There Is Something About Football

This story appears in the Oct. 9, 2017, issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

A man has come home to learn about football. He stands on a sideline, watching high school boys play a game in the bright sunshine of a Saturday afternoon in the part of upstate New York that is closer to Canada than it is to New York City, so close to Vermont that you can walk there. It has been almost five decades since the Man was last on this field, yet it seems little has changed. The smell of cut grass mixing with sweat. The competing sounds of referees’ whistles, adolescent cheerleader chants and angry rebukes from beyond the fence line. Pads flapping as players run past. A distant, creeping sensation of fear. The Man has witnessed hundreds of practices and games, yet in this place the familiar becomes poignant. Because there is something about football.

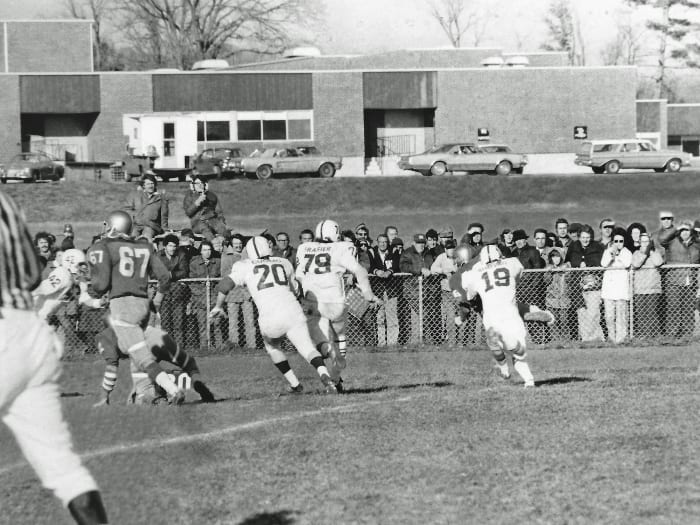

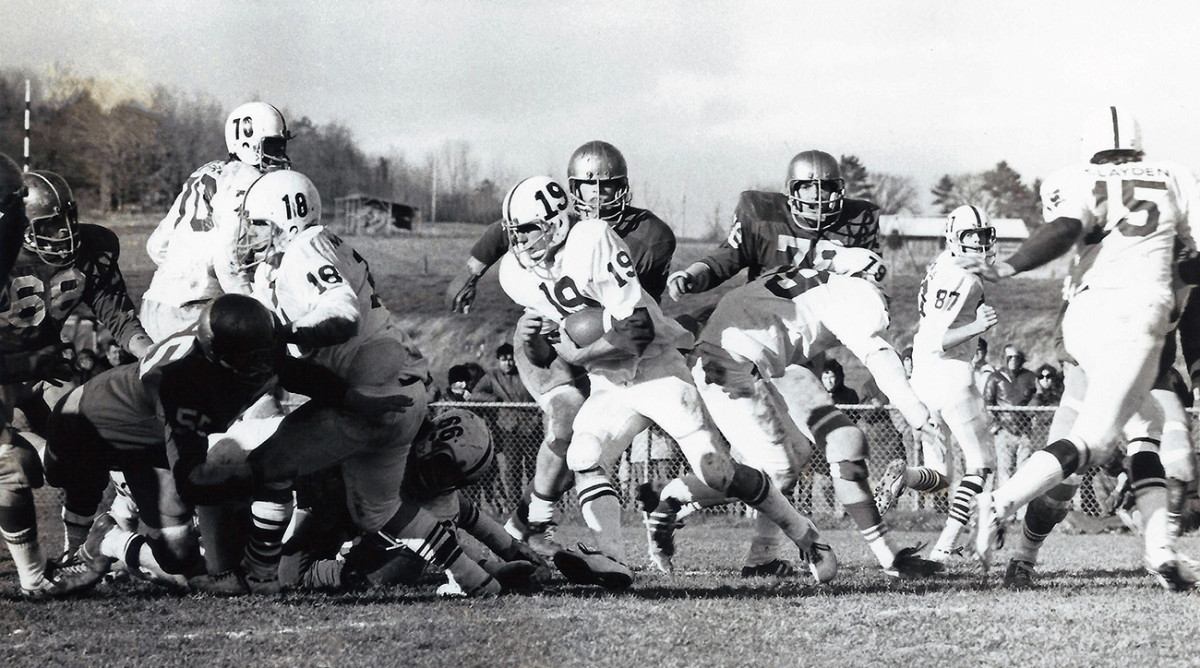

He last stood on this sideline on the first Saturday in November 1973. His team, Whitehall, defeated Granville, a longtime rival, 11–0 that day, completing an unbeaten eight-game campaign that was saved from a postseason blemish because there was no postseason. Memories are sparse and hazy. It was cold and very windy. The Man played quarterback and kicked a very short field goal. There was a party that night, but he was an altar boy and had to serve the Saturday-night vigil mass, unbeaten season or not—that part the Man remembers vividly. The rest is mostly lost to the fog of time.

All these years later, there is so much uncertainty about football. It is demonstrably unsafe at its highest level and very much in some sort of crisis down to its roots. Professional players are retiring in their 20s. Parents are debating whether to expose their children to the sport’s risks. Participation is down, but not everywhere. The politics of America in 2017 have driven a wedge into the game. The sport remains our televised and wagered-upon passion, yet a steady erosion of trust suggests that in the future, the game will look very different. Maybe that future is 10 years away. Maybe 50. But change is in the air.

