As MLB Continues to Evolve, So Does David Cone

It’s the Friday night of Memorial Day weekend and David Cone is back in town for work. His business is baseball, just not in the way it once was. His pitching days are over—well, from the mound, anyway.

Cone, 56, has returned to his hometown of Kansas City as a broadcaster for the New York Yankees after a few weeks away from the booth. He’s been off promoting his new memoir, Full Count: The Education of a Pitcher. The book was released in mid-May and debuted 13th on The New York Times’ nonfiction best sellers list.

That the memoir simultaneously tells Cone’s life story and provides an in-depth study on the art of pitching is fitting; in fact, it’s by design. There’s no separating Cone’s journey to adulthood and his evolution as a pitcher, and his current broadcasting career is an extension of that.

“I think he misses pitching every single day of his life, so he’s got the next best thing, where he can analyze it from afar,” says Michael Kay, the Yankees play-by-play announcer for the YES Network, who called games Cone pitched and now broadcasts alongside him.

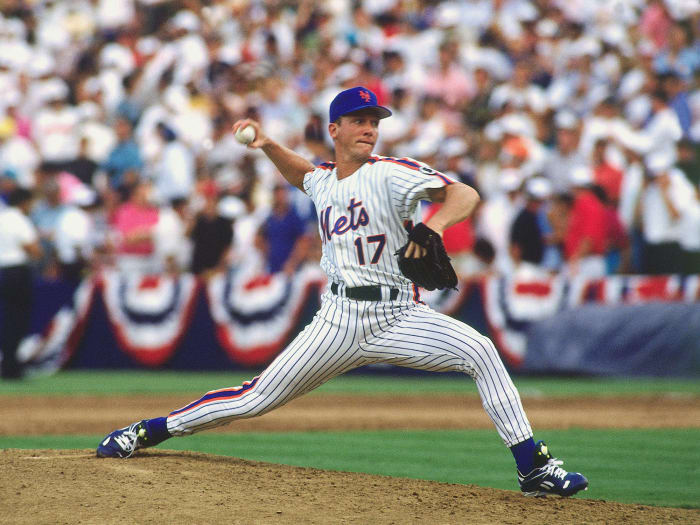

Cone’s transformation from maniacal workhorse atop the Yankees rotation to ambassador of analytics in their broadcast booth is not as drastic as one might think. Despite a willingness to throw 160 pitches in a start, he was never simply a reckless gunslinger on the mound.

With the wealth of analytics, hyper-involved front offices and advanced player-development technologies, baseball has become more cerebral each year, and in the process, Cone’s turned into one of the most articulate voices in today’s baseball landscape. Thursday marks the 20th anniversary since Cone’s crowning achievement of his 17-year career, when he recorded the 16th perfect game in MLB history. He’s remained relevant in the years since because of his willingness to adapt as the game has changed.

To understand the broadcaster Cone is now, you have to understand the pitcher he once was.

He always wanted to be a pitcher, from the time he first picked up a ball for practice with his father, Ed, at Budd Park in Kansas City. His father was his first and best coach, Cone says, a disciplinarian whose style was closer to Bobby Knight and Earl Weaver than your average Little League skipper.

It makes sense, then, that Cone became the bullish, hot-tempered righthander who took the mound every fifth day for nearly two decades. On his way to the show in the Royals farm system, he’d argue with pitching coaches if he didn’t trust what they were teaching him, and he wasn’t afraid to defy their commands when he didn’t agree with them. Blanket solutions and one-size-fits-all approaches angered him, because it works was never a satisfying explanation. He needed to understand why at all times.

For example, the Royals had an archaic rule that prohibited their pitchers from throwing 0-2 pitches in the strike zone. Cone, who was more concerned with efficiency and getting hitters out than following unnecessary limitations, rebelled against those orders when he saw fit.

He also was steadfast in his commitment to his drop-and-drive delivery style, which his minor league coaches were convinced would lead to arm injuries. If anything, Cone says, his pitching motion, dropping his body down during the windup and nearly scraping his back knee on the dirt, helped take the pressure off his right arm.

Cone modeled his delivery after Hall of Fame righthander Tom Seaver, which Cone learned from his father early on in their backyard bullpen sessions. Ed knew David wasn’t going to be gifted with a large frame that would lend itself to power-pitching, so he taught his son to maximize the power that his eventual 6’1”, 180-pound body could provide.

