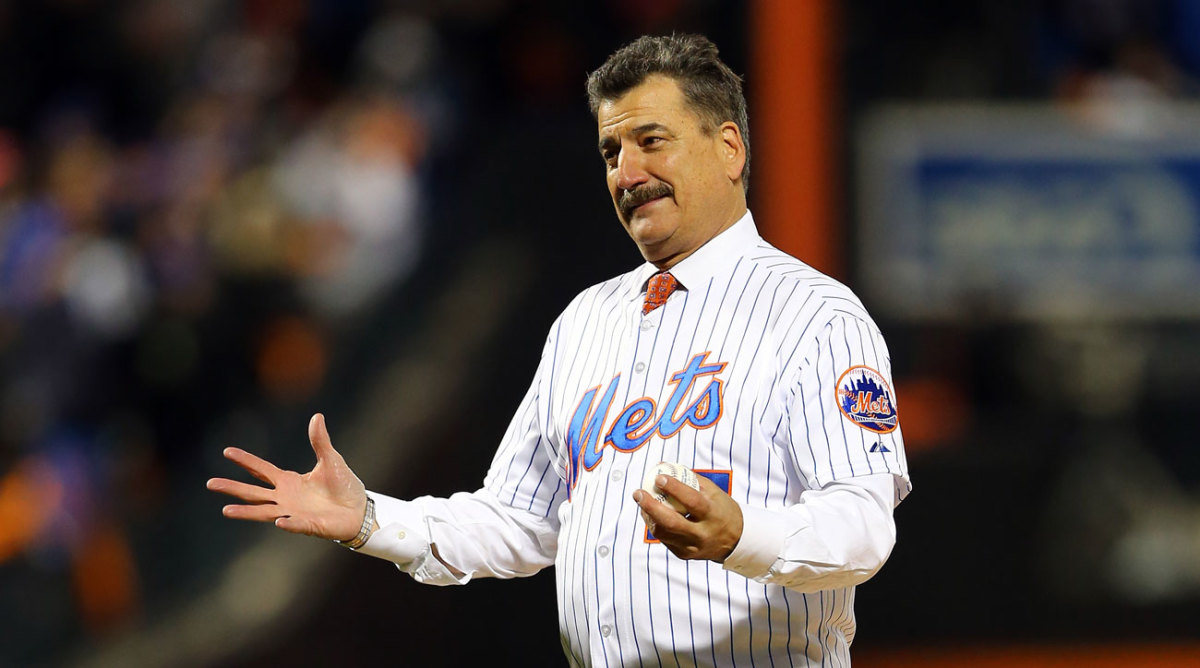

Keith Hernandez, Lou Piniella Focus on Humanity, Not Glory, in New Memoirs

When Keith Hernandez was nine years old in Pacifica, Calif., he attended his first major league baseball game, in San Francisco, where he saw a Cardinal warming up with his cap off. He had never seen a big leaguer without a hat. Not on baseball cards, not on the NBC Game of the Week, not in the vivid daydreams Hernandez entertained while bouncing a ball against a brick wall of his house. "My heroes lived mostly in my head," concedes Hernandez, who couldn't reconcile this St. Louis shortstop's greatness with this St. Louis shortstop's ... baldness. Young Keith never forgot that summer day in 1963, or the astonishing spectacle that greeted him at Candlestick Park: "Dick Groat's bald head, glistening in the California sun."

Three decades later Hernandez got another peek behind the curtain of a world whose glamour exists primarily in our heads. He attended a screening of Lawrence of Arabia at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York City and afterward met its star, Peter O'Toole, at Elaine's, the Upper East Side watering hole of the beautiful people. Hernandez was now one of those people, after his glittering career in the big leagues, and he asked O'Toole what he thought of the epic film, which won Best Picture in 1963. The eight-time Oscar nominee replied that he'd never actually seen Lawrence of Arabia. But, O'Toole said, "I hated those f------ camels. It was so hard on my ass."

