In a sport filled with strong men, Iran's Salimi now stands alone

LONDON -- In addition to exceptional strength, newly minted Olympic champion Behdad Salimikordasiabi apparently is blessed with clairvoyance. As he walked through the mixed zone in the ExCeL Arena, roughly 2,740 miles from Tehran, Salimi (this is how the weightlifting world knows him, to the relief of everyone) said people in Iran were partying in the streets because of his weightlifting gold medal.

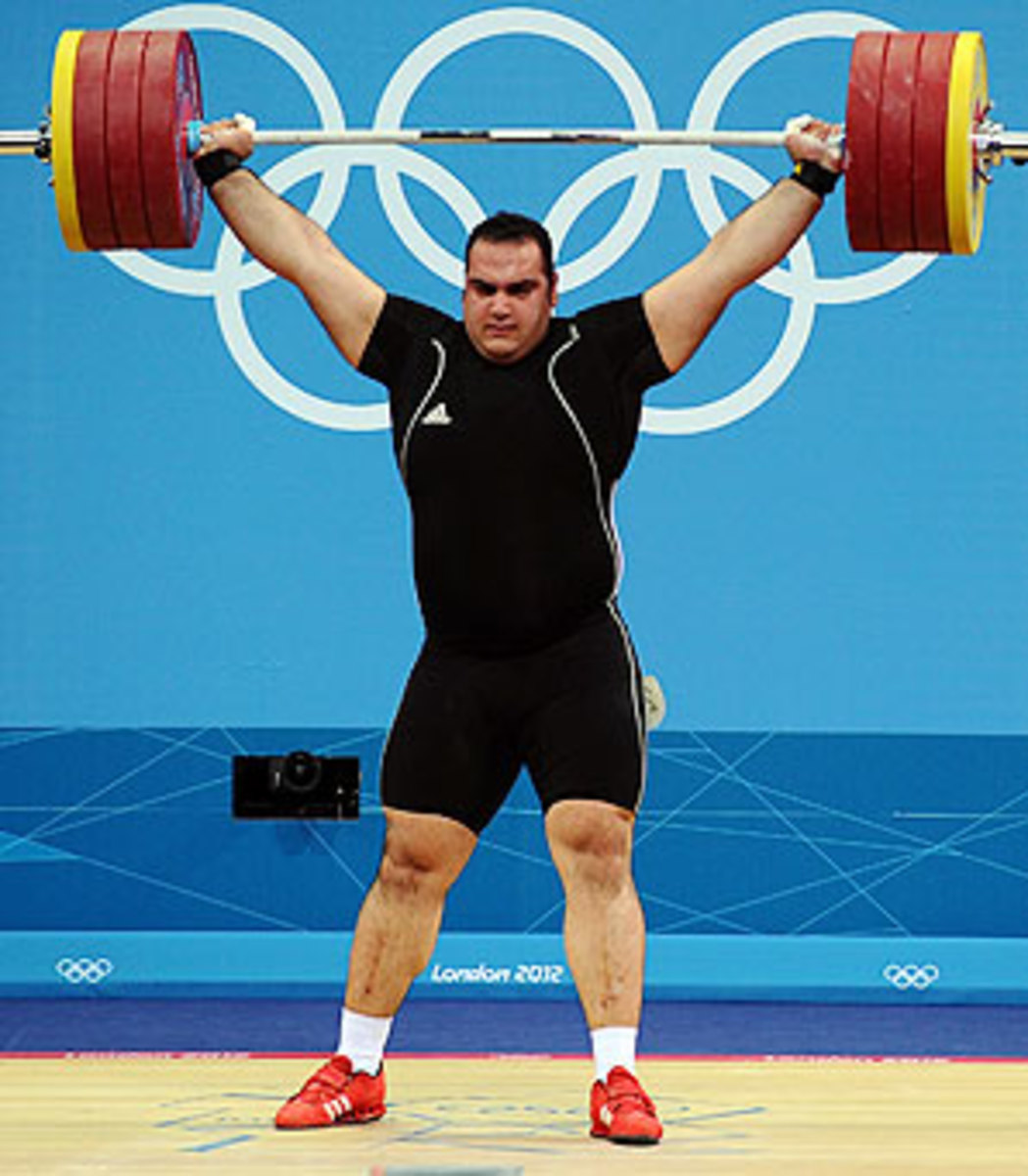

He is not a gentleman you ask a follow-up question like "Hey, how do you know?" because Salimi just had lifted 455 kilograms, which is 1,003.1 pounds -- roughly the weight of a moose. Of course, he did have a couple of goes at that weight, as they say in England, first in the snatch lift, then the clean-and-jerk, and he won the gold by a combined six kilos. Despite Salimi's gentle mien -- he has a high forehead, long thin sideburns and an ingratiating smile -- you might opt to take your chances with the moose.