“I think using your legs as leverage is definitely important for pitching,” Cone says in early May. “It also helps you lengthen your stride, which helps you release the ball closer to home plate and therefore making your effective velocity greater. Using your legs more should take more pressure off your arm.”

In the minors, Cone didn’t budge on those mechanics when his coaches told him to change. It’s no wonder the Royals shipped him to the Mets following his rookie year in ‘86. He maintained those mechanics and developed into a five-time World Series champion, a Cy Young Award winner and, at least, a borderline Hall of Famer. Cone went 194-126 (.606 winning percentage) with a 3.46 ERA during his 17 seasons. If advanced metrics are more your style, he posted a lifetime 62.3 WAR, less than a full win behind Hall of Famer Juan Marichal, and a 121 ERA+, the same as Cooperstown inductee Don Drysdale.

Technically, Cone had four pitches—fastball, slider, splitter, curveball. But he had different versions of each of those pitches, giving him at least eight different options to go to before even factoring in location. And when he was at his best, he was comfortable throwing all of them in any situation.

“He was one of the most creative pitchers I ever caught because of all the different arm angles that he could throw from with his four-pitch mix,” says Joe Girardi, Cone’s catcher with the Yankees from 1996-99.

Not all pitchers can do this. It was Cone’s great advantage, but also so complex that getting one part of his windup wrong could disrupt the rhythm and timing essential to pitching.

Cone’s favorite putaway pitch was his signature “Laredo” slider, named by Mets teammate Keith Hernandez because of how Cone would drop his arm and throw it from below his belt, “down south” like Laredo, Tx. He developed the “Laredo” by watching his idol Luis Tiant, who won 229 games in his 19-year career and used his wipeout slider and funky delivery to become one the most deceptive pitchers of his era. Cone describes Tiant as a “pitching contortionist,” and as a boy Cone would sit on the floor close to the television to study El Tiante more closely.

But there was also something about Tiant that could not be replicated. He had this presence on the mound that was inimitable, and it absolutely “enamored” Cone.

“When I was coming up, a 10- 11- 12-year-old, it was all about style and flamboyance and attitude on the mound,” Cone says. “Max Scherzer is one of the most intense people on the mound, and he is all about attitude. He is all about presence on the mound. That’s the human element, and that will never go away.”

Over the course of his career, Cone shaped his own distinct style, flamboyance and attitude on the mound by studying guys that came before him, like Tiant and Seaver, and observing his peers. Cone’s motion derived from Seaver, with his father's tutelage. From Ron Darling, his rotation mate with the Mets, Cone learned to keep throwing his splitter even when it wasn't effective, because he wasn't going to fix it by not throwing it. This taught him to make adjustments on the fly and regain a feel for his malfunctioning pitches mid-game.

Still, there was something about Cone on the mound that was innate, traits that he exhibited that were distinctly him.

“When he’s on the field, there’s this vein that starts to protrude out of the side of his neck and one big one in his forehead,” Kay says. “He almost becomes maniacal.”

The bulging veins were classic Cone, a Hulk-like feature on an otherwise ordinary looking pitcher. His intimidation factors were limited to those veins and the mid-90s fastball he could hum in there during his prime—hardly physically imposing in a league with Randy Johnson and Roger Clemens.

At the same time, though, Cone’s attack could be more scarring. Hitters knew what to expect, and fear, from Clemens and Johnson. When Cone was in kill mode, he had more weapons in his arsenal than hitters could monitor. They’re what gave him staying power in the big leagues, even after his velocity had faded and when one or two pitches in his repertoire were ineffective. He always had somewhere else to turn.

Cone prepares for a broadcast with the same focus he did for each start. He still arrives three hours before first pitch, but rarely does he go fishing for information in the clubhouse with the rest of the press during pregame media availability. It’s definitely a role reversal. During his playing days, he was often the one chatting it up with the beat writers, never one to shy away from a conversation. He’d even breeze through a few short interviews before games he was pitching—a big no-no for almost every starter.

Instead, he peruses the latest headlines to catch up on anything he might have missed from previous day’s games, and he looks at some of the leading analytical websites for information he can use on the air.

“It all starts with me wanting to be current and wanting to understand the changes in the game and get versed on them,” Cone says. “It doesn’t look like he has his curveball tonight, or he’s really struggling with this pitch, and then to back it up with something from Baseball Savant. Oh, by the way, his spin rate is down a little bit. So what I’m seeing with my eyes I can verify for you.”

