What Happened to the Houston Astros' Hacker?

This story appears in the Oct. 8, 2018, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.

Illustrationsby Lincoln Agnew.

As the 2017 spring season wore on, it became increasingly difficult to score against one of the four clubs in the softball league at the federal prison camp in Cumberland, Md. The Dogs played the standard 10 fielders, but it seemed as if they had twice as many. Righthanded sluggers found the blasts that used to clear the outfielders' heads and the hard line drives that once sliced into gaps were gobbled up by the Dogs' strange defensive alignment, a triangular flytrap of three leftfielders: two of them deep and another shallow, behind the shortstop. The slap-and-dashers who tried to poke the ball the other way couldn't find any holes either. Against them, the Dogs stationed three infielders between first and second base. After each at bat, frustrated opponents noticed, the Dogs' coach scribbled notes on his lineup card.

The Dogs went undefeated, consistently thrashing even the powerful All-Blacks. Something to put on my résumé, the Dogs' coach thought to himself, mordantly. FPC Cumberland championship softball coach. His CV had once been impeccable. He had been Chris Correa, the former doctoral student who had steadily ascended through the front office of the Cardinals to become their scouting director, in charge of their amateur draft. No longer. Now he was Christopher J. Correa, federal inmate 04550-479.

Correa, 38, spent much of his time out on Cumberland's softball field even when there were no games. He walked laps around its perimeter for one to two and a half hours each day, covering four to 10 miles. He began to shrink inside his prison-issued dark green uniform, losing 35 pounds off his 5'11" frame, and his wedding ring dangled from his slimmed finger.

As he walked, he listened to a transistor radio. The NPR affiliates served mostly as background for his thoughts, which always cycled back to one simple question.

Why am I here?

Even after all those hours of reflection over all those miles, Correa can't recall the exact moment when his life veered off course. It wasn't in July 2016, when U.S. District Court Judge Lynn Hughes sentenced him to 46 months in federal prison. Nor was it seven months before that, when Correa pleaded guilty to five counts of unauthorized access to a protected computer after his extensive and prolonged breach of the internal database of the Astros, whose front office included several former colleagues whom he'd once counted as friends.

He remembered those moments very well. The instant that eluded him was the one that redirected his life from St. Louis to Cumberland: the first time he typed the password of Sig Mejdal, his former fellow analyst with the Cardinals, into the Astros' webmail system.

It was sometime after Mejdal and Jeff Luhnow left the St. Louis front office in the winter of 2011 to become, respectively, Houston's director of decision sciences and general manager. Was Correa at his Busch Stadium office when he hacked into the Astros' system, if you could even call what he did hacking? Was he at home? On the road? Typing a password was just so forgettably easy, disconnected from real life, real people and especially any real criminality, which he thought required the intent to cause harm. He guessed the password—Mejdal hadn't changed it more than a few keystrokes from the one he'd used on his old Cardinals laptop—and he typed it in. Then he typed it in again and again and again, pushing ever further into the wilderness.

Since he couldn't remember that first transgression, he tried to reconstruct all that led up to it. Correa grew up happy across the New Hampshire border from the manufacturing town of Lowell, Mass.; his father worked as a schoolteacher, and his mother as a nurse. Like many boys in New England, his best memories centered upon Fenway Park—especially when the Twins and his hero, centerfielder Kirby Puckett, came to town. His family's seats were in the rightfield stands, which were fine by Correa, as they were close to Kirby.

In the early 1990s, when he was 11 or 12, Correa's parents brought home his family's first home computer, a Wang. He quickly perceived the machine as more than an end in itself, but as a tool. He taught himself BASIC, and programmed it to play a tinkling version of "A Whole New World," from Aladdin, delighting his younger sister. At Pelham (N.H.) High he programmed puzzle games on his TI-82 calculator to amuse himself during classes, which often came easy.

Correa earned a degree in cognitive sciences from Hampshire College, the progressive liberal arts school in West Amherst, Mass., that allows students to design their own curricula; he focused on how people learn music. In 2004, he enrolled in a doctoral program at Michigan that combined education and psychology, studying how people learn not just music, but any discipline.

He realized that his years of tinkering with computers and all the programming languages he had informally learned could be put to powerful use in his research. He worked on studies that used eye-tracking technology to monitor students' attention during their lessons. He wrote software that could collect and analyze large-scale data sets, such as survey results. In 2007, he saw an Internet post soliciting bids to conduct a research project for the Cardinals. Because it sounded fun, he knew he could do it and, considering that he loved baseball, he offered to do it for free.