The Man’s experience was hardly different from that of tens of thousands of others, years older and years younger. Only the biggest, fastest and strongest will play college ball, and a smaller subset of genetic outliers will play in Division I. Far fewer still will reach the NFL. The vast majority of former football players are those who competed on their high school teams, and this is the way in which participation becomes a kind of connective tissue across the decades. The game they played is scarcely related to the game they watch on TV now, yet this thinly shared experience makes them a critical part of the sport’s fan base and its institutional memory.

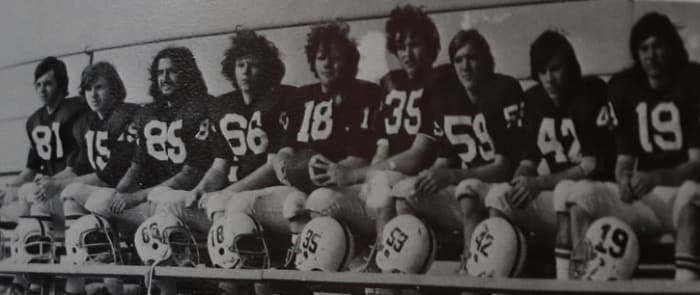

There were nine senior starters on the Man’s last high school team, back in 1973. None of them were great players, but they were the best in one very small town that cared as deeply about the sport as just about anyplace in Pennsylvania or Texas or Florida. In all of those 44 years the Man had barely spoken to any of them, but he will seek them out now and ask about football and life. He will try to understand not only what keeps the game alive, but what might be lost if football is someday gone, especially in hundreds of small towns across America. Towns like theirs.

He finds one—and only one—classmate still living in Whitehall. Four others live in upstate New York, within 90 minutes of their childhood homes. One lives in Arkansas, another in California and another in Pennsylvania. The eight of them have a total of nine children (just one boy) and nine grandchildren. Three have had heart surgeries, one has had both knees replaced. Two served in the military. Four have earned college degrees. One is retired, another semi-retired. Some have lived tougher lives than others. One overcame a cocaine addiction that nearly killed him. All of them pay attention to football, but only a couple are fanatical about it. They all have memories about the sport they hold close.

First, though, some history.

The village of Whitehall, settled in 1759 by British army captain Philip Skene and initially called Skenesborough, lies 250 miles north of New York City in a narrow valley between small ranges of the Adirondack Mountains to the west and the Green Mountains to the east. Of greater historical significance, it’s also at the northern terminus of the Champlain Canal, a 60-mile waterway that connects the Hudson River to the southern end of Lake Champlain. The setting is idyllic, although the village hasn’t been described in such terms for a long time.

