Wilt's 100-Point Game Stands as Towering Achievement in Sports

A half-century ago, Wilt Chamberlain scored 100 points in a single game, one of the landmark achievements in sports and a record that seems all but unbreakable.

The next highest NBA single-game mark is Kobe Bryant's 81 points in 2006. Bryant's total included seven three-point field goals, a shot that did not exist in the NBA until 1979.

Chamberlain's 100-point outburst in the Philadelphia Warriors' 169-147 victory over the New York Knicks was part of his remarkable 1961-62 season. He averaged 50.4 points per game along with 25.7 rebounds, the lone 4,000-point, 2,000-rebound season in NBA history. Only twice was the Big Dipper held under 30 points, both times by the Boston Celtics' Bill Russell, his main nemesis throughout the bulk of his 14-year NBA career.

"[Wilt] came with a body and an ego perfectly sculpted for dominating his game," wrote Gary M. Pomerantz in his book, Wilt, 1962. "The ego was essential. ... In 100 points there was a hubris but also a symbolic magic. In our culture the number 100 connotes a century, a ripe old age, a perfect score on a test. ... One hundred was a monument."

Early in the 1961-62 season, Chamberlain set the single-game scoring record with 78 points in a triple-overtime loss to the Los Angeles Lakers. Yet the Big Dipper's accomplishments didn't attract nearly the same national acclaim as that of other record breakers.

Two days after Wilt's 100-point game, Jimmy Powers of the New York Daily News lamented about "praying mantis-types goaltending or merely dunking the ball for astronomical totals." He added, "Basketball is not prospering because most normal-sized American youngsters or adults cannot identify themselves with the freakish stars. A boy can imagine he is a Babe Ruth, a Jack Dempsey or Bob Cousy. ... You just can't sell a 7-foot basketball-stuffing monster ..."

Chamberlain, of course, was much more than tall. The Philadelphia native was one of the most imposing blends of strength, speed and agility that the United States has ever produced. As a collegian at Kansas, the 7-foot-1 marvel ran 440-yard dash in under 50 seconds, high-jumped 6 feet, 7 inches when the world record was a fraction over 7 feet, long-jumped 23 feet and surpassed 53 feet in the shot put. He could dead-lift more than 600 pounds and was said to have defeated future Olympic shot put champion Bill Nieder in arm wrestling.

In his first varsity game for Kansas in December 1956, Chamberlain scored 52 points and grabbed 31 rebounds in an 87-69 win over Northwestern. "It's just ridiculous," said the Wildcats' Joe Ruklick, who would later be Wilt's teammate on the 100-point night. "He made me feel like a 6-year-old kid."

When Chamberlain joined the Philadelphia Warriors in 1959, he impacted the NBA like no rookie has in any sport, leading the league with record totals of 37.9 points and 27 rebounds per game. He paced the Warriors to the Eastern Division finals, where they lost in six games to the defending champion Celtics.

On Nov. 24, 1960, against Russell and the Celtics, Chamberlain set the still-standing NBA record of 55 rebounds in a game -- a mark he considered more important than the scoring milestone.

Frank McGuire, whose North Carolina team had defeated Chamberlain and Kansas in the 1957 NCAA final, took over as Warriors coach for the 1961-62 season with a simple offensive formula: Get the ball to Wilt. As Chamberlain started scoring at a record pace, McGuire predicted, "One of these nights, he's going to score 100." Russell forecast the same result, telling Newsweek, "He has the size, strength and stamina to score 100." In the three games leading up to the record-breaking night, Chamberlain scored 67, 65 and 61 points.

Fifty years later, the events surrounding March 2, 1962, recall a very different time.

• A regular-season NBA game was played in Hershey, Pa., a city of fewer than 15,000 residents best known for chocolates and as the one-time summer training site of the Philadelphia Eagles.

• Chamberlain did not arrive at the arena on the Warriors' bus but in his Cadillac that he had driven 170 miles from New York City. On his return to New York, he was accompanied by one of the Knicks' top players.

• Two future Hall of Fame football players helped warm up the crowd for the main event.