The project involved designing software that could scrape play-by-play data from the websites of college teams across the country, even those in Division II and Division III, and to centralize it, giving the Cardinals' burgeoning analytics department a resource that most of their rivals didn't have.

Correa nailed it. Another freelance project followed, and in 2009, when he had completed all of the requirements for his Ph.D. except his dissertation, the Cardinals offered him a full-time job. He took what was supposed to be a one-year leave from Michigan. "To see if I liked it," he says. "And I did. And I kept doing it. Until I didn't."

He accepted everything the Cardinals threw at him. He worked on the draft under Luhnow and Mejdal; his research into lower level college programs helped them unearth Slippery Rock's Matt Adams in the 23rd round in 2009, although they missed on Yan Gomes of Barry University that same year. He contributed to projects that helped St. Louis analyze pitchers' biomechanics, trying to find those likeliest to sustain injuries.

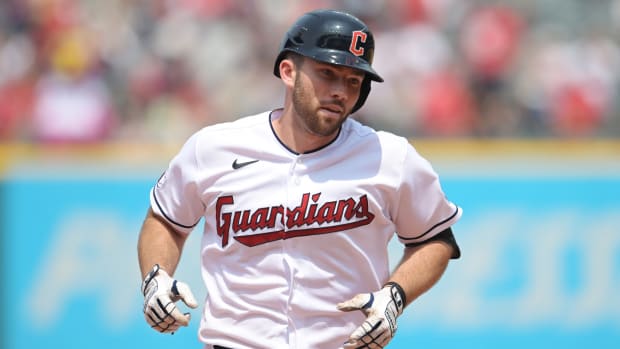

He loved the work. It was both collaborative and competitive in ways that even the most cutthroat of academic environments weren't. His work—his team's work—had real, measurable successes and failures, such as when Adams eventually became the Cardinals' cleanup hitter, or when Gomes turned into a starting catcher with the Indians.

Then Luhnow and Mejdal left for Houston.

Correa stayed behind in St. Louis. His old coworkers became the competition—and, perhaps most significantly to him, he suspected they weren't intending to play fair. He believed Luhnow and Mejdal had taken proprietary data and algorithms with them, which he and his colleagues had spent thousands of hours to help develop. On the fateful, unremembered day on which he first pecked Mejdal's old password into the Astros' email server—where he found more passwords that gave him unfettered access to Houston's new database—he believed he found evidence of his suspicions.

Over the next several years, Correa insists that he found more and more evidence, although he will not specify what that was. While he knew what he was doing wasn't right, he never thought that it could be a crime. "It was all in the context of a game, to me," he says. "When a pitcher throws at a batter's chest, nobody runs to the local authorities and tries to file an assault charge. I'm not making excuses. I'm trying to explain where my head was at, as I now understand it. If another team does something wrong, you retaliate. That's the lens through which I mistakenly viewed it, and I used that to give myself permission. It was wrong."

There is another theory to explain Correa's actions. It is that even if his intrusions came from a feeling that the Cardinals had themselves been violated, he used that to justify behavior that turned into something like a compulsion, rooted in both voyeurism and the fact that the information he acquired by illicitly peering into a chief rival's brain—and seeing the basis for every decision it made—provided an undeniable advantage to both the Cardinals and his own career. Investigators later documented that he had accessed the Astros' database at least 48 times, although he had almost certainly done so much more often than that. He had absorbed their draft rankings, their scouting reports and notes on their trade discussions, sometimes for nearly two hours at a time, and almost always took pains to digitally mask his activities. In December 2014, the Cardinals named the former freelance analyst as their scouting director—Luhnow's old gig.

When the Astros' internal trade talk notes appeared on the website Deadspin in June 2014—a leak the feds later attributed to Correa, who perhaps intended to embarrass his old colleagues—and Correa read that the FBI had become involved, he still didn't view what he had done as more than high-tech sign stealing, certainly not a crime. It didn't register as one seven months later, when he was about to take an early morning shower in the St. Louis home he shared with his wife, before going out on his first trip of the scouting season, and heard a loud banging at the front door. It was only after the agents began questioning him that he realized he wasn't going on that scouting trip, and that he needed a lawyer.

