'It's My One Claim to Fame': The Untold Story of the Cubs’ Black Cat Jinx

Fifty years ago this upcoming Monday—Sept. 9, 1969—the Chicago Cubs were clinging to a small but diminishing lead over the New York Mets in the National League East. The two teams were facing each other at Shea Stadium in New York, with their respective aces on the mound—Ferguson Jenkins for the Cubs and Tom Seaver for the Mets. And then, in top of the fourth, something bizarre happened that has become part of baseball lore: A black cat appeared in front of the Cubs dugout and pranced back and forth a few times before disappearing into the bowels of the ballpark.

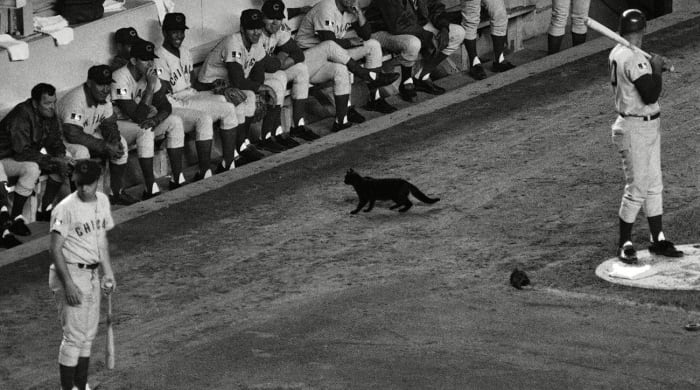

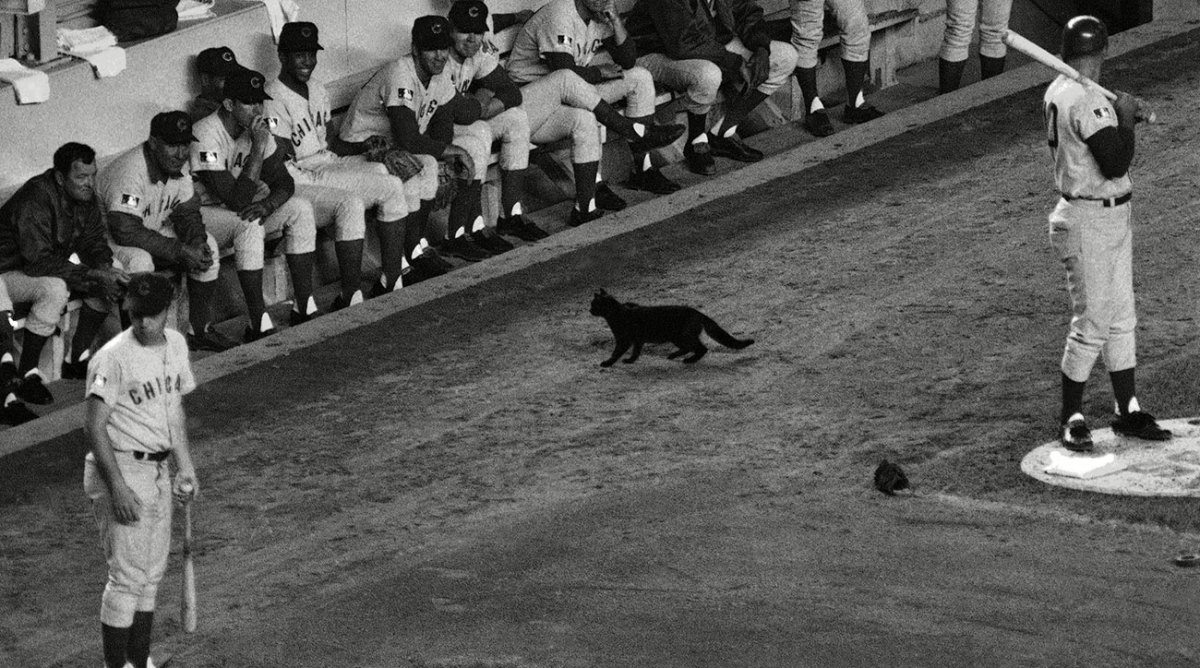

The Mets went on to win the game, the pennant and the World Series. Meanwhile, the Black Cat Incident, as it was dubbed, became another chapter in the Cubs' long-running history of misery, with the ebony feline—a notorious symbol of bad luck, of course—blamed for jinxing the team. Countless articles have been written about the incident, coupled with photographs documenting what unfolded 50 years ago this month.

Most photos of the incident show the cat approaching Chicago's dugout while being eyed by Cubs third baseman Ron Santo, who was in the on-deck circle. Therefore most accounts of the game, understandably, have featured recollections from Santo, Jenkins or other Cubs players who were in the dugout. This one, though, is different.

Take a closer look at the scene and you'll notice another person in a Cubs uniform standing off to Santo's side. That was the batboy. Like most batboys, he was anonymous, overlooked and forgotten. His name is Jim Flood, and the improbable story of how he ended up in the catbird seat for one of the most storied moments in baseball history has never been told—until now.

Flood is now 67 years old. He's a lifelong Chicagoan, a successful attorney and a rabid Cubs fan. And even 50 years after the infamous game, he remembers that night at Shea Stadium vividly.