Elaine Kaufman, proprietor of Elaine's, eventually told Hernandez to get off his own ass and do something other than drink wine in her restaurant, years after he retired following 17 major league seasons. But Kaufman isn't even the most famous Elaine in Keith's life, for he famously dated Elaine Benes on a timeless episode of Seinfeld. While that Elaine was kissing him, her interior voice asked with an air of wonder, "Who does this guy think he is?" To which Keith's own inner monologue replied, equally impressed, "I'm Keith Hernandez."

The charming self-regard of Keith Hernandez is evident in the title of I'm Keith Hernandez, his poignant, unexpectedly literary new memoir. He calls himself "Keither" on one occasion, but he's otherwise eager to strip his career of ego and glamour. Hernandez scarcely mentions his Mets years at all, writing instead of his struggle to establish himself as an everyday big leaguer. And so he learns to sleep "like a vampire," arms crossed over his chest, in the luggage racks of buses on epic minor league road trips. He becomes expert at "ignoring sexual intercourse occurring only a few yards away" while rooming with teammates in seedy motels. He is counseled by pitcher Dick Selma to drink Scotch and soda because it's "hydrating"—and management can't smell it on your breath.

Of all these baseball dark arts, the darkest by far is this: Hernandez must learn—across acres of anxiety and oceans of self-doubt—to hit lefthanded pitching. For many years this becomes the great struggle of his life, made even more difficult in dumps like the Astrodome, whose shadowy centerfield depths—bereft of a batter's eye backdrop—he compares to the "ancient mines of Moria" in Tolkien's Middle-earth.

Because the author's struggle happened from 1972 (when he was an 18-year-old minor leaguer) to '79 (when he abruptly arrived, batting .344 and being named co-MVP of the National League), I'm Keith Hernandez is also a visceral distillation of the 1970s. When Keith drives his burgundy Monte Carlo from St. Louis to San Francisco after the '75 season, stopping in Denver at a "meat market" called The Loft, where he picks up a "hippieish brunette" whose filthy bed gives him scabies, for which he is prescribed Kwell shampoo ... well, you can practically smell the Brut by Fabergé.

As a child of the 1970s who moved to New York City in the '80s to work at Sports Illustrated, I spent my first sweltering summer in an apartment on East 48th Street. The town house next door belonged to Kurt Vonnegut; a block north I might run into Katharine Hepburn; and around the corner, in that high-rise on Second Avenue, lived the greatest of them all: first baseman Keith Hernandez, one full season removed from the Mets' 1986 World Series victory. It wasn't long before I saw Hernandez at Gristedes, the corner supermarket. The same cognitive dissonance he felt seeing Dick Groat bald, I felt seeing Keith Hernandez buy eggs.

Twice divorced, Hernandez and his 15-year-old Bengal cat Hadji now spend their summers in Sag Harbor, N.Y., for he—Keith, not Hadji—has been a popular and discursive Mets color commentator on SNY ever since Elaine Kaufman scolded him. Hernandez spends winters in South Florida, where he has the same experience with athletes at Publix as I did with him at Gristedes. "It's kind of like Disneyland," he writes of the countless retired ballplayers living nearby. "All these characters from the sport's yesteryear walking around. And they all shop at Publix."

His first glimpse of Florida came when he arrived for his inaugural Cardinals camp as a highly touted 42nd-round draft pick, and if that sounds like an oxymoron, Keither explains that he didn't play in his senior year of high school because "my high school coach was a bit of a jerk." When he arrived in St. Petersburg, at 18, young Keith searched his bag for his Strat-O-Matic cards and dice, for he was playing the entire 1971 season of that baseball simulation game, for every single big league team. Only on arrival in camp did he notice that his fireman father in Pacifica had slipped the Strat-O-Matic out of his son's suitcase, later telling Keith over the phone, "You gotta concentrate on real baseball."

But what is "real baseball"? What you watch and what big leaguers play are two very different things. You don't see 18-year-old Keith, after two errors and merciless heckling from half a dozen college kids, break down and sob in his Class A manager's office. "Oh, Jesus," replied Roy Majtyka, a cigarette dangling from his mouth.

****

Which leads us us, neatly, to another smoking skipper, this one far more famous. On May 15, the same day Hernandez's memoir will be released, Lou Piniella's autobiography, written with Bill Madden, comes out in paperback (Lou: Fifty Years of Kicking Dirt, Playing Hard, and Winning Big in the Sweet Spot of Baseball). Here are two quintessential New York baseball figures whose playing careers overlapped by 11 seasons. Mex and Lou embodied the Mets and the Yankees, respectively—New York, New York.

