The Electrifying Vladimir Guerrero Presents a Strong, if Flawed, Case for Hall of Fame Induction

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2018 Hall of Fame ballot. Originally written for the 2017 election, it has been updated to reflect it has been updated to reflect recent voting results as well as additional research. For a detailed introduction to this year's ballot, please see here. For an introduction to JAWS, see here.

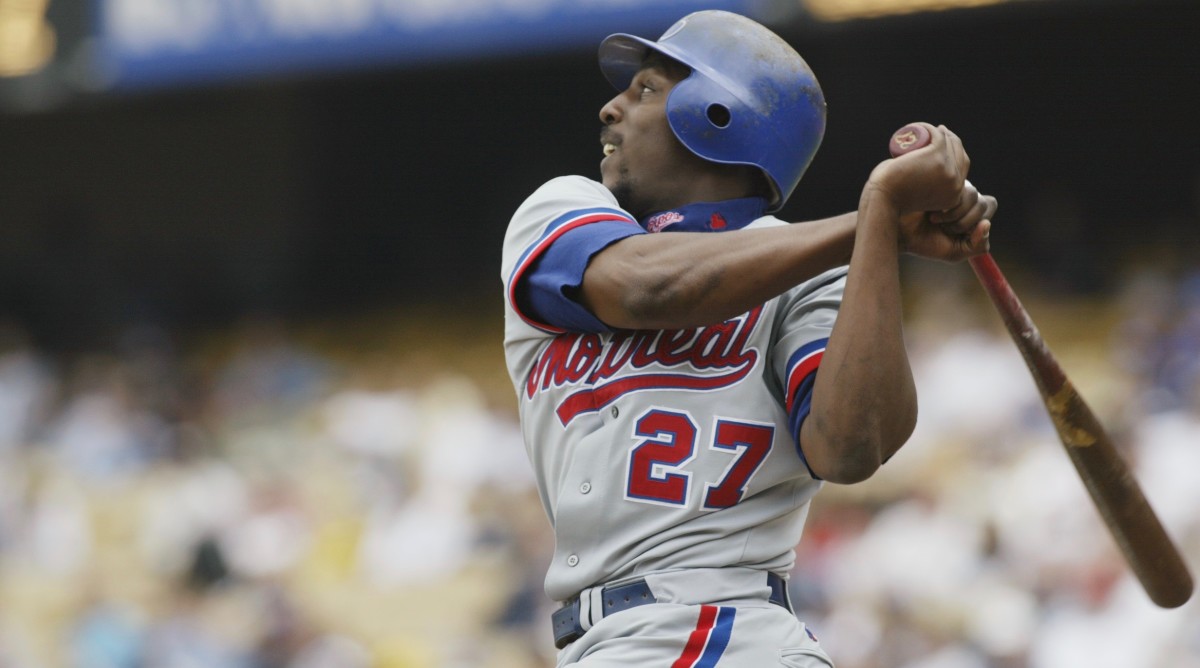

Vladimir Guerrero’s plan was simple: See the ball, hit the ball. Blessed with outstanding hand-eye coordination, he wasn’t afraid to swing at anything, from pitches that were over his head to those whistling through the lefthanded batter’s box at ankle height. Legend has it that he hit a home run on a pitch that bounced in front of the plate. Even if that is apocryphal, there is video evidence of him collecting hits on the bounce.

Guerrero grew up in dire poverty in the Dominican Republic and was a diamond in the rough with an unrefined skill set. He retained some of that lack of refinement throughout a 16-year-career spent primarily in Montreal and Anaheim, not only at the plate but also on the base paths, where he showed off blazing speed but also ran into outs, and in the outfield, where he never met a cutoff man he wouldn’t airmail in hopes of gunning down a runner. “He had hubris, and he had balls,” wrote Montreal native Jonah Keri in Up, Up, & Away, his 2015 history of the Expos. “That's what made him so much damn fun to watch, win or lose.”

Indeed, for as raw as Guerrero’s game remained, it was effective—and spectacular. The nine-time All-Star generally wound up among the league leaders in batting average and slugging percentage, had two seasons with at least 30 homers and 30 steals and won the 2004 American League MVP award by carrying the Angels into the playoffs almost singlehandedly. His case for the Hall of Fame is stronger on the traditional merits than the advanced ones, which wasn’t an impediment when he made his debut on last year’s crowded ballot. He fell just 15 votes short of election, receiving 71.7%, and shouldn’t have to wait too much longer to get his bronze plaque sooner or later.

