pen he began using after hearing that cannabidiol helped with depression, and, in the kitchen, the MMF Hydro powdered supplement he drinks for “improved brain cognition.” To maintain a weight of around 250 pounds he uses a SodaStream, adding a hint of juice to each glass from one of the dozen-plus fruit trees in his yard. As he tells old football stories about “motherf------” opponents and becoming a “fleshbomb” when he launched into ball-carriers, the veins on his forehead rise and his body tenses and you can feel the old intensity, like heat rising off him.

Over lunch, he and Corey recount the process of trying to navigate the tests associated with the NFL settlement, and getting benefits, with the attendant forms and emails and lawyers. “To be honest, it’s all so confusing,” says Corey. “They tell us one thing, then another. I can’t keep it straight. And they give you as little information as possible. The communication could not be poorer, less inviting or welcoming for anyone to want to participate.” It makes one wonder how bewildering the process must be for former players who live alone, without the benefit of a Cal education or a spouse with a background in the game, especially those with significant cognitive impairment.

To qualify for compensation requires completing a dizzying number of steps, including two paired exams: the first from a neuropsychologist (the one Plummer took in 2017), then a second from a neurologist (the one he took last May). An NFL-approved neurologist then weights each test and arrives at a conclusion, dividing former players into one of four categories: no cognitive impairment, minimal cognitive impairment (known as Level 1), moderate cognitive impairment (Level 1.5, which qualifies for monetary damages) and severe impairment (Level 2, significant monetary damages).

Plummer has come to believe that his regimen is making a difference not only in his life, but also in the health of his brain. Whereas he felt lost during his 2014 assessment, he came away optimistic after taking the first part of the BAP, in ’17. It was like his mind was clicking again. Continued progress in the ensuing year had only encouraged him. Headaches became less frequent, less intense. Last April, he had even read a book, The Call of the Wild, for the first time in who knows how long. Friends who are doctors were telling him that he seemed fine, as far as they could tell. And, if this was true, it suggested something unusual, if not unprecedented: that Plummer had not only found a way to manage and mitigate his symptoms, but that he had also gotten better.

In person, he makes a convincing case, speaking with a true believer’s zeal as he espouses neuroplasticity—the ability of the brain to reorganize itself and form new neural connections—and a life unmoored from football. He talks about going to Vienna and listening to Mozart in a concert hall, the first time he had seen an orchestra. He says he “cries like a baby” when he listens to memoirs about mortality such as The Bright Hour. Sure, the old Gary still flares up—“you should see him doing the dishes sometimes, when I’m like, just chill out,” Corey says of her husband’s full-throttle approach—but it’s a process. “You have to learn how to be a completely different human being,” he says.

Plummer tries to explain this to old teammates, or to coaches who call asking him to join their staffs. There’s more to life, he tells them. “As a football player, you’re taught to never show pain, and you become hardened,” he says. “This diagnosis has given me the opportunity to discover things about myself and life that I never knew existed before. Love at a different level and appreciation at a different level. It’s almost freakish how much I enjoy flowers and the beauty of them.”

As heartened as he is, he stresses that his progress was “very slow” and “very, very hard” and that he often wanted to quit. That what works for him might not work for others. That everyone has to find his own combination until he figures out what works. But what do you have to lose? At this point Plummer has watched more than a dozen teammates and friends die, each time wondering how much football might have hastened their demise. With each passing month comes another sobering reminder. The day before my visit, he had returned from an end-of-life celebration in Montana for old friend and 49ers teammate Dwight Clark, who would pass away from ALS within two months. “With that perspective, we couldn’t give a s--- if we get any money from the lawsuit,” says Corey. “You just want to stay healthy.”

Plummer’s wish is that his story can provide a glimmer of hope, or maybe a roadmap for others. “I just want people to know that this stuff is real,” he says as he walks his dog. “Because it’s not just happening to professional football players. Anyone who’s experienced PTSD, go get help. Toughness was a great character trait while I was getting paid for it, but no one’s paying me to be tough anymore. What a fool I’d be to think that going to my grave it says, ‘Here lies one of the toughest guys ever. Congrat-u-f-------lations. Your toughness led to your demise.’ ”

He pauses. “I guess I want people to know it isn’t all doom and gloom. That having concussions isn’t the end of life. There’s still fulfillment. There’s still the ability to find joy and happiness.”

It all sounded so reassuring. But is it even possible from a medical standpoint—to reverse dementia? Could this be a fluke, a placebo effect, wishful thinking?

Robert Stern is a clinical neuroscientist at Boston University School of Medicine and a leading expert on CTE and Alzheimer’s. He explains that dementia isn’t an illness or a disease but rather a syndrome, making it an imprecise diagnosis. If you have enough cognitive impairment to interfere with your daily life, then you have dementia—but of course this depends on what you do in your daily life. Even the phrase neurocognitive impairment, which is used as a classification in the NFL suit, is new, and it doesn’t match with the accepted text of the field, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition. In addition, Stern says, the NFL’s designations don’t make sense: Level 1 is analogous to mild cognitive impairment, but Level 1.5, which is the first level that can be compensated, “is actually a pretty significant amount of dementia” and “such a person might not be able to live independently.” Stern was so perturbed by this all-or-nothing classification system that he filed an affidavit in the case.