Piniella, like Hernandez, had an outsize hold on my nascent career, for I became a baseball writer in 1990, the season Lou managed Cincinnati to a World Series sweep of the A's. That summer, I was around the Reds more than any other team, and I smuggled pitcher Jack Armstrong into Riverfront Stadium in my rental car. Armstrong was an hour late to work on a Sunday morning, and when we saw Piniella outside the clubhouse door, smoking and gazing contemplatively into the middle distance, Armstrong ducked under the dashboard and instructed me to drive on. Piniella, who was occasionally terrifying and frequently temperamental, also had an endearing sense of humor. When he went to the mound to remove Ted Lilly in the fourth inning of a Cubs game, the lefthander said, "What're you doing out here? Selling hot dogs?" The skipper looked down to see his fly was open and struggled to stifle his smile.

Jeff Pearlman, a successor on SI's baseball beat, once interviewed Piniella while he simultaneously 1) smoked a cigarette, 2) ate a hoagie and 3) stood at a urinal, taking a leak. In Lou, Piniella tells his own hoagie story. His grandfather brought him Cuban sandwiches to eat before games when Lou played at the University of Tampa. But Grandpa arrived late once, just before the start of the second inning, and handed Lou the sandwich through the Cyclone fence. Piniella concealed it in his glove, praying the ball wouldn't be hit to him. But it was. Lou caught the fly ball in an explosion of deli meats and cheeses.

For aspirants to the big leagues, the stresses are ever-present and often unforeseeable. Piniella has his own stories about endless bus rides, including one with the Yankees during spring training, when the bus abruptly stopped at a South Florida convenience store. He loved his manager, Bob Lemon, whose red schnoz, Piniella writes, was "a telltale sign of his drinking." As the bus idled, and the Bombers silently wondered what they were doing here, third baseman Graig Nettles shouted from a backseat: "We have to get batteries for Lem's nose!"

The great pathos in Piniella's story comes from the premature deaths of his three best friends in baseball—Yankees greats Thurman Munson, Catfish Hunter and Bobby Murcer. There were lesser trials, of course, including the "doggie grams" Piniella received on the road, ostensibly from Schottzie, Reds owner Marge Schott's Saint Bernard, who wrote things like: "Doggone shame you lost."

Where Hernandez once struggled to hit lefties, the great conflict of Piniella's story arc is his volcanic temper. He uses the hyphenate "red-ass" 14 times in Lou, if you count the minor league manager in Elmira, N.Y., who told him, "You're never gonna play in the big leagues because you're too big of a red-ass!" That manager was the apoplectic Earl Weaver.

Of course, Piniella overcomes his own crimson cheeks to make it, but it's the climb, the struggle, the taxiing before takeoff that fascinates.

Indeed, Hernandez scarcely comprehends the interest in the famous version of himself. That Keither, he writes, you can "discover in a Google search." Signing a baseball card while entering Citi Field as a Mets broadcaster, he is asked by a middle-aged man, "You think the weather's gonna hold off?" Hernandez writes: "Why is it that people feel the need to fill in the three seconds it takes to sign an autograph with idle chitchat? I'm not complaining; it's just an observation, and I think it's hilarious. I mean, a grown man did just ask if another grown man could sign his baseball card."

What the autograph-seeker doesn't know, but Hernandez does—just by looking at his facial expression on that baseball card—is that he had grounded out to the right side of the infield on his 1984 Topps. This performance anxiety pervades I'm Keith Hernandez, and major league baseball generally, for careers can typically be divided into two eras: Getting the Job and Keeping the Job.

At one point Piniella refers to his former boss with the Yankees, George Steinbrenner, as "a royal pain in the ass," echoing Peter O'Toole's comment about his famous film. Both of these memoirs are useful reminders that our envy of big league ballplayers and other stars, while understandable, is often misplaced. You and I marveled at Keith and Lou in Lawrence of Arabia. But those two had to ride the f------ camels. It was, we know now, hard on the ass.