Player | Career WAR | Peak WAR | JAWS | Hits | HR | SB | Avg/OBP/SLG | OPS+ |

Vladimir Guerrero | 59.3 | 50.2 | 50.2 | 2,590 | 449 | 230 | .318/.379/.553 | 140 |

Avg. HOF RF | 73.2 | 43.0 | 58.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Born in 1975 in Nizao Bani (about 45 minutes west of Santo Domingo), Guerrero was one of five children. The family lived in a shack with no electricity or running water, and after a hurricane blew its roof off, seven family members had to share two beds in a single room. When his mother, Altagracia Alvino, was three months pregnant with him, his father ran off. When Guerrero was six, his mother illegally snuck into Colombia and then Venezuela, sending paychecks from her work as a cook and a maid back home. As a child, Guerrero drank from puddles and missed so many classes while instead harvesting vegetables in the fields that he stopped going to school after fifth grade. His lack of education would later manifest itself as a painful shyness: “El Mudo” (the mute) never learned English and rarely gave interviews during his career.

All four Guererro boys wound up signing professional baseball contracts. Older brother Wilton signed with the Dodgers and wound up playing eight years in the majors (1996–2002, '04), four of them as Vlad’s teammate in Montreal. Another older brother, Eleazar, didn’t advance past the Dodgers’ Dominican academy, and younger brother Julio Cesar topped out with the Red Sox' Class A team after signing for a $750,000 bonus.

An (Re)Introduction to JAWS: The Formula to Help Determine Who Should Make the Hall of Fame

When Vlad was believed to be 16 (he claimed to have been born in 1976 until revealing the truth in 2009), he spent two four-week sessions trying out at Campo Las Palmas, the Dodgers’ academy. The Dodgers saw him as a slow, fat player with a long swing, and while he worked his way into shape via two-a-day practices, both they and the Rangers—who gave him a look at their academy as well—passed. In February 1993, Expos scout Fred Ferreira—known as “The Shark of the Caribbean”—invited him to a tryout that provided the first cornerstone of his legend. Vlad hitched a ride on the back of a friend’s motorcycle, showed up with a mismatched pair of spikes with a sock jammed into one that was too big and pulled a groin muscle while grounding out in his lone at-bat. Ferreira nonetheless signed him for $2,000 on the strength of a 60-yard dash time of 6.7 seconds and some strong throws.

Guerrero shot through the Expos’ system quickly, turning heads with his raw but exceptional tools. In 1995, he cracked Baseball America’s Top 100 Prospects list at No. 85, hit .333/.383/.544 with 16 homers at Class A Albany and rose to No. 9 on BA’s list the next spring. After an even better season (.360/.431/.618 split between high A ball and Double A) in 1996, he joined the Expos, debuting on Sept. 19 by going 1-for-5 with a single off the Braves’ Steve Avery. Two days later, he hit his first major league homer off Mark Wohlers on a low-and-away fastball, several inches off the plate—a portent of things to come.

Ranked second on BA’s 1997 prospect list (behind the Braves’ Andruw Jones), Guerrero won the Expos’ starting rightfield job in spring training, but in late March, he fouled a ball off his left foot, suffering a fracture that delayed his season debut until May 3. Despite two other stints on the disabled list, he hit .302/.350/.483 in 90 games. Home cooking had to help: He brought his mother to Montreal to feed him, a move that would become a staple of his career. It helped having the widely respected Felipe Alou—at that point the career hits leader among Dominican-born players—as manager and fellow Dominican and reigning Cy Young winner Pedro Martinez as a mentor. Martinez wrote the address of his apartment down for Guerrero, in case he got lost in the big city.

Though the Expos were amid a five-year sub-.500 stretch and would lose 97 games in 1998—their most since '76—after trading Martinez to the Red Sox, Guerrero emerged as a star that season, batting .324/.371/.589 with 202 hits, including 38 homers (good for sixth in the league) and 7.4 WAR (fourth).