A child growing up in Whitehall would learn (and any traveler passing through on the way to Canada or slicing across into Vermont would read, on a sign or in a museum) that Whitehall calls itself “the birthplace of the U.S. Navy.” That assertion is befuddling to many because 1) landlocked Whitehall is hundreds of miles from the nearest ocean and 2) Philadelphia, Providence and the Massachusetts towns of Marblehead and Beverly have made the same claim. What is not in dispute is that in the summer of 1776, after Skenesborough was captured by American forces, a fleet of ships assembled in the town’s harbor, sailed north under Benedict Arnold and engaged the British in the Battle of Valcour Island on Lake Champlain, among the earliest actions by any American maritime force. (The Navy chooses to punt on this issue, stating, “Perhaps it would be historically accurate to say that America’s Navy had many ‘birthplaces.’ ”)

Whitehall thrived in the 19th century and through much of the 20th, first with shipbuilding and then with mills along the canal and as a key railroad center between New York and Canada. The town still has a monument to its veterans in a canalside park downtown. Dozens of boys who came of age in Whitehall in the 1960s were drafted or enlisted to serve in Vietnam. Several were killed in action, including the 20-year-old son of a decorated World War II veteran. But the teenagers who would play football in the ’70s were largely spared Vietnam and the roiling national unrest that accompanied it. For them, Whitehall was a nurturing small town, homogenous and blue-collar, and in many ways still tethered to the relative simplicity of post–World War II America.

The town’s population in those days hovered around 4,000; graduating classes numbered on either side of 100 students. The downtown was vibrant, with one of every kind of store—clothing, hardware, jewelry, pharmacy—plus four grocers. In truth, though, Whitehall was already slowly dying. The mills were gone by then, and the railroad was on the way out. (Whitehall High would change its nickname in 1986 from the soulless Maroons to the organic Railroaders, a logical shift that was actually decades too late.) Construction of a major highway from Albany to Montreal that was completed in the ’60s and that bypassed Whitehall was proving a crushing blow. The village’s population peaked at 5,258 in ’20 and had fallen to 3,764 by ’70.

But there was football. A young boy growing up in Whitehall in the 1960s and ’70s would hear endless stories of the town’s gridiron tradition. He would hear about a legendary coach named Ambrose (Gilly) Gilligan, who still lived in town and by then was in his 70s and bald, but who retained a palpable presence. Whitehall began playing football in 1913; Gilly took over the program in ’26 and peaked during a four-year run, from ’38 through ’41, that included an unbeaten, unscored-upon season in ’39. In November ’41, Look magazine, a national photo-driven weekly with immense influence, featured a five-page spread on “the football-crazy town of Whitehall.” (That issue was published 19 days before the attack on Pearl Harbor, and many of the boys pictured would be in uniform within months.)

Whitehall’s performance waxed and waned through the 1950s and ’60s, but a reputation for toughness and a certain type of physical abandon lingered. Even today’s coach, 45-year-old Rich Gould, refers to his roster as having “a few Whitehall-type players—tough kids.”

In 1966, Whitehall named 33-year-old John Millett as its coach, and a year later 52-year-old Gordon Foote joined as his top assistant. Together they would be the twin beating hearts of the program for two decades, memorable figures in the lives and memories of the teenagers who played for them. Both men were Whitehall natives. Millett’s father had been on that first Whitehall football team in ’13, and Millett himself was a star Maroons running back in the late ’40s before he did a hitch in the Marines. Foote had played for Gilligan in the early ’30s and was a decorated World War II vet—twice wounded, once in the belly by machine gun fire.

They were a terrific match, both different and alike. Millett was a tactician: His hybrid T-formation offense, with its unbalanced line, terrorized foes with power running and sprint-out passing. Foote was a lover of poetry and opera who wore a small, neat bow tie in the classroom—but he was all blood-and-guts on the football field. More than one of his old charges can remember hearing his baritone instructing some downed player, “Get up! I’ll tell you when you’re hurt!” Millett was a hunter, and also a driver’s-ed teacher, and there’s an old story that he would bring his deer rifle along on class rides into the country-side, just in case he saw something worth taking down. That story isn’t true, but it gets to the heart of how he is remembered. Foote was a professional rattlesnake hunter. “After World War II, he rarely found anything that could match the adrenaline of that experience,” says his daughter, Sally Douglas. “Until he started hunting snakes.”