Definitions and diagnoses related to concussions and cognitive function are often imprecise; all Plummer is sure of is that he senses improvement.

John W. McDonough for The MMQB/Sports Illustrated

So, did Plummer ever suffer from dementia? That depends on the doctor who saw him. Did he suffer thousands of concussions? That depends on how you define a concussion, for there is no objective diagnosis. Still, Stern says, “Whether Gary had 2,000 concussions or 20, he was a linebacker for many years and got his head hit thousands and thousands of times where, even if it would not be diagnosed as a concussion, it would definitely be considered subconcussive impact where the brain is still getting the same kind of jolting.”

As for reversing the process, that’s where, as Stern puts it, “The research gets more wishy-washy.” Says Alisa Gean, a neuroradiologist at UCSF who knows Plummer and has followed his progress, “That’s the holy grail: regression. Can we regress these injuries? Or is it just maintenance? I hope for Gary’s sake he’s right, but we don’t know.” As Stern explains, it’s one thing to reduce anxiety and stress so someone can focus more, another to improve blood flow to the brain, still another to slow a disease. He ticks off the most valuable strategies for those suffering from cognitive decline: yoga, losing weight, exercising, eating a Mediterranean diet, reducing hypertension, controlling diabetes, eliminating sleep apnea. Also muddying the issue is the fact that dementia can be caused by plenty of factors unrelated to head trauma, including clinical depression and Alzheimer’s.

Regardless, both doctors are impressed by Plummer. “The message is: Any of us, with or without a brain disease, would likely function better and have improved overall cognitive functioning if we did everything that Gary’s doing,” says Stern. “I don’t think this is a placebo effect. Regardless of what may or may not be happening in his brain, he’s done so many important things for his brain health that if he was on the cusp of cognitive impairment, he may have improved it to the point where he’s functioning a whole lot better, and we could all learn from it.”

Stern pauses. “But there’s one important caveat,” he adds. “It is still entirely possible that Gary has CTE, given what the potential risk is for a professional football player at his age having played linebacker. The problem is, we don’t know exactly what symptoms are caused by CTE until there may be real significant symptoms.” Like Alzheimer’s, he explains, CTE can take as long as 20 years to manifest itself, and as of yet there’s no way to diagnose it in the living, though Stern is one of a handful of researchers working on it.

And if Plummer does have CTE? “Sadly, at this point there isn’t anything that can stop it or reverse it or dramatically slow it down,” Stern says. “If he has indeed lost brain tissue from a neurodegenerative process, there’s no way to get that brain tissue back.”

In May, Plummer takes the second test. While he sits for a psychiatrist, Corey speaks with a neurologist, who asks lifestyle queries: How is Gary about hygiene? Can he drive? Does he get lost? Next come specifics: Describe something the two of you have done in the last two days, in the last two weeks, and in the last two months? An hour later, like a morbid version of The Newlywed Game, Plummer is asked to recall details of the same events.

Nearly three anxious months pass. Finally, on the morning of July 26, Plummer receives the results via email. “It’s official,” he texts. “I do not suffer from dementia, Alzheimer’s or any other neurocognitive disease.”

He is relieved. Corey is elated. They do not linger on the particulars of the 23-page report, which includes a diagnosis of clinical depression and notes that Plummer performed “within the moderately-to-severely impaired range” on learning and memory. All that matters to Plummer is the verdict: He does not even qualify for Level 1. Which means he has his brain back. At least for now.

He and Corey don’t know what comes next but say they are ready. Theirs is a guarded optimism. “Like everything in life, as long as things are working for you and you’re happy and you’re healthy, you’ll continue,” says Corey. “And we know that’s probably going to change. When that happens, we’ll talk about it and we’ll adapt however we need to.” She pauses. “It’s pending for all of us that something’s going to change. That’s life.”

Corey got Gary into therapy after Seau’s death and has been by his side since 2011.

John W. McDonough for The MMQB/Sports Illustrated

For now, Plummer is sticking with the plan. He recently spoke to a judicial conference about traumatic brain injury. He’s on the advisory board of a pharmaceutical startup with NIH funding that’s trying to create drugs to treat synapse loss. At home, he still gets headaches, but only for around 15 minutes at a time. He aims to get 15,000 steps a day in his garden, naps every afternoon and does his 120º steam workout at midnight. The din of the neighbor’s leaf blowers no longer sends him running inside.

He and Corey realize how lucky they are. To have the financial freedom to tailor their lives around Plummer’s health. To make plans but always maintain the ability to opt out. To not need the money from the settlement. To be able to live in the moment, or at least try to. And maybe this is the heartbreaking reality we’ve reached when it comes to former NFL players: that the mere idea of not having dementia in your 50s is something to celebrate.

Plummer prefers to see the glass half full. What other choice does he have? Sometimes he heads out into the garden at night, to walk and think. From his house, on a bluff, you can see out to the Pacific Ocean. The city lights are distant, and the night envelops him. He’ll lie down on the grass and stare up at the stars and, for a moment, feel at peace. Gone is the thumping of his headaches, and the churning of his mind, and the worrying over his future.

If he’s lucky, he might even fall asleep.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.