• None of the New York City newspapers sent a writer to Hershey and even the Philadelphia press corps was not fully represented. Only one photographer stayed the entire game.

• There was no television and no New York radio broadcast of the game. Philadelphia radio station WCAU's Bill Campbell provided the only call of the action.

• The team committing all the fouls in the final minutes was not behind on the scoreboard but ahead -- far ahead.

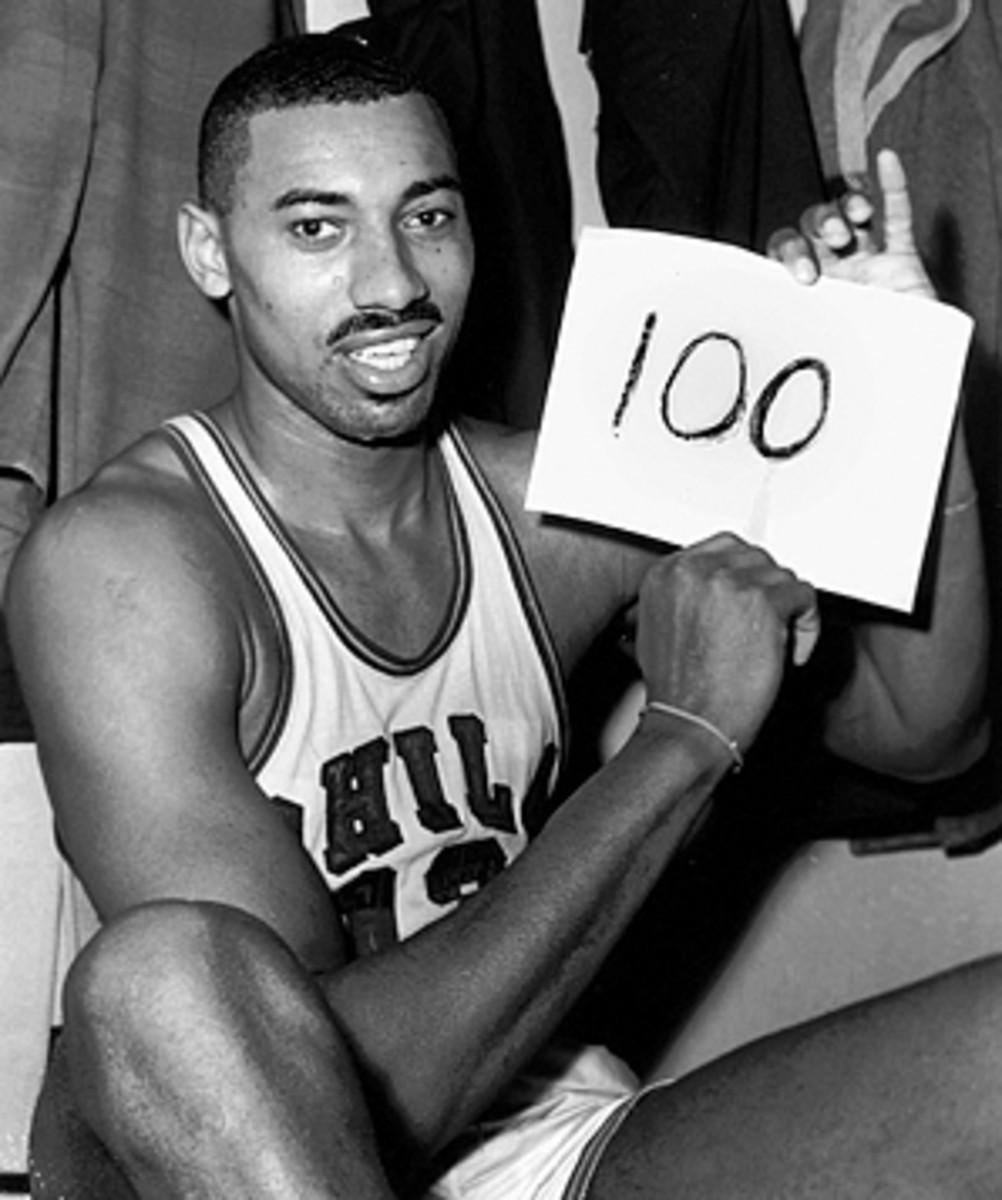

• The game's iconic photograph comes not from any action on the floor but from the locker room afterward.