Together Millett and Foote restored legitimacy to a program that had enjoyed just two winning seasons in a decade. Kids in town began flocking to games again; high school players were heroes as much as were NFL players. (One of their first stars was Al Fredette, Jimmer’s dad.) In the coaches’ fourth season together, in 1970, Whitehall went 8–0 and defeated Granville, which also was unbeaten, 32–7 in the final game of the year. Newspapers reported that 5,000-plus people attended that game, more than the population of either town. (In legend, attendance has risen beyond 10,000.)

The Man and his buddies were freshmen that fall. One of them played a few snaps against Granville. The others waited for a chance to play in such a game, someday, wearing maroon-and-white.

The man’s mother, gone three years now, kept a scrapbook. When the Man and his brother and sister eventually cleaned out the family house, the book was sitting on a basement shelf, beaten but readable. From that 1973 season it depicts eight games and eight victories, only two of which were close. It was, in truth, a relatively easy 8–0. Whitehall scored 249 points, gave up only 91 and finished ranked No. 2 among New York State’s small schools, a piece of suspicious voting by sportswriters who couldn’t have had any idea how a team from Whitehall might compare with a team from, say, Binghamton. Still, it sounds very impressive. (One year later, New York would commence the beginnings of what has become a multi-class state tournament. Just one other Whitehall team since, in ’77, has finished unbeaten.)

It is important here to put the institution of football into historical perspective. In 1973 the game was unambiguously celebrated. Monday Night Football had launched in ’70 and was a national phenomenon. The Dolphins went unbeaten in ’72, and O.J. Simpson ran for 2,000 yards in ’73. There was John Madden, coach of the Raiders, but there was no Madden; fantasy football was still in its infancy.

There was little discussion of player safety. At all levels, concussions were something to be shaken off; players took pride in the war marks on their helmets. It was in his seminal 1927 book, Football for Coaches and Players, that Pop Warner wrote, “Football requires and develops courage, co-operation, loyalty, obedience and self-sacrifice. It develops cool-headedness under stress; it promotes clean living and habits.” This kind of thinking had changed little in four decades.

This is the world in which nine seniors played for Whitehall in the fall of 1973. They remember little of scores, statistics or rankings. (They all, however, remember the score of the Granville game.) They remember friendships and family. And moments. Nine seniors, old men now, football far in their past, mortality a daily presence. Nine men, nine stories.

From left to right: #87 Marc Nichols, #15 Tim Layden, #85 Jim McKee, #66 Steve Toben, #18 Marty Gordon, #35 Bill Greco, #59 Tim Nichols, #42 Ray Greenwood, #19 Bob Shovah

Courtesy of Ray Greenwood

#18, MARTY GORDON

A 5' 7", 215-pound running back and linebacker, Marty was thick and strong, with curly red hair and shockingly quick feet, a grown man at 14 and a nightmare for undersized, small-town defensive backs. He was the only member of the 1973 team to play all four years on the varsity, and he was one of eight children who lived in a small two-bedroom house next to a bridge over the canal. His father worked a grueling job in the boiler room at a folding-furniture factory in Granville; his mother made dinners for the team.

AFTER WHITEHALL: “I was not prepared to play college football,” says Gordon, 62, who spent one year on the freshman team at Norwich (Vt.) University. “It was a big step up, and I was not ready.” He stayed at Norwich, graduated with a degree in physical education and then did 20 years in the U.S. Army, retiring early as a major following the first gulf war. He has manned the pro desk at a Queensbury, N.Y., Home Depot, working with contractors, for the last 14 years.

GORDON: “The whole town was behind us, and I needed all the recognition and support I could get. I wasn’t book smart and I didn’t study. It was nice to win, but we were tight, I remember that. You [the Man] and I didn’t hang out in school, but we were brothers on the field. That team concept helped me in the military. . . . In school they taught us to tackle by aiming with the crown of the helmet; that doesn’t happen now. . . . Hey, you remember that swing pass we had? I had such a hard time catching that thing—couldn’t get my head around. But then you threw it to me in Corinth [Week 6, a night game], and it went for a touchdown. That was fun.”

#35, BILL GRECO

The best athlete and football player on the team—a 6' 3", 225-pound running back and linebacker—he was also an excellent basketball player and state-level discus thrower. As so often happens with the best players, Bill was selfless but also demanding of his teammates. His father, a tall, serious man, was one of the many Whitehall dads who worked as corrections officers at Great Meadow Correctional Facility, the cheerily named maximum security prison seven miles away in Comstock, N.Y. Great Meadow harbored serious, violent offenders. The men who worked there had an edge to them 24/7, as if it was difficult to leave work behind.