Salimi was a heavy favorite to win the 105-kilogram-plus weightlifting gold medal, which would have been the case even if he had not weighed in Tuesday for the Olympic final at 370.8 pounds. The odds were 2-to-7 he would become the third Iranian superheavyweight gold medalist in the past four quadrennials because he was the two-time world champion and had won his past seven weightlifting competitions, junior and senior, dating back to 2010. Even without appearing on one of ESPN's lesser networks and demonstrating the proper technique for pulling a bus 50 yards with a rope in his teeth, the 22-year-old already had made his case as the strongest man in the world.

He demurred when asked about the unofficial title. Through an interpreter, Salimi, who speaks Persian (except when he coughs into the microphone, in which case he says "Sorry" in English), mentioned that he had trained in a specific sport and "to be the strongest man in the world is not just to lift weights." Maybe he really is not the strongest man, but it is a reasonable place to start the argument.

"He's bigger, faster and stronger than everyone else," says Jim Schmitz, coach of the U.S. Olympic weightlifting team in the boycotted 1980 Games and also in '88 and '92. "He's just a talent. If he had grown up in the U.S., he would be playing in the NFL."

The 6-foot-2 Salimi instead grew up, and up, in Ghaemshahr, Iran, a part of the country where Olympic weightlifting is basically the Super Bowl. He is coached by Hossein Rezazadeh, a two-time Olympic champion known as the Iranian Hercules. When asked if the Olympic victory had made Salimi the greatest weightlifter in a country that produces them the way USC produces quarterbacks, his countryman, silver medalist Sajjad Anoushiravani Hamlabad, said that "his standing is high. If he's not the greatest, he's one of the best weightlifters we have."

Salimi seems to understand his exalted place in the weightlifting firmament. While the others grunted and groaned and strained to steel themselves for the bar (and perhaps to make sure the crowd in the weightlifting hall fully grasped the weight of their burdens), Salimi did it almost with a shrug. When he snatched 208 kilos on his final lift, six kilos below his own world record, he raised his arms as if to say, "That's all ya got?" The Iranians in the hall -- about 60 percent of the attendees, judging by the flags -- went wild with acclaim. Salimi actually was in second place after the snatch portion because Ruslan Albegov, who represents Russia, also lifted 208 although he weighs less. Albegov, the eventual bronze medalist, is a stripling of 324.4 pounds.

But Albegov is not as explosive as the grand Salimi. The Russian started the clean-and-jerk at 240 kilos, seven fewer than Salimi. Albegov might have put a modicum of pressure on Salimi if he had been able to lock the 247-kilo lift, but he just couldn't hold the bar after he raised it over his head. Salimi already had clean-and-jerked 247 kilos with insouciance and surely could have done more, although not as much as the 264 kilos that he tried in an effort to seize Rezazadeh's world record total after first place had been secured. The delay between lifts was simply too long, and he was a little cold. Now he has an Olympic gold to keep him warm after a night of first-rate theater in a city that loves its dramas.

There is something remarkably theatrical about superheavyweight weightlifting, perhaps because the behemoths are actually on a raised stage and performing in front of an audience. Their lifts are soliloquies, one minute when the spotlight is on them alone. There are some scenery chewers, the grunters and groaners and posers and flexers and finger-pointers and barbell kissers. Salimi tends to be more modest in his gestures, maybe because he is so dominant.

Yet even as the super heavies strut and fret their minute on the stage, there is an element of delicacy to the exercise. Consider the case of 2008 Olympic champion Matthias Steiner, who was not about to win another gold medal but who now has guaranteed himself a spot in the YouTube Hall of Fame. On his second snatch lift, at 196 kilos (432.1 pounds, American), the bowed bar smacked him across the back of the neck. Three Games workers with appropriately solemn faces rushed to the stage to unfurl a blue London 2012 banner in front of the stricken Steiner, who had gone down like a bad burrito and now was being attended to by medical personnel. The modesty proved unnecessary when, a minute or so later, Steiner leaped to his feet and punched the air, a fistic thumb's up. He had to bow out of the competition before the clean-and-jerk -- the arena announcer assured the crowd that the German competitor was "OK," and then quickly added that he was being taken for X-rays to prove that he actually was OK -- but at least it appeared the National Health Service would not be unduly burdened.

There was enough heavy lifting in London for one night.