Correa's guilty plea came on Jan. 8, 2016, seven months after he'd run his first draft for the Cardinals—he picked outfielder Harrison Bader, pitcher Jordan Hicks and shortstop Paul DeJong, all of whom are now on the St. Louis roster—and six months after the club fired him. He signed a document stating that he could be sentenced to up to five years in prison and that he had caused $1.7 million worth of losses to the Astros. That figure, conjured by the government, was necessarily fuzzy, as it was impossible to know the financial damages resulting from the information he had obtained.

He and his lawyer, David Adler, agreed to the plea deal for two reasons: "One, I was guilty. Two, I wanted to accept responsibility as soon as possible so I could move on with my life, whatever that meant." If he lost at trial, his incarceration could have lasted so long that he and his wife, whom he married in 2009, might not have been able to start a family after his release.

The Astros have always denied having themselves taken anything inappropriate—anything more than what talented employees always possess when they move from one company to another—and asserted that data from 2011 would have become quickly outdated anyway, certainly long before '14. They were the only victims.

Both the prosecution and Judge Hughes agreed.

"You broke into their house to find out if they were stealing your stuff?" an incredulous Hughes asked Correa.

"Stupid, I know," Correa said.

Correa returned to Hughes's courtroom on July 18 for sentencing. "The whole episode represents the worst thing I've done in my life by far, and I am overwhelmed with remorse and regret," he told the judge.

Hughes seemed unmoved. He sentenced Correa to his 46 months—a term based in part upon the $1.7 million that the government estimated he had cost the Astros—and ordered him to pay $279,038 in restitution. Even some Houston executives were stunned by the magnitude of his sentence, but prosecutors reveled in their high-profile victory. "This is a serious federal crime," U.S. Attorney Kenneth Magidson told the media. "It involves computer crime, cybercrime. We in the U.S. Attorney's office look to all crimes that are being committed by computers to gain an unfair advantage .... This is a very serious offense, and obviously the court saw it as well."

Really? thought Correa. I'm the big criminal mastermind you're proud to nab? Even so, he found some comfort in finally knowing what his future held. "Having the ability to say, 'O.K., I'm going to do my time, I'll get out in 2019 or whatever and then come up with a plan for rebuilding my life,' that's actually a relief," he says.

In the near term, though, Correa had to start reckoning with what his life had become. A few years before he'd been a doctoral student with a lingering boyhood affection for baseball. Now it was time to report to federal prison.

What do you do on the day before you go to jail? Correa went to the dentist. He had heard that prison dentists don't offer to fill decayed teeth with your choice of amalgam, gold, or porcelain. They just pull them. And he had a cavity. "Can we schedule another appointment for six months from now?" the receptionist asked him.

"I'm going to be out of town for a while," Correa said.

In the six weeks between his sentencing and Aug. 30, 2016, when he was due to report to Cumberland, Correa spent a lot of time ensuring that his wife had everything she required to run their affairs without him: access to all their accounts, power of attorney, the ability to continue to pay down his student loans. He visited friends and family in New England until the day drew near and the goodbyes became too painful. On the drive to Cumberland, in the northwest corner of Maryland, he and his family sat mostly in silence as the cruelly beautiful Allegheny Mountains approached. It felt as if they were driving him to his own funeral.

His first days brought many surprises. The Federal Bureau of Prisons operates, essentially, four types of facilities, categorized by security level. The main facility at Cumberland is a medium-security prison—the second-highest level. It is surrounded by razor wire; it is violent; many of its 950 or so inmates make license plates.

• Find more Sports Illustrated True Crime stories here

Correa, though, was assigned to Cumberland's minimum-security satellite camp, which houses around 250 men. From the outside, it looks like a dormitory at a badly underfunded state university. There are no fences and no bars on the windows. The showers are private and safe. At night, there is often a single guard on duty. An inmate can easily simply walk away if he so chooses, although that almost never happens. If he were at all likely to abscond, or to commit violence—based upon a scoring system, called SENTRY, that takes into account such factors as the nature of his offense, his education, and whether he's a member of a "disruptive group" like the Aryan Brotherhood—then he would not be designated to a place like the satellite camp. Past inmates have included Bernard Kerik, the former New York City police commissioner who pleaded guilty to tax evasion, and Jack Abramoff, the powerful lobbyist who pleaded guilty to fraud, tax evasion and conspiracy to bribe public officials.