AFTER WHITEHALL: Recruited to D-III Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., Greco started at tight end his freshman year, then quit altogether. “I was drinking heavily and I almost flunked out,” he says. “So I quit and went to the library, and my grades went up. It was probably more the drinking than the football, honestly.” Greco, now 61, graduated with a computer science degree and has spent his career working as an IT specialist. In 2013 he experienced severe chest pains on a morning walk and thought to himself, Maybe this is it. Quadruple-bypass surgery has kept him going.

GRECO: “Football was the sport that taught me to be a we person more than an I person. That’s been helpful in building teams professionally. I wish I’d stayed with the game in college; I quit too early and I missed out on having those friendships like I had in high school. . . . All the talk about concussions now—I got one in the Cambridge game [Week 2]. You had to call a timeout and walk me over to the sideline. I didn’t know where I was.”

#42, RAY GREENWOOD

A 5' 10", 170-pound tight end and linebacker—one of two boys who shuffled calls in from the sideline—Ray played with one bad wheel, the result of knee cartilage torn as a sophomore plus the primitive clean-out surgery that followed. (He broke his left arm on the same play, which cannot have happened often.)

AFTER WHITEHALL: Greenwood, too, graduated from Union College with a computer science degree, and worked 20 years for a Minneapolis tech outfit before following his wife to Australia, and then to California, where he worked in disaster relief with the Red Cross, including during Hurricane Katrina. At 60 he’s a consultant in emergency management. He has had both knees replaced and underwent a mitral-valve repair on his heart.

GREENWOOD:“Football’s not a defining thing in my life, but the team concept has carried over into other things. [At Whitehall] we had kids who wanted to go to good colleges and kids who wanted to be prison guards or farmers—but we got along. . . . Do you remember the Queensbury game [Week 7]? You threw me a touchdown pass. It was the only one I ever caught. I was completely wide open and all I could think was, I’m going to drop this.” (Greco: “He juggled it a few times.”)

#85, JIM MCKEE

The team was relatively short on nicknames, but Jim, a defensive tackle, was known almost since birth as Moose, and that stuck despite his being only 6 feet, 165 pounds. In pictures he looks half a decade older than the rest of the team: full black beard, hair to his shoulders. He was one of eight kids—“Back then if you didn’t have at least four or five, you weren’t trying, right?”—and his father, a Whitehall native, was also a corrections officer.

AFTER WHITEHALL: Hired to work on the railroad at 19, he learned welding from an older guy and spent 30 years helping secure track from Albany to Montreal. (“Continuous welds,” he says. “You ride that train, you won’t hear that clack-clack-clack because the welds are so good.”) McKee retired at 50 and today, at 61, is the only one of the nine seniors from 1973 who still lives in Whitehall, in a house on Third Avenue. His grandson Dawson Procella is a senior on this year’s Railroaders, a lanky, 6' 3" receiver.

MCKEE:“Football was a big deal back then in Whitehall. . . . Billy Greco and Marty Gordon were the linebackers, and they were way bigger than I was. They hit me harder than most of the guys on the other teams.”

#87, MARC NICHOLS

The Man threw a few dozen touchdown passes in four years of football, and Marc caught the majority of them. He was 6' 2", 165 pounds and ran with a loping stride that looked slow but wasn’t. Of all the seniors, he was the only one named to any kind of all-star team, a very big deal in those days. Marc’s dad had died three days before his 12th birthday, taken by a cerebral hemorrhage while working on the railroad in the Adirondacks.

AFTER WHITEHALL: Nichols, 62, is retired following two careers with the New York Department of Corrections, first as a corrections officer and later as a counselor. In between, in his mid-30s, he fought a cocaine addiction. “I almost destroyed my life,” he says. “I was one day away from the streets when I sought help. God gave me another chance.” He married at 51 and in 2012 moved to a retirement community in Arkansas. He’s a rabid Alabama football fan and makes at least one trip every year to Tuscaloosa.