Hailed by Journal de Montreal baseball columnist Serge Touchette as “the first brick” to a proposed downtown ballpark to replace the outmoded Olympic Stadium, Guerrero signed a five-year, $28 million extension in September, setting a record for a player with less than two full years of major league experience. He more than lived up to it. From 1998 to 2002, he hit a combined .325/.391/.602 and averaged 196 hits, 39 homers, 22 steals and 5.9 WAR. Twice he placed third in the league in batting average (.345 in 2000, .336 in '02), and three times he ranked among the top five in homers, with a career high of 44 in '00—fourth behind Sammy Sosa (50), Barry Bonds (49) and Jeff Bagwell (47). He reached the 30–30 club for the first time in 2001, with 34 homers and 37 steals, and barely missed becoming just the third 40–40 player in '02, finishing with 39 homers and 40 steals. In that stellar season, he led the NL in hits (206) and total bases (364) and placed second in WAR, helping the Expos to 83 wins, their best showing since 1996. His 29.7 WAR over that five-year span ranked seventh in the majors, and his 151 OPS+ was tied for 12th. He made the NL All-Star team in the last four of those seasons.

Guerrero also gained renown for his unorthodox approach. “This guy went 80-something at bats without a strikeout,” Alou told Tom Verducci for a 2000 Sports Illustrated cover story. “But this guy swings from his ass. He’s not just trying to make contact. The guy is the strangest hitter I’ve ever seen. I don’t believe he truly knows what he wants to do yet. If he wants to hit 50 or 60 home runs, he can do it and hit .310. If he decides to bat .350, he can do that because he has outstanding bat control.”

Though productive in 2003 (.330/.426/.586 for a 156 OPS+ with 25 homers), Guerrero missed 45 games in midsummer due to a herniated disc in his lower back. The Expos, now managed by Frank Robinson, were 32–19 and leading the NL wild-card race when Guerrero went down but went 18–29 during a span in which he played just two games. The team finished with 83 wins and missed the playoffs.

Alas, by that point, funding for Montreal’s new ballpark had long since fallen through. In the winter of 2001–02, the Expos, whose attendance had languished below one million for four straight seasons, were considered for contraction as part of a ploy by the owners to put pressure on the players’ union as they negotiated a new Collective Bargaining Agreement. Ultimately, in early 2002, the team was sold to the other 29 major league teams, with owner Jeffrey Loria allowed to purchase the Marlins. In turn, Marlins owner John Henry would go on to purchase the Red Sox, and MLB would move the Expos to Washington, D.C. following the 2004 season.

Joe Morgan's Plea to Ban Steroid Users from the Hall of Fame is Simplistic and Reactionary

The Expos had almost no shot at retaining Guerrero once he reached free agency, though they did offer him a five-year, $75 million contract on July 24, 2003, a deal he rejected. Upon reaching free agency, he was heavily pursued by several teams: The Orioles offered him six years and $78 million, and the Mets put forth a deal of five years and $71 million, albeit structured as a three-year, $30 million guarantee plus incentives based upon playing time. The Dodgers bid five years and $70 million and believed they had a deal, but their sale by News Corp. to Frank McCourt stalled the contract. Ultimately, Guerrero signed a five-year, $70 million deal with the Angels; the contract included a $15 million club option for 2009.

The deal paid immediate dividends. The 29-year-old slugger hit .337/.391/.598 with 39 homers, 206 hits, a league-leading 366 total bases and 5.6 WAR in 2004. A blazing September (.363/.424/.726 with 11 homers) carried the Halos past the Athletics in the AL West race and secured Guerrero the MVP award. But despite his grand slam off Boston’s Mike Timlin in Game 3 of the Division Series, the Angels couldn’t avert a sweep.

While Guerrero couldn’t quite repeat the magic of his 2004 season, he helped the Angels to five first-place finishes in six years in Anaheim. From 2005 to '07, he hit a combined .324/.393/.554 and averaged 31 homers, 184 hits and 4.7 WAR. Thanks to an increasing amount of time at designated hitter, he was able to remain in the lineup, missing substantial time only due to a partial separation of his left shoulder (suffered in a headfirst dive into home plate), which cost him three weeks in 2005. His 2008 was a step down: Though he hit .303/.365/.521 with 27 homers, he battled right knee soreness (a problem in '06, as well) and other minor maladies. He played as the DH 44 times and finished with 2.5 WAR, his lowest mark since 1997. Guerrero wound up needing surgery to repair a torn meniscus in his right knee after the Angels were again ousted from the playoffs by the Red Sox, this time despite his 7-for-15 showing.

The Halos exercised their option on Guerrero despite the surgery, but neither he nor they could stop the march of time or his inadvertent slip in an interview, where he revealed he was 34 years old instead of 33. On April 2, during the team’s exhibition “Freeway Series” against the Dodgers, he tore his right pectoral muscle while making a throw from rightfield to third base. Between that injury and a right calf strain suffered on July 7 during just his second game afield, he played only 100 games and hit .295/.334/.460 with 15 homers.