The biggest shock to Correa, though, was that the camp provided him and his fellow inmates with almost no guidance on how to spend their time. Correa had always viewed prison as a method to punish those who had committed offenses against society, but also as a place where they might be equipped with skills they would need to avoid a recurrence of their past behaviors when they were ready to rejoin it. At Cumberland, there was little direction, just a lot of lying around. "I think the focus on punishment and custody versus rehabilitation is a surprise to a lot of people," he says. "I think a lot of people are surprised that it's more or less just a warehouse for people."

He got to know his fellow inmates. Most of them were not wealthy nor white; as of August, whites accounted for just over one-third of the camp's inmates. Many of them had become ensnared by either trafficking or using opiates, and all of them had been deemed no threat to society. His central question expanded: Why are all of us here?

Jack Donson is a former federal prison correctional treatment specialist who now works as a prison consultant and reformer. To him, the unexpected dynamic that Correa perceived is a result of the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 and subsequent legislation which abolished federal parole and established mandatory minimum sentences by creating the U.S. sentencing guidelines. Now, despite having just 5% of the world's population, the United States has a quarter of the world's incarcerated people—far more than its prison system is equipped to productively deal with—and its vast criminal justice system costs more than $270 billion a year, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Since the '80s, the federal prison population has increased by 600%.

"They switched from a paradigm of treatment and rehabilitation in the '60s and '70s to mostly punitive in the '80s," Donson says. "In the minimum security facilities, especially, there are limited resources. Almost no medical staff, almost no education staff. These guys are basically left to fend for themselves."

The only daily structure Correa found revolved around mealtimes—breakfast at 6, lunch at 10:45, dinner at 4:15—and the times when the inmates were counted. So he developed a routine to fill the rest of his days. He took his walks. He coached softball—and he refereed basketball, too, until he thought better of it after a few players angrily overturned the scorer's table. "I don't recommend reffing prison basketball for anyone," he says. He taught himself to play guitar.

When he first arrived at Cumberland, he was given size 42 uniform pants and a tiny, thin T-shirt, so he had to shuffle around holding the pants up at the waist and shivering in the facility's air conditioning. Another inmate offered him a sweatshirt. "There were a lot of good people who try to look out for each other," he says. He resolved to become one of them. Because of his academic background, he eventually became the camp's continuing education coordinator, which mostly meant that he oversaw the library and the classes that inmates taught each other. Half of his wages, which ranged between 12 and 40 cents per hour, were garnished by the Astros at the order of Judge Hughes.

That work detail only took a couple of hours a day, so he organized mock job fairs, helped inmates craft résumés, and became the go-to guy if you needed help figuring out how to apply and pay for any sort of document: a birth certificate, a social security card, a credit report. "Anything that could help remove one more obstacle to rebuilding a life," he says.

In the evenings he returned to the nine foot by eight foot room—called a cube, not a cell, because it has no door—that he shared with three other inmates, as well as a dog who one of them was training as part of one of the only formal programs that the Cumberland camp runs. (The program inspired the softball team's name.) His cubemates were an engineer, a property manager and a financial manager, each in his 40s or 50s; more than 50% of the Cumberland camp's inmates are older than 45. They sat on their two-feet-wide bunk beds and joked and talked. "You try to help each other make the time go," says Correa. "You can either laugh or you can cry."

After the 10 o'clock head count, he would jump back into bed and begin to read. He consumed nonfiction related to science and technology and current events, as well as the entire oeuvre of Cormac McCarthy. He read one page of the dictionary, back and front, every day; it took a year and a half. For many inmates, the loneliness of nights in prison is torturous, but Correa looked forward to them. I've completed another day with my dignity, my sanity, he told himself.

In some ways, Correa felt lucky. His wife stayed married to him. He had no children to miss. He consistently received visitors—not every weekend, but often enough. He always used up his 300 monthly phone minutes. The pain of not being there for grandfather's funeral and for the birth of his sister's child would always gnaw at him, but still he was able to maintain enough of a support structure to allow him to avoid feeling hopeless.

A loss of connection was, for many, insidious. Like a lot of prisons, Cumberland is located far from any major population center or airport; it's about a 2½-hour drive from each of Baltimore, Pittsburgh, and Washington D.C. The cost and time required to visit loved ones in prison is too much for many families. Correa saw how inmates on sentences longer than his received hardly any visitors. One friend, in on a 12-year stretch, told him how when he entered prison, he'd always run out of his phone minutes early each month. Then he stopped running out quite so soon. Eventually, he stopped running out of them at all.