NICHOLS: “One game you threw me a pass, and it was cold and it skipped off my fingers and it really hurt. I ran off the field yelling for the coaches to put somebody else in, and Coach Foote shoved me right back out there. . . . I wish my father could have seen me play. My mom and my sisters were there for every game—but, you know, it’s your dad. . . .”

#59, TIM NICHOLS

The other tight end/linebacker who shared time and play-messengering duties with Ray Greenwood, Tim (Marc’s cousin) was skinny as a dry reed at 6 feet, 146 pounds, but he was a vicious tackler. His father, a Whitehall native, worked in a nearby chemical plant and was chief of the local volunteer fire department.

AFTER WHITEHALL: Nichols served 17 years in the Air Force, then worked six as a commercial airline mechanic and 18 as a conductor for the Canadian-Pacific Railroad in upstate New York. At 62 he’s married with a daughter who just started college.

NICHOLS: “I loved the game. I loved the hitting. I don’t remember being told to lead with the head. They told us to tuck the head in, I think. . . . In the Granville game, Billy Greco and I hit a guy and cracked a vertebrae in his back. . . . I follow the Giants now. I still love football. I really love it.”

#19, BOB SHOVAH

Every high school team needs a fast running back. Bob was that guy: 5' 9", 174 pounds, with open-field speed. (He was also a defensive back and left-footed punter.) Taken in at birth by an aunt and uncle, his adopted father died when Bob was a Whitehall freshman. The day before graduation, he delivered an invitation to his birth father. Did he attend? “Nope.” Bob still hasn’t seen him.

AFTER WHITEHALL: Married 36 years now, with three children and four grandchildren, Shovah worked in the paper mills for nearly two decades, ran a girls’ softball league in nearby Fort Edward for 14 years and today is a construction laborer. After having quintuple-bypass surgery nine years ago, he says, at age 63, “I feel like a 35-year-old. I’ve got no complaints, man.”

SHOVAH: “[That team] was so much fun. We had no distractions, no phones or video games. It was just football, and we were serious about it. . . . I remember the Fort Edward game our senior year [Week 5]. I ran a sweep and raked my hand on a piece of glass on the field. I got back to the huddle and somebody said, ‘You might want to get that looked at.’ I looked down and there was blood all over my white pants. I went to the hospital, missed the rest of the game. I’ve still got the scar.”

#66, STEVE TOBEN

A classic Whitehall lineman—5' 11", 147 pounds and lots of fury—Steve was a fourth-generation Whitehall boy. His grandfather Clayton grew up with Coach Foote, so Foote always addressed Steve as “Clayt.” Steve’s dad was an electrical engineer for the railroad, and he would sometimes take his son on the weekends to work, where Steve would drive the locomotive a few miles down the track from the big roundhouse in Whitehall. Steve raced snowmobiles in the winter.

AFTER WHITEHALL: Having graduated from Clarkson University (in Potsdam, N.Y.) with an engineering degree, Toben has worked his adult life as an engineer and manufacturing manager and now lives in northwest Maryland, where he has Ravens season tickets. (After the protests of Sept. 24 he said he is considering getting rid of them.) His wife, a neuropsychologist, has studied brain injuries in football players. “I love the NFL games,” he says, “but you wonder sometimes how they survive those hits.”

TOBEN: “The St. Mary’s game—they’d beaten us as freshmen, and we really wanted to win that game. They had a big running back, and I remember hitting him all day, and it just beat the tar out of me. What a long day. But we won. And then Granville. My dad wore a sport coat to that game and met me in the end zone to shake my hand.”

Former football players are relevant to the ongoing popularity of their sport not because they played well or because they played poorly, but because they played at all. The records show that in the fall of 1973, I threw 13 touchdown passes and 10 interceptions—hideous inefficiency. Years later I played catch with Chargers quarterback Philip Rivers for a story in Sports Illustrated. I prided myself on throwing tight spirals and began upping the intensity until Rivers returned fire with such velocity that I tipped my head to the side before catching each ball, fearing it might tear through my hands and hit me in the face. There is no physical correlation between them and us.