• It appears that the game's final score was recorded incorrectly.

The NBA in the early 1960s was nothing like today. Basketball news ran well back in the nation's sports sections and national telecasts were rare. Home sellouts, even for the champion Celtics, were rare during the regular season, and playing at sites like Hershey was not unusual during the league's first two decades. That same season there were games in Dayton, Ohio, Rochester and Utica, N.Y., Portland, Ore., and Seattle. The Celtics played at least one game in Providence, R.I., through the 1980s.

Even with Wilt, the Warriors averaged only 4,000 in attendance in Philadelphia. Playing "off-campus" often meant bigger crowds. The night of Chamberlain's 100-point game was the Warriors' third visit to Hershey of the season but the 8,000-seat Hershey Arena was barely half-filled.

Driving his Cadillac to games was common for Chamberlain. Even though he played for the Warriors, his main home was an apartment on Central Park West in Manhattan, where he could enjoy the social life and oversee his Harlem nightclub, Big Wilt's Smalls Paradise.

Chamberlain was friendly with his teammates, often regaling them with stories of his one season with the Harlem Globetrotters. But before and after games he usually followed his own path.

To help boost attendance, the NBA often scheduled doubleheaders. Many times the first game would feature the ever-popular Globetrotters. This night in Hershey, the first game matched football players from the Eagles and Baltimore Colts, giving fans a close look at Eagles quarterback Sonny Jurgensen and Colts defensive end Gino Marchetti, both future Hall of Famers.

With only a few weeks left in the regular season, the last-place Knicks were well out of the playoff hunt, and no New York writers traveled to Hershey. Leonard Koppett of the New York Post, perhaps the city's most astute basketball writer and later the author of Twenty-Four Seconds to Shoot, was at spring training covering the Mantle-Maris New York Yankees in Florida.

Chamberlain hit his first five shots against the depleted Knicks, who were without 6-10 center Phil Jordan, their best interior defender who was ill. Darrell Imhoff, another 6-10 frontcourt player, picked up three quick fouls and would later foul out.

After the first quarter Wilt had 23 points, including a surprising 9-for-9 from the free-throw line for one of the NBA's worst foul shooters. By halftime Chamberlain had scored 41 points and the Warriors led 79-68, more like a third-quarter score in today's NBA.

Pro basketball was a faster game when Chamberlain was at his peak. Most teams averaged more than 100 shots per game, led by the Celtics' 119.6 in 1959-60. Since 1973, only the 1990-91 Denver Nuggets have averaged more than 100 shots, and Golden State led the NBA last season with 85.9.

The up-tempo game was perfect for the 7-1, 260-pound Wilt. It is unfortunate that so little film or TV tapes remain of a 25-year-old Chamberlain, before age, injuries and an extra 15-20 pounds slowed his pace.

"When the players of [the 100-point game] had grown old and gray, they would yet light up in conversation remembering the way the young Dipper ran the floor on the fast break," Pomerantz wrote in Wilt, 62. "They would speak about it with a hushed reverence as if they'd seen something otherworldly. ... On the fast break he was exquisite to watch -- in the mind's eye the other players on the court dissolved around him. The Dipper made the court seem shorter and he made it his."

After halftime Wilt and the Warriors picked up the pace on the tiring Knicks. As PA announcer Dave Zinkoff's calls grew louder, Chamberlain scored 28 points in the third quarter to reach 69, the total that matches Michael Jordan's career high in 1990.

Chamberlain's three-month-old record of 78 points was within easy reach but the Warriors sought a loftier target. Even though the game was well in hand (125-106), Philadelphia would keep feeding Wilt and see if the big guy could reach 100.