Now more or less a full-time DH, Guerrero left Anaheim for the hitters’ haven of Texas and hit .300/.345/.496 with 29 homers for the Rangers. He earned All-Star honors for the ninth and final time and reached the World Series, a first for both him and the Rangers. In his first series at-bat, Guerrero doubled in a run off two-time Cy Young winner Tim Lincecum, but he went 0-for-13 the rest of the way as the Giants downed Texas.

After a forgettable season as the DH for the Orioles (.290/.317/.416 with 13 homers) in 2011, the going-on-37-year-old Guerrero couldn’t find a major league deal to his liking. In May, he finally signed with the Blue Jays, and after a couple of weeks in extended spring training, he homered four times in 12 games at two minor league stops. He opted out of his contract in mid-June, when the Blue Jays dragged their feet on recalling him, but couldn’t find another deal. After a brief Dominican Winter League stint, he put together a short video showing himself training in the Dominican, but the best he could muster was a contract with the Long Island Ducks of the independent Atlantic League. Family issues precluded his joining the team, however, and he finally announced his retirement in September 2013. (Because Guerrero last played in the majors in 2011, he became eligible for the '17 ballot.)

As for his Hall of Fame case, long story short: Guerrero did oodles of the things that Hall voters have traditionally rewarded. Despite last playing in the majors at age 36, his early start left him with healthy career totals of 2,590 hits and 449 homers, not to mention a .318 batting average, 36th among players with at least 7,000 plate appearances. Batting average isn’t everything, of course, but Hall voters have overwhelmingly rewarded such elite performances. Every eligible player who has hit at least .317 in at least 7,000 PA is enshrined except Guerrero with the still-active Miguel Cabrera (.318 through 2017) the only other player outside. How Guerrero accomplished such a mark given his liberal interpretation of the strike zone remains an astonishing feat.

Guerrero finished above .300 in 13 of his 15 full seasons. Between that and his other accomplishments—10 100-RBI seasons, nine All-Star appearances, six-30-homer seasons (plus two 40-homer seasons), six trips to the playoffs and four 200-hit seasons—his Hall of Fame Monitor score of 209 ranks 42nd among position players, significantly higher than the aforementioned ex-Expos (Larry Walker at 148 is the high). The only players above him who aren’t enshrined are either active (Cabrera, Albert Pujols, Ichiro Suzuki), waiting to hit the ballot (Derek Jeter, Alex Rodriguez), on the ballot alongside Guerrero (Manny Ramirez) or named Pete Rose or Barry Bonds.

Despite an aggressive approach that yielded a flimsy 6.5% walk rate, Guerrero’s power demanded the utmost respect. His 250 intentional walks (fifth-highest since the stat became official in 1955) helped pushed his on-base percentage above .400 four times, but relative to his high batting average, his .379 OBP is a bit light. At the 7,000 PA level, Guerrero’s 140 OPS+ is in a virtual tie for 47th with A-Rod, Gary Sheffield, Duke Snider and Jesse Burkett. There are only 16 players outside the Hall at that level or higher in that much playing time; seven besides Guerrero (Bonds, Edgar Martinez, Ramirez, Sheffield, Walker and newcomers Chipper Jones and Jim Thome) are on the ballot, one (Mark McGwire) was a Today’s Game Era Committee candidate last year, and three more (Rodriguez, Lance Berkman and David Ortiz) will become eligible in the next five years. Two more (Pujols and Cabrera) remain active. The other two besides Guerrero are frequent Veterans Committee/Golden Era candidate Dick Allen and the forgotten-except-in-folkore Frank Howard; “The Capital Punisher” hit 382 homers but accumulated just 1,774 hits, essentially ruling him out from Hall consideration.

Guerrero’s advanced-stats case isn’t as strong. His 59.3 WAR ranks just 21st among rightfielders, 13 wins shy of the standard and ahead of just 11 of 24 enshrined players, of whom only Wee Willie Keeler was voted in by the writers. His 41.1 peak WAR ranks 18th all time, about two wins shy of the standard and ahead of 12 of 24 Hall of Famers; he's tied with Tony Gwynn. Guerrero's 50.2 JAWS is 21st at the position, eight points off the pace and again ahead of 11 of 24 enshrined. Among current ballot rightfielders, he’s well below Walker (58.6) and only slightly above Sheffield (49.2)—two whom the voters have barely noticed thus far.