I was one of only four Whitehall seniors who didn’t play on both offense and defense, because my fragile 6-foot, 170-pound body, better suited to basketball and -middle-distance running, was already breaking down at age 17. (Still, I was stubborn enough to play a year on the freshman team at D‑III Williams College, where my mediocrity was further exposed. I’ve since had neck surgery and will soon be getting a knee replaced; eventually, I’ll have the other one done too.) But I’m much the same as my old teammates: Random moments bubble to the surface and bring a smile or a tear. The experience is measured by those pearls more than by achievements or plaudits.

In my junior year I was the backup quarterback, and in the second game of the season the starter was having a rough day. I was inserted to complete a basic sideline pattern. Nervous to the point of blurred vision, I short-armed a throw that was intercepted and run back nearly for a touchdown, sealing our defeat that day and ruining the seniors’ year before the leaves began falling. I returned to the bench, and one of my friends asked if I’d bet on our -opponent—it sure looked like it. I was crestfallen, but afterward a senior -teammate—the receiver for whom my ill-fated- pass had been -intended—sat down next to me in the locker room, put his hand on my back and promised that things would get better. It was my first real exposure to the meaning of teammates. Things did get better. (The boy who comforted me died in 2001; he was 46.)

Months later, in the summer before the 1973 season, seven of us seniors drove 90 minutes south to Albany, where my uncle Joe operated a sporting goods store. We all bought white cleats that we’d reserve strictly for games—a very bold fashion statement in that era. I was proud to bring all my buddies and get them outfitted. “White shoes,” Ray Greenwood says today, laughing about the memory. “We must have thought we were so cool.”

And the parents. They truly loved it all more than we did, a phenomenon I wouldn’t understand until my own two kids played sports or took on other things at which they could publicly succeed or fail. My father was a lawyer; he and his brother handled real estate closings and wills for most of the families in Whitehall, but they also built a successful practice representing major corporations with factories or offices in the area. (We were the wealthy ones in town, even if it wasn’t real wealth.) My dad had served in the Navy in World War II and then played football at Union College on the GI Bill. He was a New York Giants fan and took me to several games in the old Yankee Stadium. He loved to tell me how Y.A. Tittle would pull the ball out of his running back’s belly on fourth-and-one and then throw deep to Del Shofner. Late in my senior season I pulled the ball out of Marty Gordon’s belly, without telling him or anybody else I was going to do it, and ran alone for a touchdown under the dim lights at Corinth, our only night game. My father loved that play, and I loved that he loved it. It’s my favorite personal sports moment for that reason alone.

In 1991, long after I was gone, Whitehall canceled its football season after just four games, beset by injuries and dwindling numbers. By then my parents had moved to a home that overlooked the football field from a distant hillside. In the evenings they could see and hear practices. When that season was called off, my mother sent me a note and a newspaper clipping with all the details. “Hard to believe, Whitehall without football,” she wrote in her pristine Catholic-school cursive. “I look out the kitchen window, and, no practice. I miss seeing the kids down there.”

My mother died 23 years later; we had a viewing at a -funeral home near Albany. Before the prayer service the priest approached me, holding a missal against his chest, and asked, “Did you play quarterback for Whitehall?” I was gobsmacked. It turned out he’d been a linebacker for Cambridge; we played each other four times. We shared a long handshake and a short, quiet laugh, football memories providing a soothing moment on a terrible night.

Time has been hard on the village. The population has fallen steadily for nearly a century, down to 2,614 in the 2010 census and estimated at slightly less than that today. The most recent high school graduating class was just 52 students. (My class graduated 94.) Unlike many communities in upstate New York and Vermont, Whitehall failed to refashion itself as a tourist destination for skiers and foliage watchers. It was left behind. Broadway and Williams Street, two of the busiest thoroughfares, are now lined with a succession of dilapidated houses, many of them former single-family residences carved up into apartments and left to rot. The once quaint and vibrant downtown, where my father kept his law office, has been gutted. Thirty percent of the town’s residents now live below the poverty level, more than double the national average of 14.9%. “It’s depressed,” says Jim McKee, the lone senior to stick around Whitehall. “No other way to say it.”

There is, meanwhile, a new golf course and health club, and the canal-side eatery that serves boats at the Lock 12 entry to Lake Champlain is under new ownership. School officials say class-size numbers are stable into the lower grades, and 50-year-old Whitehall High (with an addition in 2006) is pristine and appears much younger. Classrooms have whiteboards, and every student has a laptop. So there is hope. But it’s a long climb back.