A 20-foot jump shot gave Chamberlain 79 points. Campbell told radio listeners to expect "all kinds of records from now" and there's "a little history you are sitting in on tonight."

The Knicks were not pleased. With the game long decided, they thought Chamberlain should be on the bench and not pursuing scoring glory. New York guard Richie Guerin, a former Marine who would finish with 39 points, was particularly incensed.

When New York started to milk the 24-second clock, the Warriors began fouling every Knick in sight to ensure more offensive possessions. Four Knicks surrounded Wilt when Philadelphia had the ball.

A free throw brought Wilt to 90 and another basket gave him 92 points with 2:28 remaining. Finally, with 46 seconds left, Chamberlain threw down a dunk for his 99th and 100th points. As the crowd rushed the court, Campbell shouted, "He made it! He made it! He made it! A Dipper dunk! The most amazing scoring performance of all time! One hundred points for the Big Dipper."

The floor was cleared as the Knicks scored four more points for what appeared to be a final count of 169-150. Yet somehow the final arithmetic took away three points from New York and the score went into the books officially as 169-147.

Chamberlain had converted 36-of-63 field-goal attempts and, most shocking of all, connected on 28-of-32 free throws, no doubt benefiting from the very loose Hershey Arena rims.

"I never thought I would take 63 shots in a game," Chamberlain told teammate Al Attles, who responded, "Yeah, but you made 36 of them."

In the locker room Warriors publicist Harvey Pollack wrote out the number "100" on a white sheet of paper for Wilt to hold up for AP photographer Paul Vathis. That photo, seen above, has become the iconic remembrance of the 100-point game.

Afterward, Chamberlain hopped in his Cadillac with Knicks star Willie Naulls. Hitting speeds close to 90 mph on the New Jersey Turnpike, Naulls told Pomerantz that the two discussed investments, tax shelters and why only about one-third of the NBA was made up of black players when so many more had the ability to play pro ball.

Wilt dropped off Naulls at his New Jersey home and then headed to Harlem to celebrate at his nightclub. He didn't get to bed until 8 a.m.

Jack Kiser of the Philadelphia Daily News called Chamberlain's performance "the most devastating offensive show ever staged by a professional basketball player. He earned every point."

Chamberlain had the record but Russell and the Celtics again finished with the NBA title. Boston outlasted Philadelphia in the Eastern finals, winning Game 7 109-107, the first of four Game 7's that a Chamberlain team would lose to the Celtics.

Wilt never threatened 100 points again, going past 70 only twice more in his career. The Warriors moved to San Francisco but Chamberlain returned to Philadelphia to join the 76ers (the former Syracuse Nationals) in 1965. In 1967, he led the Sixers to a record 67 victories and wins over the Celtics and Warriors in the playoffs for the NBA championship.

Chamberlain notched a second title, with the 1971-72 Lakers, who won 69 games and registered an NBA-record 33 straight wins. The man who had averaged 40 shots a game during the 1961-62 season was taking only nine nearly a decade later. But he led the NBA in rebounding and his all-around play earned him the NBA Finals MVP.

Wilt retired in 1973, content to play in beach volleyball leagues and sponsor women's track and field teams. His best-remembered post-career remark was his claim to have slept with 20,000 women, a number that longtime friends suggested would be far more accurate if one of the zeros were removed.

But on the numbers that are quantifiable, Chamberlain needs no embellishment. He led the NBA in scoring seven times, games played eight, field-goal percentage nine and rebounding 11. His career averages of rebounds (22.9) and minutes (45.8) are NBA records. His 30.07-point scoring average is second only to Michael Jordan's 30.12.

Chamberlain died from heart-related problems at the age of 63 in 1999, described by The Washington Post as "a Herculean figure of the basketball court ... a sports icon and a cultural legend."

Wilton Norman Chamberlain was never as popular as Magic Johnson or Larry Bird or as respected as Russell or Jordan. He noted, "Nobody roots for Goliath."

Yet 50 years after that night in Hershey, Chamberlain's 100 point-game stands as majestically as a Himalayan peak, a towering testament to human performance, an achievement that dwarfs all comers.