It’s one thing for an analyst to embrace Statcast data and understand how to incorporate spin rates, exit velocities and launch angles; that’s hardly uncommon in today’s media landscape. However, it’s quite remarkable when the broadcaster educating fans is a former Cy Young Award winner who lived through the days of pitching through fatigue and, sometimes, legitimate pain.

“You have to keep it on a boiler-plate level at first,” Cone says. “I guess the old saying is if you can’t explain it concisely then you probably don’t understand it well enough yourself, so you should probably stay away from it. That’s kinda my motto.”

When Cone pitched, it was a failure not to face a team the third time through the order. Now, it’s regularly recommended to remove a starter if and when he goes that deep in a game. Remember, this is the same guy who recklessly ignored his deadening arm in Game 5 of the ‘95 ALDS, walked in the tying run on his 147th pitch and ultimately needed surgery to remove an aneurysm found under his right armpit that nearly ended his career.

In ensuing seasons—like in Game 3 of the ‘96 World Series when he famously lied to manager Joe Torre to finish the inning—Cone still toed the line between responsibly working through fatigue and dangerously pitching through pain. But, he began to realize that his macho, go-until-you-blow mentality on the mound might not be best.

Instead of “poo-pooing” something that seems foreign, Cone says, “I always felt a need to educate myself before I criticize it.” This became his reputation as he developed as a pitcher, and it’s stayed with him now as a broadcaster.

“I think he’s turned himself into the best analyst in baseball, and that’s including the national guys, no disrespect to them,” Kay says. “He’s old school and new school all at once, which is hard to do.”

Look no further than to Cone’s Twitter feed from that very same Friday night in Kansas City to understand just how hip this 56-year-old can be.

The game began in a rain delay and was soon postponed till the next afternoon. To pass the time, Cone went on a massive following spree. He obliged nearly everyone who tweeted @dcone36 and asked for a follow that night and throughout the weekend. And in his own man-of-the-people way, he even crafted personalized responses to each follow request.

“I’m sorry #YankeesTwitter I thought I was on Tinder,” Cone wrote on Twitter. “I just kept swiping.”

And people just kept following.

Cone may have the credentials to be a successful pitching coach in today’s game, and he’d certainly be open to working with analytic departments, but it’s not a path he’s interested in taking right now. But he hasn’t ruled it out entirely.

“I would never say never,” Cone says about coaching. “I’ve thought about it a couple of times. I was asked a couple of times to interview. Just wasn’t ready to make that commitment. Coaching has never been harder. Those guys—relative to the money in the game—don’t make a fair amount, in my mind. The hours after the game they have to spend on video and all the analytics and frames of data they have to be versed in. It’s never been harder to be a pitching coach.”

This reluctance hasn’t stopped his name from floating around in the rumor mill for managerial job openings. He was reportedly in the running to replace Girardi as the Yankees manager after the 2017 campaign, and with Mets skipper Mickey Callaway seemingly always on the hot seat, Cone is regularly brought up when potential candidates are discussed.

Those who interact with Cone on a daily basis agree that he’s got it too good right now to commit to the pitching coach’s lifestyle. But they say it wouldn’t be at all surprising if he decides to manage one day, even if he doesn’t know he wants to do it yet.

“I absolutely think he has the knowledge and the intelligence to do that if he ever chose to do it,” says Jack Curry, who covered Cone for years on the Yankees beat in addition to being his YES co-worker and Full Count co-author. “I think he really enjoys what he’s doing right now. But there are times in the booth where, without a doubt, on a nightly basis he sounds like a manager or a pitching coach to me.”

Two successful managers in their own right, Girardi and Torre, agree that Cone has all the qualities of a great manager.

“He’d be a great manager because people would respect him and he would protect his people and he would run through a wall for them,” Kay says. “I think he craves being in uniform. And this is just from being around him a lot. I see the way he adores the game. He just loves it.”

Cone still dreams about pitching, about staring in for the catcher’s sign until getting the one he wants, dropping down and unnerving batters with his Laredo. Those dreams feature all the complex emotions that made him one of the toughest pitchers to figure out through the course of his career. There’s the cocky Kansas City gunslinger, whose adrenaline highs were just as potent as the lonely doubts of long nights on the road. There’s the ultra-competitive maniacal man, protruding veins and all, who, as Torre once told Kay, would “really kill somebody to get somebody out.”

All of that is behind him now, the memories contained to game footage, books and news stories.

But he remains the academic who studies pitchcraft as if it were a master’s class. He’s still adapting to the ever-changing game he loves.