"I just think we're fomenting recidivism," Correa says. "It doesn't make a lot of sense, to see it firsthand. You see people with their hearts in the right place, trying to do the right thing, but they're nervous about going back home because they no longer know anyone and don't know how to do anything except maybe what got them here—sell drugs, or whatever." It's not cheap, either; even minimum security inmates cost taxpayers around $24,000 per year.

Another answer as to why Correa was in Cumberland: the wheels of criminal justice reform turn glacially slowly, and in many important ways American offenders are stuck in a Reagan-era prison-industrial complex. Correa helped his fellow inmates when he could. But most of the time, instead of using his talents for a broader purpose, he just sat there, warehoused, trying to fill each day until the next one came.

None of the other inmates in Cumberland knew about Correa's background—or that he was the camp's most prominent resident—until Jan. 30, 2017. That was when baseball commissioner Rob Manfred levied a $2 million fine on the Cardinals for Correa's actions, ordered the club to surrender two draft picks to the Astros and banned Correa from the game for life. Inmates in Cumberland are not allowed to access the Internet, but it was on the news. "Was that you?" people asked him. "Yeah, that was me," he said.

Nine months later, when the Astros won the World Series, he didn't feel much of anything. "I'm happy for those guys, but obviously it's kind of a mixed history with the organization," he says. "Not happy about the way they went about some things, but I'm not resentful." (Says Astros general counsel Giles Kibbe: "We have always maintained that the Astros did nothing improper. The FBI and MLB have both extensively looked into Mr. Correa's actions. Neither have said that the Astros did anything improper. What is clear from the proven facts is that Mr. Correa unlawfully intruded into our system.")

Correa felt he had moved past rancor toward not only the Astros but also Major League Baseball, and even St. Louis. While it has always been difficult to believe that no one else within the Cardinals at least knew what Correa had been up to, investigators didn't identify a co-conspirator, and only Correa was individually punished. ("The breach of the Astros' database was thoroughly investigated by the FBI, by Major League Baseball and through our own internal investigation," says Mike Whittle, the Cardinals' general counsel. "All three of those investigations concluded that the breach of the Astros' database was isolated to a single individual.") But Correa no longer has the desire to relitigate who had done what. "What I've endured, I'm not going to wish on anyone," he says. "Nobody I know is a bad enough person."

He didn't watch an inning of the Astros' championship run, for a few reasons. "There are TVs, but the population is young and diverse, which is not exactly baseball's key demographic," Correa says. "I'm not going to fight to change the channel." As someone who had regularly stood close enough to the cage at Busch Stadium to hear bats whistle, he found it unsatisfying to follow the game through newspaper box scores and periodic updates from friends.

Correa has also narrowed his focuses to the things that really matter to him. Even though pro baseball isn't among them he still wants to reach a deeper understanding of why he acted as he did when he worked in the game. He has thought a lot about Immanuel Kant's categorial imperative, which removes context from any assessment of moral obligation; what's wrong is always wrong, no matter the circumstances. "What was really surreal to me was when I stood back and recognized how essentially disrespectful my behavior was of the people whose privacy I violated," Correa says.

He stops short of imagining precisely what his future might look like. He has considered resuming his doctoral studies, but under terms of his plea bargain he is expected to find a job to continue to pay off the nearly $280,000 he owes the Astros—a challenge for any convicted felon, even one with Correa's intelligence and experience. He would like to figure out a way to direct his skills, particularly in education and data analysis, to reforming a criminal justice system he now knows from the inside.

"Applying my skill set to baseball was interesting in a lot of ways, but probably one of the more unsatisfying parts of it is that baseball's a zero sum game," he says. "If I did my job really well, all that meant is I helped my team win a few more games, and that some other team lost some games. I'm not really adding a lot. If I were to apply some of my skills to a civic-minded organization, that would be an opportunity to actually contribute something positive to the world without necessarily taking something from someone else."

Everyone in baseball has now moved on from him, anyway. The Astros are embarking upon their second consecutive postseason, and the Cardinals narrowly missed the playoffs. Correa himself will move forward sooner than he once expected. Due to a combination of good behavior and programming, his 46-month sentence has been reduced. On July 5th he was transferred to a halfway house in Washington. He is now on home confinement, which means that he spends nights at home, with his wife, but must otherwise be at the halfway house or at his job—a temp position in which he performs administrative office work for 40 hours a week. If all goes right, he will receive his supervised release on Dec. 31. Like every inmate, he will have to persuade society not to define him by the worst thing he ever did.

"Every day I'm getting closer," he says. "I hope someone's willing to give me a chance."