"I can't believe it's been 50 years," he says. "It's my one claim to fame."

Flood got to be a Cubs batboy by virtue of attending DePaul Academy, a local Catholic high school. The Cubs' legendary clubhouse manager, Yosh Kawano, would call the school every two years and ask the head priest for suitable batboy candidates.

"He'd say, 'Pick me two guys who are hard-working and who you're willing to let out of school a bit early so they can be here for the day games,'" Flood recalls. "That's how I got the job in 1968."

Flood went through some initial jitters and a batboy's version of rookie hazing (before his first game, a player told him to go knock on the umpires' dressing room door—the one that said "Keep Out"—and ask for the "key to home plate," which turned out about the way you'd expect) before settling in as a well-liked member of the team's support staff. He enjoyed suiting up in his Cubs uniform, getting pointers from the players and having a front-row seat for all the ballgames.

By 1969, though, Flood was no longer a full-time batboy. "I had graduated from high school in May of ’69, and the military draft was all over me," he recalls. (He later served in the Navy Reserve.) "So I was mostly in the clubhouse that year, but I did go out on the field sometimes."

The Cubs were in first place for most of that season. But by the time they limped into New York for a September series with the Mets, their once-formidable lead had dwindled to a game and a half. Batboys don't usually travel with a team on the road (the home team typically supplies the visiting club's batboy), but Flood saw an opportunity to help his struggling team.

"They were really slumping," says Flood, "so I called Yosh and said, 'Do you mind if I come out there?' He said, 'Sure, maybe you'll give us some good luck.' He liked the idea because the players all knew me and felt comfortable with me." It was too late for Flood to catch the team charter, so he got on a stand-by flight to New York and joined the team at the ballpark, where several of the players told him, "We're glad you're here. Get in uniform!"

Consider the irony: A key witness to one of the most infamous bad-luck stories in Cubs history had gone out of his way to be there in order to provide good luck.

But a few more pieces still had to fit into place before Flood could have his photo op. He was alternating with the Mets' usual visiting batboy that night—"He'd go out for an inning and then I'd go out for an inning," he recalls. So even though he was there at the ballpark, he could have missed the black cat moment.

As it happens, he was on batboy duty in the top of the fourth. With Billy Williams at the plate and Santo on deck, the crowd suddenly got very, very loud. Flood tried to ignore it, figuring it was probably a response to a new sign being held up by Karl "The Sign Man" Ehrhardt, a Mets super-fan who was famous for displaying motivational and occasionally ridiculing placards during games.

"Then I heard Santo go, 'Oh man, we're f----- now.' And that's when I saw the cat."

Although it's impossible to confirm Santo's quote (he died in 2010), photos and video footage appear to back up Flood's account of the scene. The most famous photo of the incident shows Flood looking away, apparently unaware of the cat's presence. But a look at the extended video shows that he eventually turned and watched as the cat scampered away:

Flood's primary memory of the cat is that it was creeping toward Cubs manager Leo Durocher, who was seated in the dugout. "He was saying, 'Somebody get that f------ cat outta here. Get him away from me!' I didn't know if I should laugh or what. I mean, I was a kid. But we were playing like crap, and now this."

The Cubs scored their only run of the game that inning (Santo knocked it in with a single), but they went on to lose the game and soon saw their season fall apart. "I don't know if it was because of the cat," Flood says, "but we played terrible after that. The Mets blew right past us."

Flood didn't realize his date with history had been captured for posterity until about eight years later, when a Cubs player—he forgets which one—wrote a book that included the famous black cat photo. Other fans might have shied away from the memory of such an infamous moment, but Flood embraced his brief brush with fame. He cut the photo out of the book, had it enlarged and framed, and for many years had it hanging on the wall of his law office, where he proudly showed it to friends and colleagues. At one point he even got Santo to sign it, although he says the ink has largely faded by now.

That print is now packed away (it's bound for Florida, where Flood plans to retire next year), but the black cat photo is still special to him. He uses it as the desktop image on his computer and also has a version on his phone to show friends.

Of course, it got a lot easier for Flood to talk about all of this after the Cubs won the World Series in 2016. "That season, friends were telling me, 'Don't come to the game and stay away from any black cats and goats,'" he says. When the Cubs finally did win it all, did his mind roll back to that night at Shea Stadium 47 years ago?

"I didn't even think about it," he says. "I cried like a baby for 45 minutes."

It's worth noting that Flood has always loved cats and currently has four of them. What's more, one of them is black and named Fergie, after Ferguson Jenkins. So while the Cubs may have had a black cat jinx, Flood was never too worried about that old black magic himself.

Paul Lukas is a lifelong Mets fan and a longtime cat owner (although his cat isn't black). You can read more of his writing — mostly about uniforms, but also about peripheral topics like batboys — on his Uni Watch Blog, plus you can follow him on Twitter and Facebook, or sign up for his mailing list so you won't miss any of his SI columns. Want to learn about his Uni Watch Membership Program check out his Uni Watch merchandise, or just ask him a question? Contact him here.