Predictably, football—a sport of numbers—has been tossed about in all of this demographic shifting. The Railroaders started this year’s fall practice with 30 players in uniform, and that was the entire population of the program, grades nine through 12. (The good news: They began this summer with only 23 kids and slowly ticked upward.) Whitehall now competes in the smallest classification against the smallest schools. (Granville has held its population better, hence the two teams did not meet for a decade; the rivalry was resumed just last year.) But the problem is not just a shrinking population—it’s also a changing population. Most of the fathers and mothers of the seniors (and sophomores and juniors) on my high school team were born in Whitehall. Most of their grandparents, too. “For many years, when you played football at Whitehall, it was a family thing,” says 71-year-old Bob Prenevost, who taught at Whitehall High for 25 years and coached the football team from 2000 through ’07. “Your grandfather and your father played here. Your uncle played here. Now people move away.”

It’s true. One of the best players on my senior-year team was Mike Terry, a 6' 1", 180-pound sophomore lineman with a mean streak. (“Whitehall football taught me to be a man,” he says.) My father had been a groomsman in Mike’s dad’s wedding a -quarter-century- earlier. When Mike graduated, he left Whitehall and moved to Queensbury, a growing town 30 miles away, a place with more industry and recreation, within driving distance of state government jobs in Albany. His two boys played football there, and the youngest, Adam, grew to 6' 8", 330 pounds and played five years in the NFL. Al and Kay Fredette moved to Glens Falls, where Jimmer was not only a basketball star but also a wide receiver who was recruited by D‑I schools.

Gould, Whitehall’s current coach, played for the Railroaders in the late 1980s. “All the guys I played with left Whitehall,” he says. “There’s nothing to keep a middle-class family in town. If I had it to do over again, I might have left too.”

It’s not just about families and personnel. Two decades ago Whitehall had at least two dozen working farms, and farm boys tend to be hellacious football players. There are fewer farms now. Specialization, a nationwide issue, can be deadly where numbers are critical. The quarterback Gould planned to start this -season—whom he groomed last year—decided- instead to concentrate on baseball alone. And, of course, there are concussion fears. “I think we do a good job with player safety,” says Keith Redmond, who played for Whitehall in the 1980s and now is the school’s athletic director. “But if we lose one or two families, it’s disastrous.”

Through all of this, somehow a tradition endures and breathes some life into the village. Whitehall has reached the sectional championship game three consecutive seasons and even made the state quarterfinals in 2015. And a connection remains. “We hear the stories, the history,” says senior lineman Andrew Genier. “The rivalry with Granville, the big crowds and smashmouth football. That’s Whitehall.” Phelony West, a senior defensive back and receiver, says he grew up dreaming of wearing the maroon-and-white. Linebacker Brandon Bolster, a four-year varsity player, goes further: “You tell people around here you play football for Whitehall, that means something,” he says. “People—40, 50, 60 years old—tell you stories. It’s not just the past. It’s the present.”

On the night of Friday, Sept. 22, there is a milelong homecoming parade, starting at Putor-ti’s convenience store on Broadway and ending at the recreation center on Williams Street. Little kids wearing maroon flag football jerseys reach up to shake hands with varsity players riding on a flatbed. “This is one place the community comes together,” says 63-year-old Keith Whiting, a good football player in the class before mine who married his high school sweetheart and who has spent his entire life in the village. The parade ends with a giant bonfire, tall flames licking the night sky as cheerleaders and football players perform skits and dances. Allow yourself a moment of reverie and it might be 1941 again, with Look magazine taking pictures.

The next afternoon, under a blazing early-autumn sun, unbeaten Whitehall is trounced 50–0 by defending state champion Cambridge, a small-school powerhouse. Most of the several hundred people who attended the parade and bonfire are at the game, staying nearly to the end. From the sideline of his distant youth the Man thinks: It’s true that football will change, and someday perhaps be gone altogether. Justifiably so. Yet it is inescapable that here the game stubbornly endures while the town around it slowly dies. There is something about football.

On the field, young boys play as the warm sun falls, racing toward another game on another weekend.