That Guerrero is so far below the JAWS standard a bit of a surprise. His position puts him among the likes of Babe Ruth, Hank Aaron, Stan Musial, Frank Robinson and Mel Ott—all of whom have at least 100 WAR—has the highest standard (58.1) of any. Still, only at catcher (where players are constrained by playing time) is the Hall standard below 50.2 JAWS. It’s not Guerrero’s offense that clamps his JAWS: He’s 11th among rightfielders in Batting Runs (429), second among those outside the Hall behind Sheffield (561). He cost himself 20 runs via baserunning and double plays; while he stole 181 bases, his 65.8% success rate was subpar, and he’s tied for 18th in double plays grounded into (since 1939, when the stat became official) with 277.

Chipper Jones, Jim Thome Join a Bulky 2018 Hall of Fame Ballot

Defensively, while Guerrero had a powerful arm via which he led the league’s rightfielders in assists three times and finished among the top four nine times, he also led in errors nine times, including seven years in a row from 1997 to 2003. His range was nothing special: He was below average in chances per nine innings in five of the 12 seasons that he played the outfield regularly while playing behind pitching staffs that were slightly more fly-ball-oriented than the rest of the league. He was actually 29 runs above average through 2003 according to Total Zone but 22 runs below average from '04 onward, when Defensive Runs Saved became the basis of fielding runs and when he was slowing down with age and injuries.

What’s more, the second half of Guerrero's career includes 508 games at DH, which further cuts into his value. His defensive WAR—the combined value of his fielding runs and his positional adjustment—for his career is -10.7. WAR estimates that the value of playing a full season in rightfield is -7 runs, compared to -15 at DH and +2 at third base; Guerrero thus has a lower dWAR than Edgar Martinez (-9.7), who played roughly as many games at the hot corner as Vlad did at DH.

His -10.7 dWAR is the 17th-lowest among the 43 rightfielders with at least 7,000 PA, with only five Hall of Famers below him: Dave Winfield (-23.7), Sam Crawford (-18.1), Reggie Jackson (-17.2), Harry Heilmann (-14.0) and Chuck Klein (-11.9). Winfield and Jackson have milestone totals that virtually guaranteed their elections. Guerrero does not, nor does he have the hook of being a great postseason performer (.263/.324/.339 with two homers in 188 postseason PA).

When Guerrero became eligible last year, the question was the extent to which the crowd atop the ballot—Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines and Trevor Hoffman all received at least 67% of the 2016 vote—and the voters’ rough treatment of other greats from the Expos’ diaspora would work against him. After all, while Pedro Martinez and Randy Johnson were both first-ballot honorees thanks to their collections of Cy Young awards, BBWAA voters made Gary Carter—who ranks second at the catcher position in JAWS, made 11 All-Star teams (seven as a starter) and won a World Series with the Mets—wait six years for election. Andre Dawson, a former MVP and eight-time All-Star who finished with more hits and a similar number of homers to Guerrero, took nine years. Raines, who ranks eighth among leftfielders in JAWS, was elected in his 10th and final year of eligibility. Walker, another former MVP and the 10th-ranked rightfielder in JAWS, hasn’t cleared 25% of the vote through seven years of eligibility. Even with those players’ subsequent moves to major media markets, the Expos’ lack of stateside exposure during their tenures probably worked against them.

That wasn’t the case for Guerrero, who fell 15 votes short of election on 2017, receiving 71.7%. Not only is he the closest first-year near-miss since Roberto Alomar received 73.7% in 2010, those two are the only ones in the history of the BBWAA vote—all the way back to 1936—who debuted with at least 70% but fell short of 75%. Alomar was elected in the following year, and in fact, since the voters returned to annual balloting in 1966, the same goes for 16 of the other 17 candidates with between 70-75%. The exception was Jim Bunning, who fell short in both his 11th and 12th years of eligibility (with 70.0% and 74.2%, respectively), then receded in years 13-15 and was ultimately elected by the Veterans Committee.

Guerrero won’t suffer that fate. To what was already a compelling mix of traditional stats and accolades and a certain aesthetic charm borne of his electrifying style, he’s got voting history on his side. He may not have the JAWS stamp of his approval—or a spot on my virtual ballot, which is guided by my metric—but I loved watching him play. He made the hair on the back of my neck stand up, and I won’t complain in the least when he’s elected.